Max Fridman is one of the three essential series in Vittorio Giardino’s opus. Sam Pezzo, Max Fridman, and Jonas Fink are the series that mark his evolution from the hard-boiled genre towards historically complex narratives. The first series is set in the 1970s, the second in the late 1930s, and the third in the 1950s. Sam Pezzo, a comic noir, a detective series, is done with a black and white technique, with more black than white, somewhat resembling the chiaroscuro of Alack Sinner by Carlos Sampayo and José Muñoz. But with a much stricter drawing style that has no intention of deconstructing its graphic form. Furthermore, after Sam Pezzo, Giardino will move in the opposite direction from playing with darkness, towards the “clear line” and color.

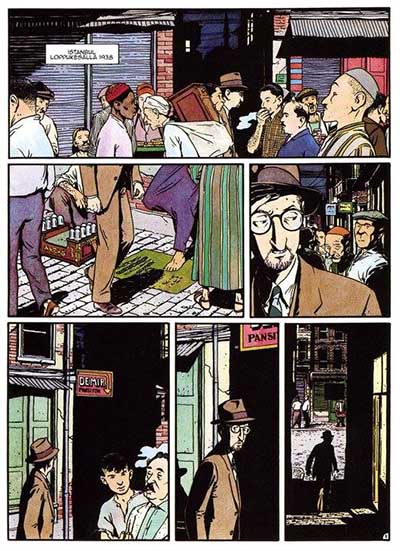

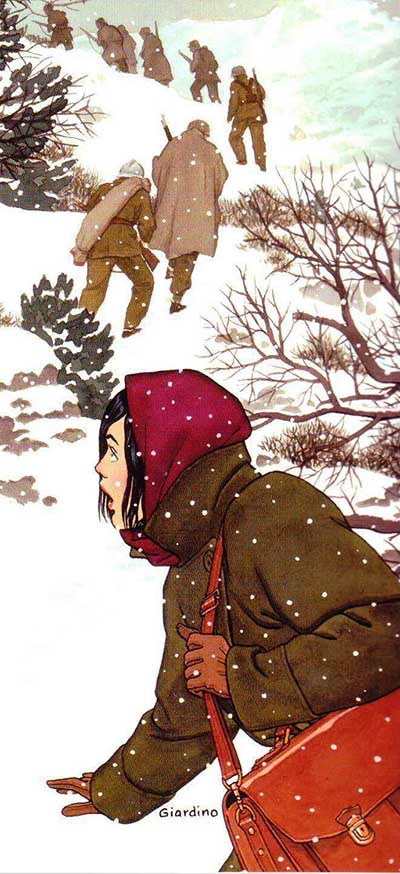

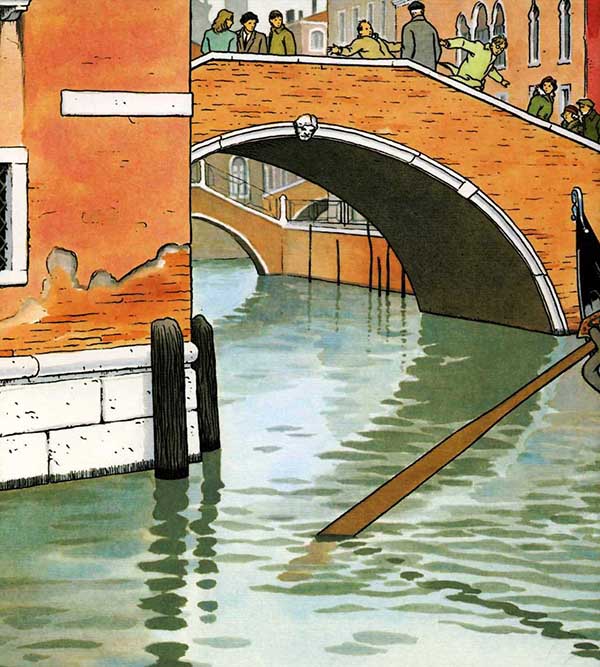

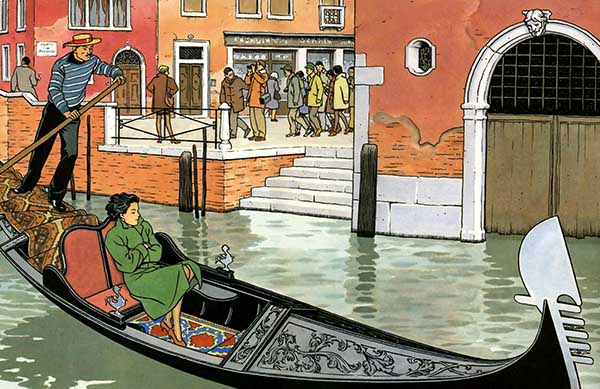

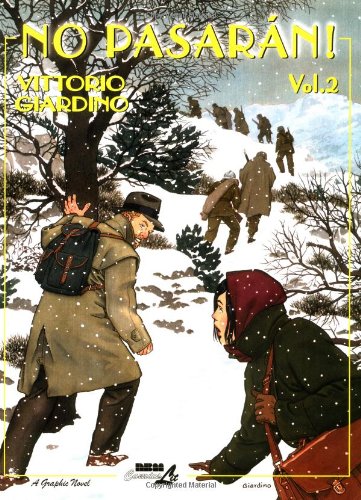

The first album about Max Fridman, Hungarian Rhapsody (90 pages), is a leap of seven miles in Giardino’s career. Some consider Hungarian Rhapsody one of the best European comics of the 1980s, which immediately became an instant classic. With this graphic novel, he enters a phase of more complex storytelling, without length restrictions, which was characteristic of Sam Pezzo’s adventures. Hungarian Rhapsody was published in 1982 and won the Yellow Kid award (Lucca) that year. The Max Fridman series is set in Europe of the late 1930s, moving towards World War II. Chiaroscuro was abandoned in favor of color, and it was a clear and definitive transition to the “clear line.” Since then, Giardino has been coloring his comics using watercolor. The second part of the series, The Gate of the Orient (62 pages), was released in 1986. No Pasaran is this series’s final and most extensive work (spanning 162 pages). It is dedicated to the Spanish Civil War and was published gradually over about ten years, in three books: in 1999 (54 pages), 2002 (46 pages), and 2008 (62 pages).

The Max Fridman albums have been sold in about twenty countries, which puts Giardino in a privileged position to work on albums the way novelists do, presenting a finished work to the publisher without meeting the demands of deadlines. Of course, this wouldn’t be possible based solely on sales in Italy. Moreover, at specific points in his career, he was more famous elsewhere than in Italy: in France, America, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain…

