Earlier this year, an English translation of Shirato Sanpei’s celebrated tale of ninjas in seventeenth century Japan was published by Drawn & Quarterly. This was remarkable for several reasons, starting with the decades that lay between 1964, when the series first appeared in Japan, and the appearance of a revitalized version for a new audience. Then there was the tale itself, a powerful allegory of class struggles that continue to shape Japanese society today, giving Sanpei’s work a prescience that only great storytellers manage to acquire.

Translators Richard Rubinger and Noriko Rubinger continue to do the honours for Volume Two, which is great news for the many manga readers who hope to see the planned ten-volume work come to fruition. It is a tall ask, but a worthy one, and what we have so far more than justifies the endeavour.

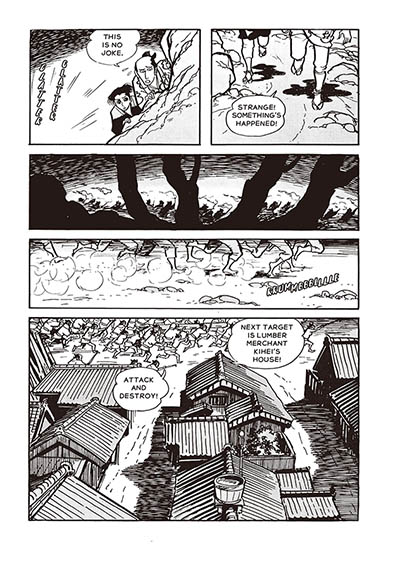

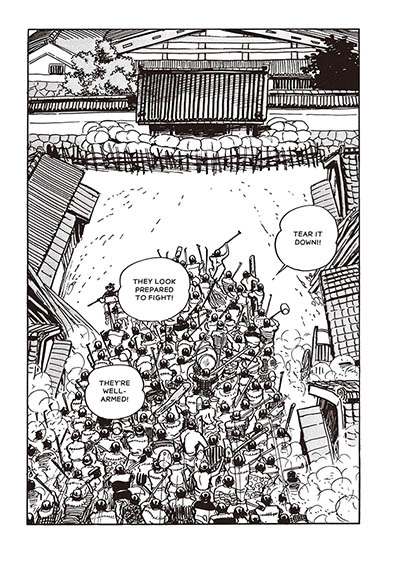

Like all great epics, this one takes its world-building seriously, which makes some demands upon the reader. The cast slowly expands — from the swordsman Minazuki Ukon and priest Unsui to Dojo master Tesshin, all of whom are rendered delightfully. There are minor characters who start to take on larger roles with mysterious purposes, and it sometimes feels as if Sanpei holds all the cards without a clear sense of where they might fall. It is a ludicrous thought, of course, because fans of the legendary magazine Garo are aware of how the original series played out over seven years.

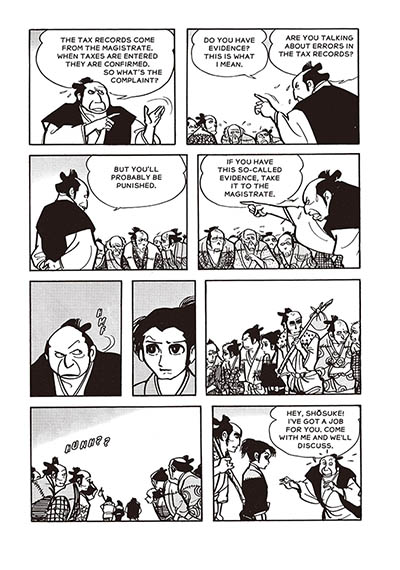

It is difficult to comment on the action, or do more than paraphrase how the narrative evolves, if one isn’t familiar with what has gone before. Avoiding all spoilers, then, all one can say is that a low-ranking ninja (or genin) wakes up to the possibility that one’s rank in society can be altered with access to education. It becomes an important revelation when one considers the setting, a time when low-ranking peasants had no land rights in Japan. This is also a great example of how the allegorical elements of Sanpei’s story start to take on significance, as what his characters say about their world evolves into commentary on the state of politics in the Japan of his time.

His was a period famous for daigaku funsō, or university troubles, when an increasing number of Japanese students began to attend university and started to organise themselves. Sanpei, then in his 30s, couldn’t possibly have been unaware of student demands and the forces that were shaping their turn to activism. “Wholesaler, it is better to make money in secret, not out in the open,” says one of the characters, recalling the anti-capitalist protests of the 1960s, fueled by opposition to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty allowing America to maintain military bases in Japan.

At a little over 600 pages, this is not light reading. It demands attention to detail, much of which is rewarded when one starts to recognise narrative strands and wonder how they will unfurl.

When the first volume appeared, there was much joy expressed on manga forums, with readers expressing hope that this new run would reach its ten-volume goal. If the following volumes end up being as immersive as the first two, The Legend of Kamui may well shape up to be one of the finest manga in English for a long time.

Shirato Sanpei (W/A), Richard Rubinger & Noriko Rubinger (T) • Drawn and Quarterly, $39.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira