Sleepless Planet is a long book – 240 pages, if you include the notes and acknowledgements at the end. It’s narrated mainly by Burdock herself, who tells us that “It’s the story of how I healed myself from insomnia over a period of about three years” – but she shares the narration with a koala bear named Kiki. Koalas sleep for about 20 hours a day, so they’re experts on sleep; but they are also an endangered species, and thus representative of the stressed-out relationship between humans and their environment.

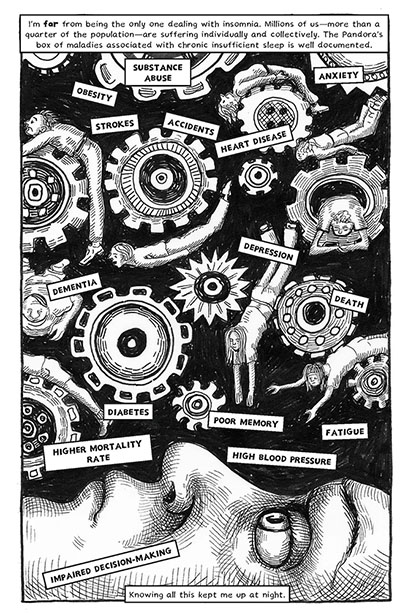

The title Sleepless Planet indicates that Burdock wants to talk not just about her own experiences, but about insomnia as a global phenomenon. She tells us, for example, that over a billion people worldwide suffer from sleep apnoea. There is a linear relationship between the prevalence of sleep apnoea and the prevalence of obesity, and she traces the increase in obesity levels back to a food industry which is constantly pushing us in the direction of super-processed foods and sugary snacks.

Once she began to research her own insomnia, Burdock says, “It was humbling to realize how some of my thinking and behaviors mirrored industrial capitalist beliefs that are devastating on a social and planetary scale. I had this compulsion to be productive…”

The “industrial capitalist” system is geared to profit, often to the detriment of both humans and the environment. Human beings are expected to fulfil twin roles as productive labourers and eager consumers. But the need to be productive, in order to earn more and consume more, drives us towards stressed-out lifestyles. “For example,” says Burdock, “I would compensate for my fatigue with two or three cups of coffee in the mornings… and I relied on a glass (or two) of wine in the evenings, to help me ‘wind down.’”

The book does contain practical suggestions. Don’t have technology in your bedroom. Eat a more natural diet to promote better gut-health. If you’re an insomniac, reduce the hours you spend in bed, in order to increase the proportion of time you spend actually sleeping, and de-stress the going-to-bed experience. To avoid sleep apnoea, breathe through your nose when you sleep, rather than your mouth – the simplest way to encourage this habit is to put a bit of tape across your lips at bedtime.

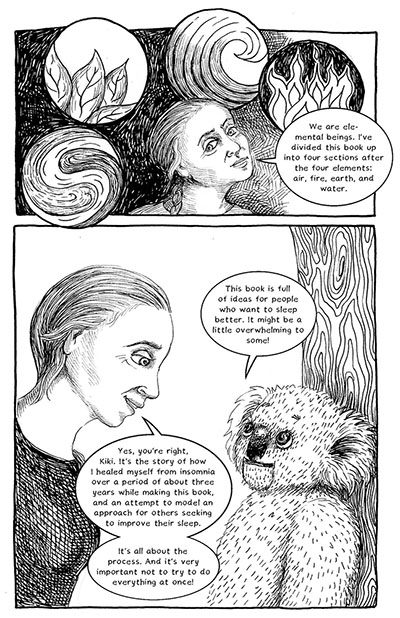

Beyond this, however, Burdock goes into a great deal of background information and philosophising, which some readers may find harder to swallow. “It might be a little overwhelming for some,” warns Kiki the Koala in the introduction. “It’s all about the process,” agrees Burdock. “And it’s very important not to try to do everything at once!”

The book is divided into four sections, named after the four elements – air, fire, earth and water. The first drawing is a full-page illustration of a woman standing on one foot in the Tree pose, with her hands pressed together over the top of her head, and a spiritual light glowing above the tips of her fingers. Straight away we sense that we’re going to be treated to a lot of alternative thinking – tantric philosophy, mythology, folklore, etc – and sure enough, that’s what we get.

Burdock’s discussion of sleep apnoea and good breathing, for example, isn’t confined to remarks about obesity or sellotaping your lips together at night. In order to improve her own breathing she learns how to play the didgeridoo, which leads us into a section about the history of the didgeridoo and how didgeridoos are made. Next she tells us that when her daughter was born her first syllable was “Ma” – “Ma is the fourth Sanskrit syllable in the Kundalini Yoga chant, Sa Ta Na Ma… one of many mantras, spiritual songs, chants, and prayers developed by cultures all over the world that slow breathing down…” She goes on: “As the pace of productivity accelerates, and as social and environmental threats pile up, we’re becoming an increasingly anxious species… There is an opportunity here to stop, pause, and relearn how to breathe [by] doing the things that require conscious breathing, such as chanting, singing, playing the didgeridoo, or meditating.”

If you come to Sleepless Planet hoping for hard-and-fast solutions, you might find this kind of digression frustrating. And in terms of its visual design, there are sections where the book creaks because of the amount of information it’s trying to convey. Numerous experts appear as “talking heads” to spout extracts from their writing. There are sequences where Burdock discusses her ideas, either with a medical practitioner (one called Dr Radiant in particular) or with Kiki the Koala, for several pages at a time, with neither of them doing anything except emit big speech-bubbles full of text. At these points you start to wonder whether Sleeping Planet really needs to be a comic book, or whether it wouldn’t be better off as plain old text.

What it gains from being a comic book, however, is the ability to mix together personal experience, practical tips, research, history, mythology and philosophy with an unconstrained hand. Burdock’s best drawings tend to be the ones which lean towards symbolism rather than realism, and they tend to accompany the more philosophical parts of the book. There are sections where the design achieves a richness and complexity which it would never have had if it had confined itself to hard science and practical guidance. And the real value of Sleeping Planet lies in its attempt to analyse insomnia as a symptom of our ailing civilisation. It may be overlong, but it leaves us with plenty to think about.

Maureen Burdock (W/A) • Graphic Mundi, $27.99

Review by Edward Picot