Souvenir is described in the back-page blurb as Sara Jewell’s first graphic novel, but also as a “collection” – “In this deeply intimate collection, Sara Jewell searches for meaning in a chaotic past…” The ambiguity between collection and novel is significant, because Souvenir doesn’t quite fit into either category.

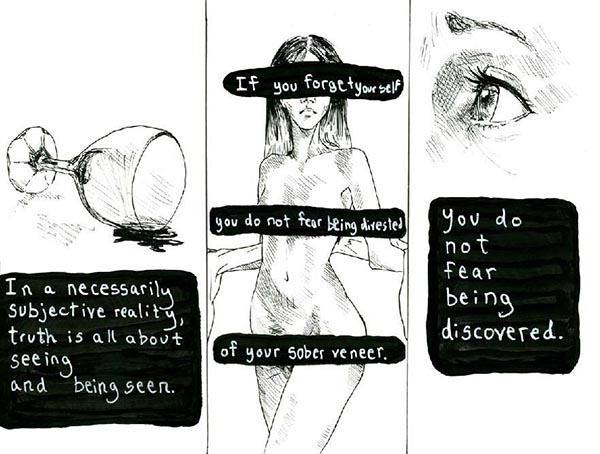

It’s just over eighty pages long, broken into five short sections and an epilogue. It has a very hand-made feel: hand-lettered, many of the pages with grey or textured brown backgrounds, evidently scanned straight from drawings on cartridge paper or card. Some pages use fairly conventional comic book layout, with panels and speech bubbles, but a lot more show single unframed drawings accompanied by little bits of text, or break up the page-space in various experimental ways. Some sections are in portrait format, some in landscape.

Jewell tells us in her Author’s Note that “I wrote the majority of this book in my twenties… I’m thirty-three now, an age I once thought I’d never reach”. The impression given by the different sections, however, is that they may have been written at quite different times, because each section seems to have its own particular style – scratchy black and white pen-and-ink, or black and white with grey washes and white highlights, or black and white with pink washes, or colour drawings using crayons and chalks.

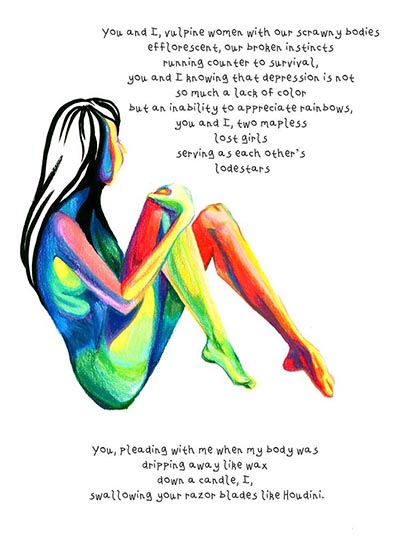

Some of the drawings are good, some clumsy. The writing, on the other hand, is generally excellent and sometimes really poetic: “Nights alone, you take midnight runs in the humid suburban dark spangled with street lights, as hard as you can, for as long as you can… You watch the trembling stars long after the world’s fallen asleep, the mattress pitching under you like a boat in a tempest…”

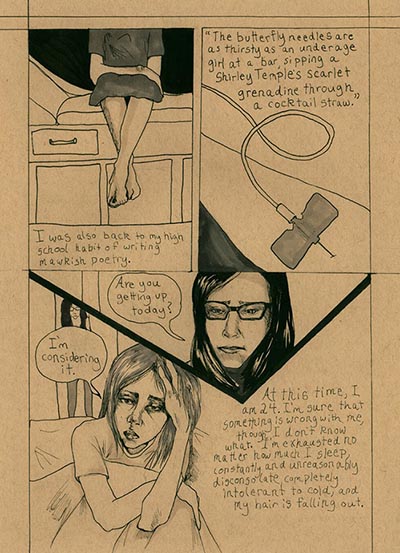

Why did Jewell once think that she would never reach the age of thirty-three? Partly because as a young woman she spent a lot of her time exhausted, depressed, self-harming and contemplating suicide, until eventually it turned out she was suffering from a serious undiagnosed chronic illness (Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune disorder affecting the thyroid).

“This book carries a content warning for allusions to self harm and sexual violence”, the Author’s Note tells us. But there’s nothing too graphic. A friend of Sara’s tells her about the butterfly project, which says that when you feel like you need to hurt yourself, you should draw a butterfly on your skin instead, and name it after someone you love. You’re not allowed to wash it off – you have to let it fade; and if you hurt yourself before it’s gone, you’ve killed the butterfly. An illustration shows a butterfly perching on a bleeding wrist.

This little section forms part of a whole chain of imagery about butterflies. Jewell’s uncle collected them and preserved them on pins behind glass; as a child she caught them herself, but always let them go; we glimpse her trying to keep one alive in a jar, but it dies; and when she is diagnosed with Hashimoto’s disease, she mentions that the thyroid gland is butterfly-shaped. Butterflies, of course, are proverbially both beautiful and fragile, also proverbially short-lived. Jewell’s ideas about butterflies are clearly related to her self-image and her feelings about her own existence.

Along with the allusions to self-harm mentioned above, there are also references to sexual abuse (“Was that really rape, though?… Did I say yes? Did I contradict myself?”) and alcoholism (“You carry everywhere a little plastic water bottle refilled with vodka… You take shots like a marksman.”) These are set within the wider context of Jewell’s depression, a condition which “cannot be cured – it can only be treated”.

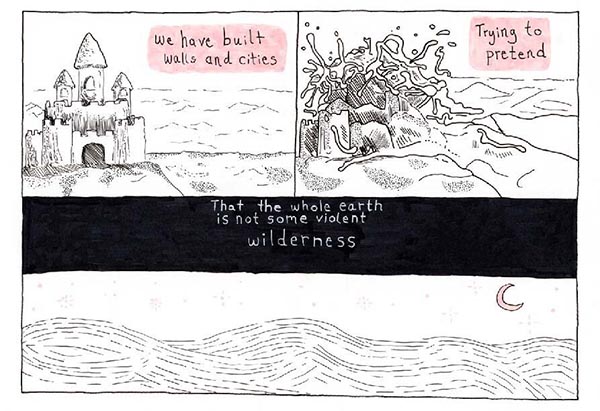

Reading the book, you find yourself hoping that the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s will help to unlock and explain Jewell’s exhaustion and depression, and thereby bring some optimism and stability to her life. The last section – an epilogue titled ‘Holding Pattern’ – shows her in an airport with a partner, waiting for a plane which never arrives: “We’ve waited so long in this terminal that we’re the only ones left… We’ve waited so long that our lives are half over… I think our flight’s been cancelled… All we can do is keep waiting.” There are unmistakeable echoes of Waiting for Godot, and Beckett’s almost gleefully grim view of existence. The final picture shows two skeletons recumbent on an airport bench. In this section there does seem to be a new toughness of attitude, an awareness of ageing along with an acceptance of the unrelenting nature of existence.

Ultimately, Souvenir is perhaps too fragmented to qualify as a novel – there is very little sense of narrative, and although there are other characters apart from Jewell herself, they’re nebulous and marginal. The different sections do link together, but only loosely. Basically it’s a book about states of mind. Its coherence is poetic rather than structural. It’s a fascinating but flawed experiment.

Sara L Jewell (W/A) • Fieldmouse Press, $14.95

Review By Edward Picot