A few years ago, not long after her debut Stone Fruit had won the Lambda Literary Award for Graphic Novel/Comics, and was listed as a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, Lee Lai mentioned working on a follow-up that would involve ideas about anger, as well as the ‘lethargy and tension of long-term friendships.’ After reading Cannon, that comment compels one to believe that the artist had a very strong notion of what her second book was meant to be. She had a plan and went on to execute it.

The result, now published, arguably surpasses any possible expectations. There’s a lot going on in these pages—some of it direct, much of it subtle and beautifully nuanced—because what Lai understands implicitly, as a storyteller, is that relationships can be impossible to define within the parameters of fiction. Real life never plays out neatly, dialogue doesn’t come close to mirroring the innumerable emotions that hover beneath the surface of any conversation, and it’s hard to create a character with which a reader can empathise unless the creator feels it first. It is the seemingly effortless manner in which these challenges are met, and the undeniable skill at work, that makes Cannon a great book.

Consider the premise: two gay Chinese women in Montreal navigating the changing facets of an old friendship, while coping with familial pressures, professional commitments, and the ennui that is so much a part of contemporary living in the West. Cannon and Trish get the most space here, and their relationship is what drives the narrative, but there are other associations at play too, all of which shape Cannon’s personality while helping us understand her better. These subplots — Cannon and her mother, her mother and Cannon’s grandfather Gung Gung, Cannon and her boss, or her colleagues at the restaurant — all come together seamlessly to create a rounder portrait of a woman trying to articulate who she is and what has turned her into the stoic adult she is imagined to be.

It’s hard not to believe that Lai has worked in a restaurant kitchen, given the authenticity with which this chaotic life of dishwashing, meal prep, and casual backroom sexism is captured. There is humour on display in these panels, as well as artistic chops, because of how they pack in so much emotion. Even the careful use of magic realism — the magpies that shadow Cannon and her grandfather — is never heavy-handed, acting as a complement to the larger story rather than a literary device. It all points to a maturity of artistic vision that was evident with Ray and Bron, the queer couple at the centre of Stone Fruit. With Cannon, Lai has seemingly crossed a threshold, stepping into the confident space occupied only by artists and writers who have learned how to successfully marry two divergent artforms.

Interviewed not long after her debut, Lai expressed having a rule for when she wrote characters — ‘no villains, only messes.’ It is one she has taken to heart, and the skill with which she implements it should make us more excited about all her work that is yet to come.

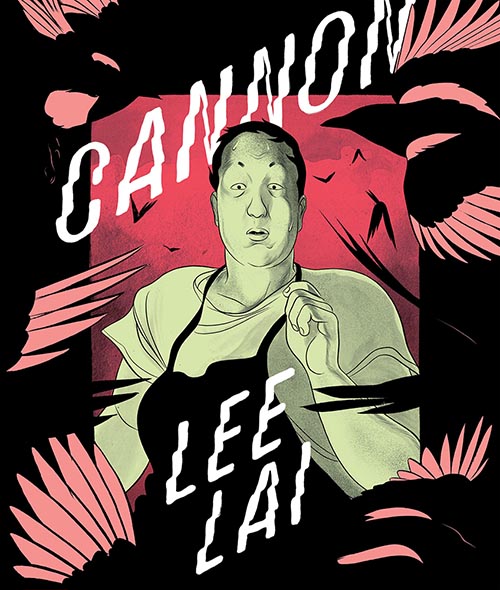

Lee Lai (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira