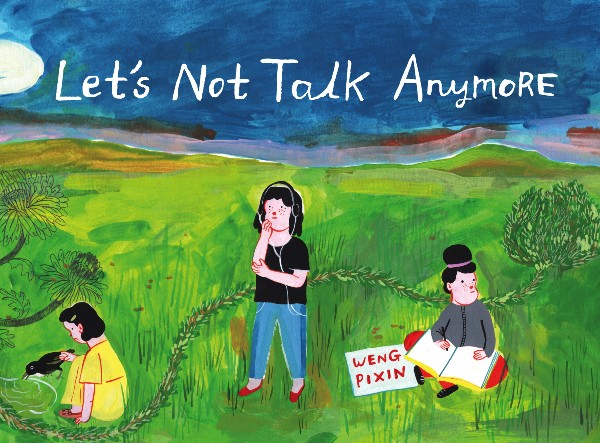

Writing about family is possibly the easiest thing to do, and the hardest. For the artist Weng Pixin, it was an opportunity to try and understand her mother, and the women who came before her. The result, Let’s Not Talk Anymore from Drawn & Quarterly, is a wonderfully nuanced, deeply felt memoir about what it means to be Asian and a woman, in a society that does its best to marginalise these voices.

One of the smartest things about the book is how Pixin analyses her relationships with the women of her family not by engaging with them directly, but by capturing them all (including herself) at the age of 15, then stepping aside to let them share their stories. She speaks of her great-grandmother in 1908, her grandmother in 1947, her mother in 1972, herself in 1998, and even speculates about her own daughter who will turn 15 in 2032. There are surprising threads revealed through this process, along with a shared sadness, an inability to connect, as well as genuine love.

One of the smartest things about the book is how Pixin analyses her relationships with the women of her family not by engaging with them directly, but by capturing them all (including herself) at the age of 15, then stepping aside to let them share their stories. She speaks of her great-grandmother in 1908, her grandmother in 1947, her mother in 1972, herself in 1998, and even speculates about her own daughter who will turn 15 in 2032. There are surprising threads revealed through this process, along with a shared sadness, an inability to connect, as well as genuine love.

For those familiar with Pixin’s debut, the gorgeously illustrated Sweet Time, Let’s Not Talk Anymore follows the same format, down to the dimensions. The colours are riotous, filling out panels that often seem tailor-made for the Instagram generation. We asked Pixin about why she decided to write a memoir, what she expects from an audience, and what she eventually learned about her family.

BROKEN FRONTIER: The ‘seen but not heard’ approach that runs through Let’s Not Talk Anymore also defines gender roles across much of Asia. What prompted you to pay closer attention to this aspect of your own family history?

WENG PIXIN: I think it stemmed from being in this strange middle position I found myself in. My father loves conversations. He loves to tell you stories about his childhood, he will listen to you tell your stories and might ask you a question or two. He has no trouble telling you who he is, what he believes, what he is thinking. Now, when my father wasn’t around, I felt ‘stuck’ with my mother. She was quiet, restrained, very private. She didn’t seem to have any stories to tell. She doesn’t pause to listen to you speak, and she almost never tells you anything about her life. Polar opposites really.

My father’s expressive nature kind of emphasised my mother’s non-expressive, hardened persona. As a child, it is awful but as an artist, I looked at it as an opportunity to discover, to investigate, and to wonder a bit more carefully and thoughtfully about my mother. The more I imagined what her upbringing in 1950s Singapore might have been like: as a child to parents who have even more archaic parenting sensibilities, as a girl, as a Chinese, as the elder sibling to others, as a teenager who loved to draw and paint… this information remained pretty abstract up until I put it down onto paper, and that’s when I see how my mother really missed out on many opportunities to learn the skill and art of communication, how she came from an environment (both familial and societal) that actively discouraged her to find her worth or to express herself, and how she very likely experienced prolonged states of being “seen and not heard”. All of that makes for a pretty bad stew and can really increase the odds of a person to be emotionally unavailable for somebody else.

BF: There is much sadness in the stories of your great-grandmother Kuan, grandmother Mèi, and mother Bing. Do you believe that this, ironically, helped them understand each other better?

WENG PIXIN: I feel, in particular to their generation, it is far more common for their struggle and sadness to remain largely private due to the overall shame that’s attached to the outward expression of anything that’s considered negative. There is this habit of “saving face” over here which I feel really halts any possibility of achieving this beautiful picture you’ve painted here, one where they might better understand each other given their shared sadness. This “saving face” attitude does more harm than good, and one of the major consequences of “saving face”, of very intentionally not allowing a family member see or know your pain in any shape or form, is to lead one to believe they are alone in their suffering, and that no one else in the family can possibly understand their suffering. It isolates rather than creates opportunities for connectedness.

BF: It sometimes feels as if you prefer working with solid blocks of primary shades, and I was wondering if you could talk about how you approach the use of colour, and why you gravitate to certain kinds of shades?

WENG PIXIN: My sense of colours might have come from my childhood history with watching tons of cartoons. I grew up with The Simpsons, Tom and Jerry, Ren and Stimpy, Daria, Pink Panther… to name a few examples, and a lot of these cartoons consisted of bright strong colours. Like in The Simpsons, where the living room is made up of warm pink walls and dark teal floor. When I look at some of the drawings I had made when I was a kid, I could see the efforts to fill a paper fully, leaving very little white space. So… maybe I gravitate towards certain bold bright shades of colours because they look and feel emotionally very intimate and familiar to me.

BF: You once expressed irritation that your work could be perceived as feminine or emotional. Do you acknowledge audience expectations while setting out to create something new?

WENG PIXIN: I think that irritation I had stemmed from earlier years of being disappointed in the lack of community and support in the comics circle here in Singapore… and I really do want to make an effort to move past that hurt, to be honest. It’s a little tricky because it wasn’t an experience that took place within a span of a few years, but it was almost a decade of facing that sort of response or attitude: dismissive in the genre that I am working in. That being said – I do think about who I am writing for in my stories, for sure. I always imagine it is someone whom I respect, and whose positive response to my work would certainly mean something to me. This is to really… strive to be better in the next project, and not fall into old patterns or work within my comfort zones. But I think there is an opposite or ‘twin’ to this thinking too, in that- I try to also not think about audience response in order to express myself and my art without compromising, without editing or diluting any personal artistic vision or goals.

BF: You have, in the past, listed your primary media as mixed media, poster paint, and oil pastels. Has that list evolved over the years or do you still work with the same materials?

WENG PIXIN: I think I used different drawing and painting media such as poster paint, charcoal, oil pastels, ink…when I was in my 20s because I felt it was necessary for me to continue experimenting and exploring after graduating from art college, in order to develop my artistic sense or style. Now in my late 30s, it seems it has become more a juggle of different artistic parts of me. For example, a typical day might be: working on an illustration project in the morning, sewing something in the afternoon, and painting a comic at night. There’s still a ‘mix’ in some sense, but it is not really a mix of media within a single artwork like it used to be.

Buy Let’s Not Talk Anymore online

Interview by Lindsay Pereira

[…] about Factory Summers, pandemic workflow, observation and analysis, and visiting North Korea; and Weng Pixin about Let’s Not Talk Anymore, family dynamics, cartoon colour theory, and juggling artistic […]