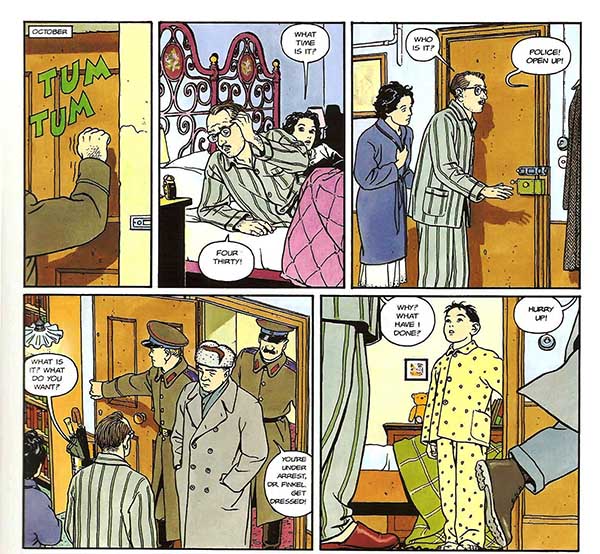

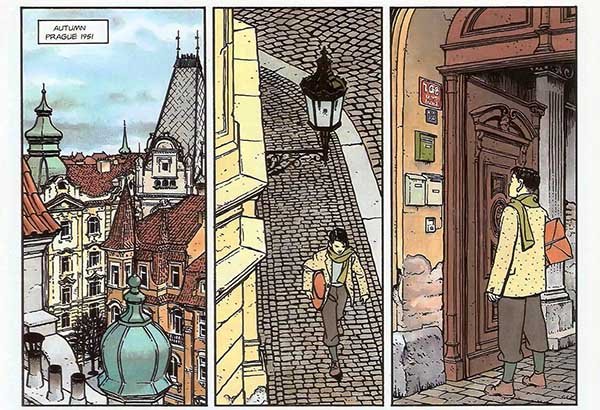

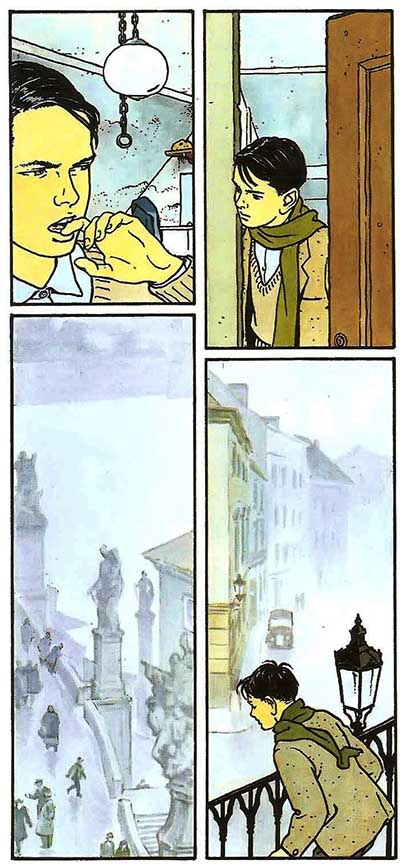

The third series, Jonas Fink (translated in America as The Jew in Communist Prague), also focuses on historical narration. The theme revolves around the upbringing of a Jewish boy/young man in the Stalinist environment of Prague in the 1950s. Giardino began the series in the 1990s. Three albums have been released. For this series, he won the Alfred Award for Best Foreign Comic at Angoulême in 1995 and the Harvey Award in San Diego in 1999.

Little Ego is a series on the other, “lighter,” history-unburdened side of his opus, although fans of sexy comics particularly revere this series by Giardino. In the 1990s, Glamour International launched Little Ego as a sexy comic for elite comic consumers. However, the sales of this comic exceeded all expectations. Alongside Little Ego, there is Eva Miranda, a soap opera written by Giovanni Barbieri. Unfortunately, it performed poorly in the market and never grew into a series.

Giardino entered the world of comics quite late, at the age of thirty-two, abandoning a lucrative career as an electrical engineer in 1978, after ten years in the profession. Indeed, there is something in the precision of his stories that resembles an engineer. Giardino once said, “designing an electric motor and creating a story are very similar.” However, he realized that being an engineer during the day and an author at night wasn’t possible. He decided to step into the uncertainty of creative work in comics and remained there forever, without regretting a moment.

Almost manic precision and attention to detail, both in drawing and in writing, have made Giardino famous and respected even outside comic circles (he, for example, needs to know if the cable car operated in Barcelona during the Civil War, and he admits that a professor from Istanbul noticed a mistake in the second album about Max Fridman, The Gate of the Orient, set in 1938: at that time, fezzes were banned by Atatürk’s decree), but also known for his proverbial slowness: fans (and publishers) have to wait for years for the sequels to his series. According to him, this filigree approach to creating comics and staying within the stylized framework of realism has another possible root: “it’s possible that it stems from my inability to omit or simplify.”

