Ned Wenlock is a quietly rising star in the international comics scene. Born in the UK, Wenlock has lived in New Zealand since the age of 13, where he works as an animator and illustrator. In recent years his comics have shown up in the respected anthologies Faction, Bristle, and From Earth’s End: The Best New Zealand Comics.

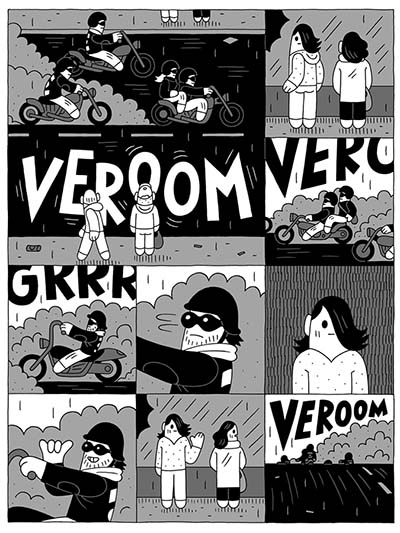

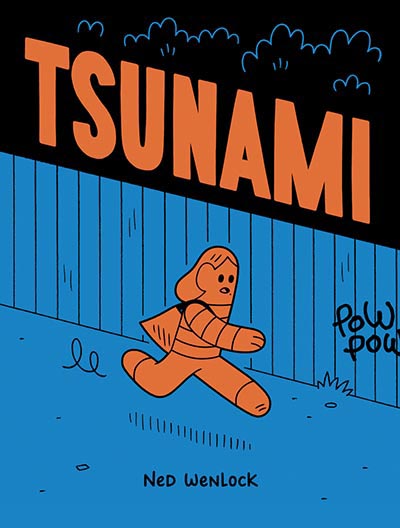

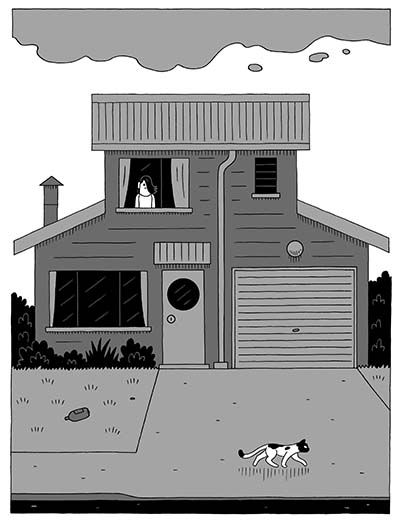

Wenlock’s debut graphic novel Tsunami is set to be released on May 6 by Montreal-based publisher Pow Pow Press. Drawn in a disarmingly cartoony style, Tsunami is a coming-of-age story that is both devastating and hilarious, and an unflinching look at the consequences of bullying. Sammy Harkham, creator of Blood of the Virgin, calls Tsunami a “regional, personal, novelistic story in a sophisticated and distinct style that harnesses the elements of the form into a wholly unique language” while Dylan Horrocks (Hicksville) calls the book “deliciously unsettling.”

In this conversation with fellow Pow Pow author François Vigneault, Ned Wenlock discusses the sometimes terrifying prevalence of violence in young people’s lives, the importance of giving equal weight to different sides of the same story, and the challenges of creating a film noir-inflected story for adults when your protagonist is a self-righteous 12-year-old “twerp.”

François Vigneault: Tsunami is a fictional book about the coming of age of a young person. Is it based at all on your own experiences, or was it inspired by something else?

Wenlock: It is a little bit based on personal experiences. The overall story is totally made up, and the characters are all totally made up. None of that is real in terms of the actual narrative or anything like that. But when I devised this idea of doing the story in short scenes, to get inspiration for a lot of the scenes, I just went straight into my childhood, or things that I saw around me at the time that I was doing it.

And so a lot of that is actually quite real, but transposed to this fictional story. I think that was useful, because I’m more interested in the emotions and the energy of a story, rather than the plot necessarily, so in order to get into those things I had to feel like I had lived it myself anyway, so there are a few examples in there. Like I have this idea, of a moment that I wanted to happen. And then I had to go sifting through my childhood and go, “Did I have something that was relevant to that? And what did that feel like?” And then I was able to draw through it.

