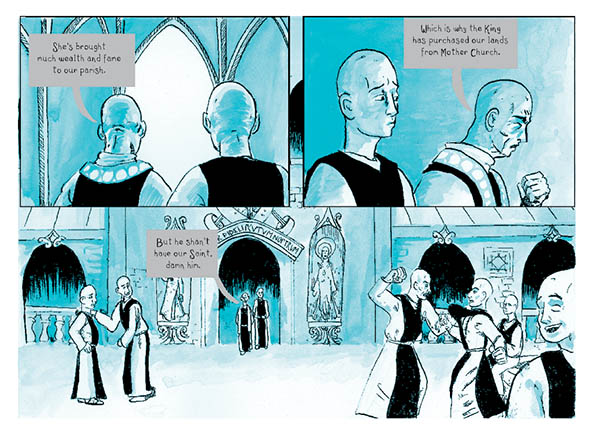

The Ardent by Carl Antonowicz, from Fieldmouse Press, is set in an imaginary medieval land. It opens in a monastery which is closing down because its lands and buildings are being taken over by the crown. Most of the monks have already forsworn their vows, but the last and most dedicated is a monk called Odulf, who has taken a vow of silence.

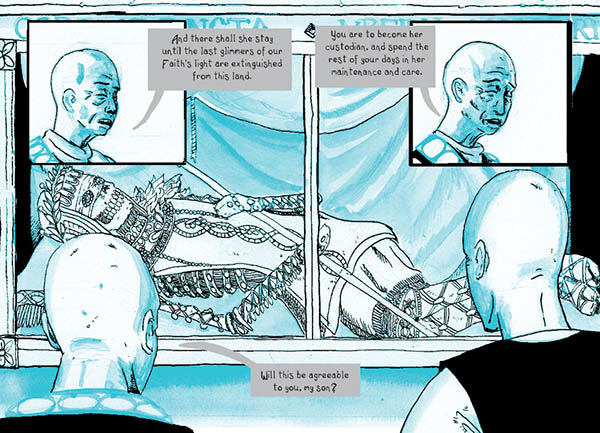

The monastery’s most precious relic is the jewel-encrusted skeleton of its founder, St Ursina, who was martyred for her faith. Odulf is given the task of taking this skeleton for safekeeping to a sister-church in a place called Kirkgart. “En route”, the blurb tells us, “his faith will be tested to breaking point”.

The book is 170 pages long, A4 landscape format, and mostly drawn in black outlines with blue washes, although there are ‘flashback’ sections which use pink or grey washes instead. One of the first things you notice is the rough and ready quality of the draughtsmanship. There are buildings drawn out of perspective, and examples of clumsy figure-drawing, in abundance. Don’t be put off, though. Antonowicz’s drawing is good enough to carry the story – it even contributes to the grungy feel of the book – and the story itself is unfolded with a considerable degree of skill.

On his journey to Kirkgart, Odulf meets three other people – first a gamekeeper called Elgar, who arrests him while he’s sleeping in the woods; then a homeless boy called Goswin, who accosts him to beg for food; and finally a nameless old witch-lady, who lives in a hut by herself in the wilderness. Each of the three tells him a ‘flashback’ story. The way that these stories are drawn out of them by Odulf’s silence is skilfully managed.

Elgar tells how he ended up living alone because he caught the girl he was intending to marry making love to the Marquess, part of the noble family that employs him. Goswin, the homeless boy, tells how his mother and father both ran off and left him after their harvest was ruined – and this is probably the best-drawn part of the book, because it’s made up of simple ‘stick-man’ drawings which represent Goswin’s childish outlook.

The witch-woman retells the story of St Ursina’s martyrdom from the pagan point of view – Ursina wasn’t martyred at all, she claims, but committed suicide because she was first raped by the soldiers of the Christian army and then rejected by her own family. Thematically this is one of the most interesting parts of the novel, because it challenges Odulf’s ideas about Ursina and her sainthood, and you sense his faith beginning to waver; but it’s also the part where the clumsiness of the drawing becomes most intrusive.

The dominant note of the whole novel is cynicism. Antonowicz presents us with a world full of violence, injustice, greed, lust and pestilence. Christianity is either an excuse for violence and persecution, or simply an irrelevant superstition. Despite this over-arching cynicism, however, the characters in the story are actually fairly moderate and tolerant in their behaviour towards one another. Elgar the gamekeeper becomes friendly towards Odulf once he realizes that he isn’t a poacher. Elgar’s employer, the Duke, simply dismisses the monk instead of punishing him for trespassing. Goswin’s parents, who ran away from home partly to escape from him, take him back when he finds them in a new town running a tavern, on condition that he stops talking so much. The witch-woman helps Odulf on his way by giving him a bowl of soup.

The main weakness of The Ardent, without giving away its ending, is that it’s too one-note. The grungy cynicism with which it opens is pretty much exactly what we’re left with at the end. Despite the roughness of the draughtsmanship, it’s a genuinely engaging read and the characters are well-developed. But it takes us on a journey which doesn’t really deepen our understanding.

Carl Antonowicz (W/A) Fieldmouse Press, $20.00

Review by Edward Picot