Giardino is attracted to partially forgotten tragedies and historical enigmas and desires to dive into them when archival sources are available for research. To some extent, it is a recreation of the historical context for the purposes of the story he wants to tell with pen, ink, brush, and watercolor, a kind of comics meditation on history. The author highlights a fundamental influence in this domain, Corto Maltese by Hugo Pratt, particularly his masterpiece Corto Maltese in Siberia, as Giardino calls it. It’s about the inseparable intertwining of significant historical events with the individual stories of imaginary characters. Hence, there is a need to “reconstruct” the life of a fictitious character during the preparatory work to create a comic with the same care with which the author familiarizes himself with the historical context into which he places them.

Some things in Giardino’s stories don’t happen explicitly but through subtle threat or suggestion. There is a certain distance and restraint in Giardino, from diving into the frenzy of action, although he demonstrated that skill excellently in Sam Pezzo. He inclines to explore more psychologically nuanced aspects in later series with his calmer and much more thoughtful comic language, dealing with suggestions and hints instead of overt action.

In the portrayal of Giardino’s characters, the contrast between good and bad fades. For the large exhibition ‘The Fifth Truth’, held in Bologna in his honor, he once said that if the title depended on him, he would call it ‘A Pile of Lies.’ Giardino’s stories do not suggest that we possess the truth, nor do his characters. They intertwine multiple truths. That’s why conflicting interpretations of history stimulate him in his work. In the preparatory research for No Pasaran, he read books like History of the Spanish Civil War by Hugh Thomas (detailed, objective, very pragmatic, and full of facts) and, on the other hand, Marxist interpretations or authors such as George Orwell and Arthur Koestler.

George Orwell, John Dos Passos, Arthur Koestler, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Andre Malraux, Graham Greene, John le Carré, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling… many literary names… are many literary influences in Giardino’s comics, sometimes more directly in style, sometimes in atmosphere, sometimes just in themes… At the same time, one sometimes forgets the cinematic influences on his comics, Orson Welles (The Lady from Shanghai), Michael Curtiz (Casablanca), Alfred Hitchcock… However, Giardino himself recalls the influence of Italian neorealism on his comics, albeit late, not the proletarian one but the bourgeois, as we find in Visconti’s film Senso.

Giardino has been busy collaborating on a monograph about his hero Max Fridman. Such a monographic book, subtitled ‘fragments of biography’, he says, allows him to do something that the format of a comic album doesn’t provide, to “tell” many threads from the life of his character through a non-comic medium for which he would otherwise need many albums that he doubts he would have time to do, given his proverbial thoroughness and slowness.

ZORAN DJUKANOVIC: Some comic authors are obsessed with depicting clothing, some are obsessed with depicting cars and vehicles, some with interiors, rooms, and some with architecture… However, with you, there is an obsession with the entire context of your stories. Where does this “completeness” come from?

VITTORIO GIARDINO: In my historical comics, I want to be as precise as possible to respect reality and to give an accurate idea of the era in which the story takes place.

DJUKANOVIC: When and how did your deep interest in the historical context of your narratives develop? Was there a moment of initiation?

GIARDINO: Since my youth, history has always fascinated me, even before I became a comic book artist.

DJUKANOVIC: History and context indeed, but not a confessional, autobiographical approach. You once said you always tried to avoid autobiography. Why?

GIARDINO: Fortunately, my life has been very peaceful and wouldn’t be interesting to others.

DJUKANOVIC: However, it didn’t stop you from saying that Flaubert also emphasized that the authors inject much of themselves deep beneath the surface into their work.

GIARDINO: Of course, I always infuse myself when creating characters. Every story I tell is also a confession, but always unrecognizable and altered. Sometimes, my friends recognize some situations I have experienced, or they can identify people I’ve met in real life in some characters. Still, only those very close friends can recognize them, no one else. Anyway, it doesn’t matter.

DJUKANOVIC: In one interview, you said, “Women are dangerous.” Why?