FV: I know you were born in the UK and you moved to New Zealand at 13, and of course that made me think about Charlie’s story, because she’s a young person who moves to New Zealand. Was that part of the inspiration there? And were there any kind of “culture shock” moments for you?

Wenlock: Yeah, absolutely. I think the thing is, all the characters are basically me, in one way or another. Even Gus is a little bit of me. Because when I’m writing these characters, I think of them as being the main character. And so then I think about “What does this feel like, to be this sort of person, in charge of this sort of thing?” And so you take different parts of your life to do that.

With Charlie, yeah, she was very much like me when I first got to New Zealand. The feeling of New Zealand, compared to the UK, was quite stark. In the UK you have to hold a little bit of history. It’s like everywhere you walk, there’s something or other, you are walking where the Romans walked, or whatever. Come here to New Zealand, and everything felt like a diorama, like it was cardboard. There’s so little history, visible history, I mean. I know there is history here, but it’s like there’s no old stones laid down or anything like that. It felt very temporary. So that’s the kind of feeling I wanted to give her. Like she had this history back in England, with her friends as well. And on getting to New Zealand, it’s so basic, and raw, and there’s nothing to it. That’s just the initial reaction you have, and then obviously when you live here and you make friends and all that kind of stuff, it changes. But that was definitely an initial thing that I leaned into.

FV: It must have stuck, since you’ve been in New Zealand for a while now, right?

Wenlock: Yeah. That’s the thing, we lived in Wellington for 10 years, and then we moved up the coast here to Paekākāriki, which is like a big sprawling kind of suburb. And I had the same feeling again, it is like you move out of a city into the suburbs and it’s “Oh, there’s just a lack of culture here, there’s a lack of things going on.” Yeah. I do often have that feeling.

FV: You get into that in the book a little, right? There’s the sense that the kids are looking for something to do. They’re sitting around in trees, drinking a beer, trying to figure out what they can do. And that often is getting into trouble.

Wenlock: Absolutely, absolutely.

FV: I really liked that you mentioned the idea that all the characters are yourself, and you see yourself in all of them, because I definitely felt that reading the book. Peter, who’s 12 in the book, is the protagonist in many ways. But even your antagonist, Gus, who’s a violent neighbor, who is very troubled, you get into the details of his life and his family background. And then there’s Charlie. They all have their own volition, their own energy that’s moving them through the story. And you get a sense that the story is happening because multiple people have opposing things that they want, or ways they want to interact with each other. And then you’re pinging off of that.

Wenlock: Yeah.

FV: I find it very interesting that you mentioned that you’re not very plot-oriented, because the plot of Tsunami is actually quite tight. Every little thing leads to something else. Every scene that you have sets up the ramifications of what’s gonna happen next.

Wenlock: Oh, that’s true. When I say I’m not very plot-orientated, what I mean by that is that I think I’ve got this puzzle brain, it likes to do puzzles, to figure things out. Left to its own devices, my brain does these plot things anyway. Especially something this long, I had never written anything quite this long before, but I found that I was battling the plot all the time. My head would go to something, and I’d be like, “Oh, that’s exciting.” And then I’d be going, “Whoa, let’s just let the characters do it. Let’s see what they do.” So yeah, there were a lot of times where the plot just became too tight, and I just had to let it go. My head was already thinking way into the future, like, “Where’s this gonna pan out, and what’s gonna happen here?” and stuff like that. And I think the problem with that kind of thing, is that you get into those kinds of cliche shock/horror things that don’t feel organic. That’s the reason why I battle it a lot. Yes, maybe I am plot-orientated, but I try and steer my way away from it, right? You know what I mean?

FV: That definitely makes sense. Since you brought up the idea of shock or horror, one thing that I found interesting is this book won the New Zealand Society of Authors Award for best first book, but in the youth and children category. First off, congratulations, that’s fantastic.

Wenlock: Thanks.

FV: And then second, Tsunami does get quite tense, there’s some sad and even shocking things happening in the story. How did you balance telling a story about adolescence, but from an adult point of view?

Wenlock: I think when I was writing the story, I wasn’t writing it for kids. I wasn’t thinking about a young adult audience at all. I was just thinking as an adult. All the comics I’ve done in the past have been quite humorous, because the style that I draw in lends itself to humour. I never thought that my style would work doing something serious. But for this one, I just thought “Why don’t I just try and shake off the humour, turn everything off.” And go at it without any irony, just go through it and see if I can tell a convincing story. And… I’ve just lost the thread of your question! What was your question again?

FV: [Laughter] I think you answered it very well, in that in some ways you didn’t have an audience in mind for it. You just were creating it for yourself and you wanted to explore.

Wenlock: Yeah! So the whole point of it for me was that, I like the idea of taking this person, who saw himself as a little angel kind of character, and then turning him into the opposite of that. Just a really simple story strand, going from good to bad. I just loved that character. Peter was based on myself from that age, thinking about what a little twerp I was, how righteous I was, and how I thought everything I did was perfect, that kind of thing. I wasn’t quite like him, but very similar. I just thought, “I want to follow this character.” And I thought it would be humorous. Even though I wasn’t trying to be humorous, I thought it would be humorous anyway, in a dark kind of way. I was really just satisfying myself more than anything. So that’s why it has an adult view on the whole thing.

I’ve had a lot of responses from kids here in New Zealand. A lot of them, there are strange kids who love it, who really get into it, and don’t mind the gritty stuff and all that. But then there’s a whole bunch of kids, who are really in it just for the plot, and they just read it as a plot thing and they’re like “Oh, it doesn’t have a very satisfying ending.” You know what I mean? It doesn’t. It doesn’t do what all our other YA novels do, which is to end on a high. So yeah, it’s hard, having won that award, addressing that question. I’ve had a lot of interviews where that question has come up, “Do you think the ending’s too rough for young adults?” It’s like, I didn’t write it for them.

FV: I absolutely understand. And Pow Pow has decided to market it, based on your recommendation, as an adult book. And I think that’s right. Although, to tell the truth, it reminded me of books that I read when I was younger, and I turned out pretty okay! It’s more extreme, but if you think about, say, Lord of the Flies by William Golding, I read that when I was pretty young, and that also doesn’t have an upbeat ending!

Wenlock: That’s right. There were a whole bunch of stories that I read when I was at school that I remember quite vividly, more so than any of the other stories we had to read. And they were all on this kind of similar sort of theme, and they were things like and if you ever seen Unman, Wittering and Zigo? It’s about a school, and some kids that end up murdering someone. And another story called ‘The Swan’ by Roald Dahl. And Lord of the Flies, like you said. Those are the ones that really just stuck with me. I’m interested in that kind of stuff. As an adult, too, I love those types of things where a normal character gets in way over their heads, and is in a terrible situation. It’s like a film noir type thing. They’re doomed from the start, but it’s all of their own making.

FV: Which, when the protagonist is 12 years old, that is grim! But it’s also true in some ways.

Wenlock: That is grim. That is grim. But actually going to that point, the reason that I made it about a 12-year-old kid, and in some ways the reason I wrote the story, is that I had done a lot of music videos, and I’ve made short films, and I’ve done a lot of short comics and stuff like that. And the overriding criticism from people has been, “You don’t ever have conflict in your stories.” I thought long and hard about this, and I thought, “Yeah, you’re right. I actually don’t go in for conflict.”

So another part of coming up with this story was that I wanted to really get into conflict, and even violent conflict, rather than just a problem at work or whatever. And I thought in New Zealand, like there’s not many places you can get into that kind of conflict. Obviously there are gangs and things like that, but I know nothing about that. So I was thinking, “Where have I had conflict in my own life?”

And it goes back to school, and particularly the end of primary school, the start of high school, because that’s when you get into fights. When you get older, you talk about it, you talk your way out of it. You don’t end up fighting, you don’t get into physical conflict. That’s another reason why I wrote about that particular age group.