GIARDINO: Women are dangerous because they are essential in a man’s life, at least for me. Many choices in my life have depended on women, so a woman, if she wants, can ruin a man. Of course, it’s also true that the opposite can happen.

DJUKANOVIC: You say, “We don’t possess the truth, nor do my characters.” Is that your poetic approach in your works?

GIARDINO: I wouldn’t know. I note some factual situations, but I’m not sure about that.

DJUKANOVIC: In Sam Pezzo, you used a different comic language, with many chiaroscuro effects, black and white contrasts that José Muñoz extensively used in the series Alack Sinner. What were the reasons for later abandoning it?

GIARDINO: In Sam Pezzo, I used a black-and-white technique (and quite dark) because I wanted to create a noir comic. So, color seemed inappropriate to me, but it can’t be said that I abandoned color because it was the first comic I drew as a professional. I started with black and white, then switched to color.

DJUKANOVIC: You refuse to acknowledge that your “clean line” style was influenced by anyone from the Belgian school (Hergé, E. P. Jacobs, Jacques Martin…), pointing out that European painting and the comic medium were strongly influenced by Japanese illustration and painting?

GIARDINO: There were influences from Hergé and others, but perhaps Gauguin, Van Gogh (few people know their drawings), and Hokusai had a more substantial impact.

DJUKANOVIC: Also, you once said, “I didn’t choose my style, it came on its own?” How?

GIARDINO: I am entirely self-taught; I didn’t attend any art academy, and perhaps that’s why I simply draw what I see and how I see it. Many aspects of my “style” also depend on the tools I use. If I used charcoal, the result would be different. So far, I have almost always used ink, pen, and brush. Who knows what the future holds… Of course, I have always drawn with passion. From the age of four until now, I have drawn with the same passion.

DJUKANOVIC: Do you always color your comics? Do you regularly use watercolor? Do you ever use a brush, or is your realm of drawing expression exclusively tied to the pen?

GIARDINO: Yes, I color my pages. So far (almost always) with watercolor, I like it because of its speed and looseness. On the other hand, I don’t know and don’t want to learn to use a computer for coloring. Of course, somebody can achieve impressive effects this way, but I like the “craft.”

DJUKANOVIC: Which of the awards for your contribution to comics was most dear to you – Yellow Kid, Alfred, Harvey Award, St. Michel…?

GIARDINO: All awards are important, just don’t let them make you think you’re good because of them. You risk becoming conceited this way, but the learning process never ends in my profession.

DJUKANOVIC: Realistic, detailed, precise… which term would you prefer to describe your work?

GIARDINO: This is a question for a critic. I hope I have done my job honestly. Yes, I would like my work to be honest.

DJUKANOVIC: Your comic-making process is lengthy and exploratory. What is your greatest pleasure, and what is the most significant burden when working on a comic?

GIARDINO: I love all stages of creation: research, documentation, scenography, sketches, drawings, and coloring. I like everything. What I like least is discussing publication with publishers when the story is finished.

DJUKANOVIC: Why is attention to detail so significant in your comics? When you put yourself in the role of a reader of your comic, what is most vital for you to achieve in their consciousness?

GIARDINO: I observe details in real life; even if I don’t want to, they “speak” to me. For example, when you enter a house and look around, you can infer a lot about the people who live there, even if you haven’t met them yet. That’s why I put a lot of detail on the pages, maybe even too much. Even if they don’t consciously notice these details, readers still experience them without realizing it.

DJUKANOVIC: You mentioned once that you create comics so ambitiously that they can be read even in three hundred years. Would you agree with the opinion that your best work is Hungarian Rhapsody, which some critics consider the best European comic of the 1980s?

GIARDINO: Which one is my best work? All works are my children, and I don’t want to make distinctions. As for my ambition, yes, I am ambitious. Let me explain a little better. Comics, like novels, movies, music, etc., can be created for fame and wealth. I call this “working for fame.” I’m not very interested in that. One can also create comics to tell stories that would be interesting to future generations, comics that become “classics.” I call this: “working for immortality.” I don’t know if I will succeed, but that is my ambition.

DJUKANOVIC: You pay great attention to cities, which are the settings of your comics. Which city do you enjoy depicting the most?

GIARDINO: There isn’t just one city. The stories feature cities that have stirred my emotions even before I started drawing the comic. If I had to list them, I could mention Paris, Barcelona, Venice, Istanbul, Prague, Budapest, Lisbon, Trieste, Krakow, Tel Aviv, Thessaloniki… but I’m afraid the list will be long.

DJUKANOVIC: You say that rational construction comes later, and emotion is always first? A short time for emotion and a very long one for analyzing that emotion? Describe that first emotional spark in you?

GIARDINO: I don’t think I’m capable of that. Emotions can come from travel, life experience, books, movies, music, or anything. It’s true that the feeling can engulf you suddenly and unexpectedly, and can be intense but very short-lived, while the process of creating a story itself takes much longer.

DJUKANOVIC: Some of your comics were first serialized in comic magazines, and then in albums. At the same time, you had the privilege of creating your stories in the manner of a novelist, working on a graphic novel and offering it to the publisher only after completing it. How do you view seriality? Is seriality an inseparable characteristic of the comic medium?

GIARDINO: Throughout history, the most successful comics were those serialized, and the main character was more famous than the work itself. This can also happen in literature (for example, Commissioner Maigret), but it happens more often in comics. The serialization of comics is neither inherently positive nor negative; there are serialized comics that are true masterpieces and graphic novels that are terrible.

DJUKANOVIC: Do you find time to read comics yourself, classic or contemporary? What does the hedonism of reading comics represent for you?

GIARDINO: I read comics, but I don’t have much time or the opportunity to read everything that has been published. There are so many of them! I often reread a classic; it can always teach us something.

DJUKANOVIC: What other forms of culture do you most enjoy consuming? Film, literature, theater, music…?

GIARDINO: I can’t answer because I enjoy all forms of expression. Maybe I prefer literature and film more than others, but as a student, I also tried theater, so…

DJUKANOVIC: You said something that seems very important and interesting to me – I’m not an illustrator but a comic book author who does illustrations, and you also said the same applies to André Juillard. Can you explain a little more?

GIARDINO: When I draw something, I always try to tell a story. Even in my illustrations, you can sense a story. The narrative dimension dominates the imagination. That’s why I don’t feel like an illustrator. I like to invent stories, so I have little time for illustrations.

DJUKANOVIC: Your Little Ego series also has a loyal audience, even a kind of “cult.” You once mentioned you did it in between historical series to relax from heavy topics in your work?

GIARDINO: Exactly. It was very light and exciting. Drawing female figures gives me particular pleasure. I’ve wanted to continue the story of Ego for a long time; I know it’s waiting for me. I already have quite a few stories written. I hope to find time for it someday.

DJUKANOVIC: What is the share of illustration work in your career? You worked on illustrations for Vogue for two to three years; on the other hand, you worked on illustrations for children…

GIARDINO: I worked for Vogue and other fashion magazines, but (almost) never did illustrations for children, except many years ago for the magazine Je Bouquine. I do a lot of illustrations, for ads, catalogs, or just for myself (I’ve published six books of “personal” illustrations), but my most demanding work remains comics. After all, each page of my comic has 7-8 panels, so in a story of 100 pages, there are 7-800 different drawings.

DJUKANOVIC: What is your experience with publishers? You once said that Sergio Bonelli had an incredibly fair attitude toward authors?

GIARDINO: I don’t have a general opinion; each publisher should be viewed individually. There are excellent publishers and less good ones, as in all professions. Often, authors and publishers feel like two opposing sides, against each other. They should be allies; both sides want the books to be read. If sales go well for the author, it goes well for the publisher, and vice versa. Both are needed to allow reading to those who want to.

Interview by Zoran Djukanovic