FV: I do think that you really capture that, the sense of how weirdly dangerous it feels at that age, when you are 12 years old, and the different kids are growing up at different paces. Some kids are bigger than other kids. Some kids, they just wanna play, and have toys, and things like that. And other kids are already moving into their sexuality and everything, and everyone’s all lumped together.

Wenlock: Yeah.

FV: It’s not very even. And so it is almost a breeding ground for tension, and sometimes that can be very physical. I remember that sense of physical violence and fighting, which is totally weirdly available when you’re young. When the adults weren’t around it did feel very dangerous and strange.

Wenlock: Absolutely. Absolutely. Earlier you were asking, “Does any of this come from my real life?” When I wrote it, I wasn’t thinking about where it might be coming from. But afterwards, after I’d written it, I sat with it for a while, and someone asked me about it. And I was thinking, “Yeah, where does it come from? Why have I thought about all these violent situations?” And that overriding feeling of doom in some ways.

And I was thinking like when I was 14, I went to boarding school. My family moved to New Zealand when I was 13, and then we moved out of the city, into the countryside, and I had to go to boarding school. And so I was surrounded by all these boys 24/7, and I was living in this really hostile environment, and I think a lot of that came out in this, that feeling. Like the bit at the start of the book, where Gus gets Peter into a headlock on his bed. That’s basically happened to me. And so I was able to really get into what that feels like, in what should be a safe environment, in someone’s bedroom, but having this situation that you have no control over, it’s kind of horrifying in a way.

FV: I love that scene too, because you get into the strange complicity that children have in their own bullying in some ways, right? Peter goes along with it, he’s like “Oh yeah, everything’s fine, Grandma.” And it’s very strange.

Wenlock: Yeah, because it’s embarrassing! His Nana thinks that this is his friend! It is just embarrassing, because if you don’t have any friends, to admit that you don’t, for a start, but also to admit to family members that this shit’s happening in your life! It’s awful.

FV: I think that a lot of readers, young and old, are gonna see something in it of their own life today. Because these things are eternal. We’d like to think that things are always getting better, but there’s a lot of ups and downs, and it’s not necessarily that kids are all totally in touch with their emotions or anything these days. So I think that the portrait that you give of bullying, and the ways that conflict can arise with adolescent kids, I think it’s very powerful, and I think a lot of readers, adult readers, and maybe even some mature younger readers, are gonna really connect with it. You’re handling a sensitive but important topic.

Wenlock: Oh, thank you. That was always the intention, not be didactic about any of it, and there’s no savior character, or anything like that. It is all just people trying to get through life, in their own ways, dealing with their own pasts and their own kind of set up. And I just find that stuff really interesting, and it could be about anyone, but it just happens to be about primary school kids.

FV: I think it’s very appropriate that the book’s not just in black and white, but in black and white and shades of gray, right?

Wenlock: [Laughter] Yeah. It goes along with the sort of film noir theme as well. Like I think if it had been in color, with these cute looking characters, it would’ve been too much to take. Black and white sort of pulls it back a little bit and allows it to be more real in some ways. With bright colours I think it would’ve been a little too cartoony.

FV: Speaking about your style, I think that’s something that almost any reader who sees Tsunami for the first time is gonna really notice right away and hopefully connect with, is the fact that you have a very unique cartooning style. How did you develop that? Were there any specific influences on you, or did that come out of your animation background?

Wenlock: No, it didn’t come out of animation at all. Previously, before this style, I was working with a brush and ink, and illustrating characters more realistically, still in a simplistic style, but slightly more realistically. And I was finding that my perfectionist tendencies were stopping me doing work in a way. I would do a drawing, and I wouldn’t be happy with it, and I’d have to do it again, and so on. I felt like I was chasing someone else’s style. I don’t even know whose style I was chasing, but like in terms of that brush style, the American sort of brushing sort of thing. I did this one project, I spent a year on it, and I couldn’t get into any kind of flow, and it was doing my head in. I thought, I’ve got to come up with a simpler style. In some ways I don’t care about the style. It’s more about the story and the characters and what’s going on inside it.

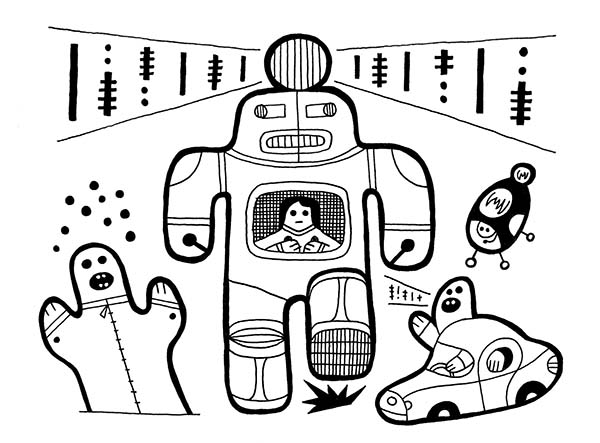

This was quite a few years ago, back in the 2000s kind of thing. And so I was looking around at things at the time and I was really into tin like tin robots and things, and also I’ve been looking at images of Mexican clay pottery. And the idea behind this was, if you mold a character, like just the outline shape of that character, and then you just draw the lines inside the character to represent like a shirt or whatever, that will be a super simple and fluid kind of style to work in. And my initial drawings were just that. They were really, really simple. I’d even draw cars like that, with the wheels inside the shape!

Over time they have become more and more like actual, tubular-type people and it’s organically grown into what it is now. I’d say the faces were based on this little spaceman character I had, who looks a little bit like a LEGO man I suppose. But back in the seventies there were a lot of little characters with little round eyes and mouths, super simple, no nose or anything. I really loved that look. And so I just went with that. And this is actually even before Adventure Time came out, and then when that came out, people would just say, “Oh, it looks just a little bit like Adventure Time!” [Laughter] But I thought, “Oh, so what, I’ll just keep on going with it.” So that’s where that came from. It’s such a super simple thing that I don’t really have to think about it. It’s not something I focus on too much, so that I can develop the story. I’m more interested in that side of it.

FV: I love that insight because, at first glance, your work looks very flat and two-dimensional. It has a very flat, surface quality to it. But you pointing out the idea of Mexican ceramics, or LEGO figures, or like little old robots, that makes me understand the way your work is actually very 3D in its own way because the characters themselves are almost molded or modeled in that way. It’s very different.

Wenlock: Yeah. Exactly that. It’s the 2D-ification of 3D elements. Yeah.

FV: I know that Tsunami is only coming out now in North America and around the world, but I know it was a little while ago that you finished it. So I’m wondering, are you working on new things? Can we expect some other graphic novels from you in the near future?

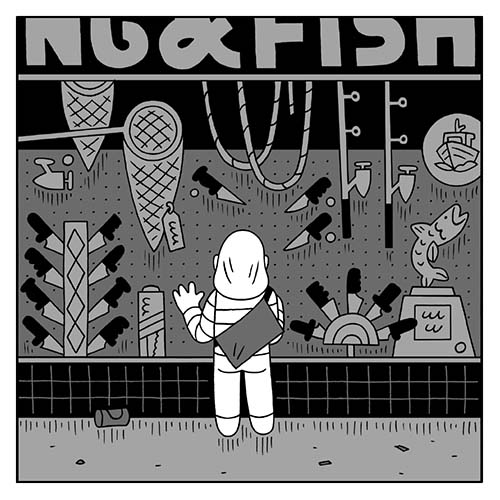

Wenlock: I would love to do another graphic novel. Just right now I’m doing some short pieces, short stories, really just to try and get out of the mindset of Tsunami. If I were to jump into another graphic novel straightaway, I think it would just be very similar to that, and I don’t really wanna do that. I love the format of Tsunami. I love the way the scenes play out. I love working in that kind of format. So whatever I do, I think it’ll be similar to that in terms of the format. But I think the story, I don’t know, I’d like to do something different.

Interview by François Vigneault