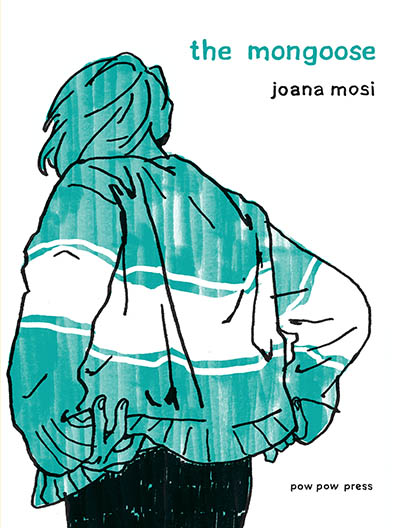

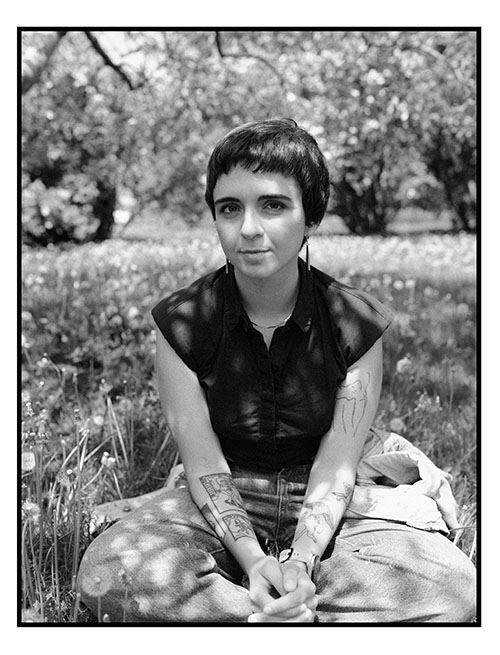

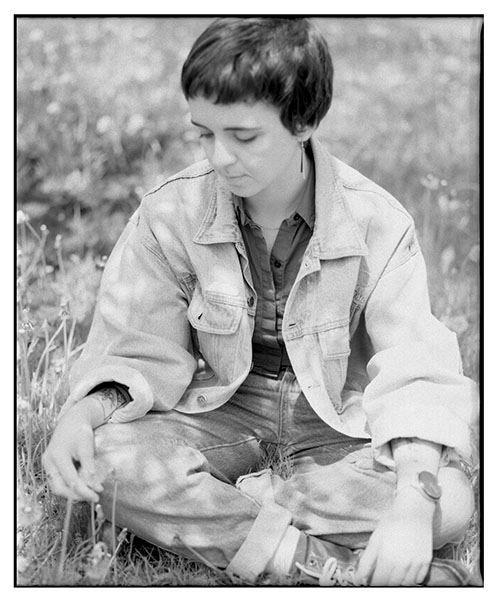

In her native Portugal, cartoonist Joana Mosi is an award-winning creator and a well-known part of the burgeoning Lisbon comics scene, but her comics work has been far less available in the English-speaking world. That is about to change with the upcoming publication of her graphic novels The Mongoose, out this week, and Physical Education, which arrives in April 2026. Her striking, post-modern comics are already garnering attention, with Paul Gravett calling The Mongoose a “formally experimental yet powerful affecting narrative” and Comic Book Herald describing it as “in the conversation for best of the year.”

Recently, Mosi sat down for a video chat with fellow Pow Pow creator François Vigneault to discuss the Portuguese comics scene, her circuitous development as a creator, and her unabashed delight in watching her work take on a life of its own in readers’ minds.

François Vigneault: The Mongoose is going to be appearing very soon. How does it feel for it to be coming out in English?

Joana Mosi: Actually, it’s quite nice. It’s a teenager’s dream, I guess. When you come from a country that doesn’t have English as their main language, publishing comics in English is like a dream, because all the comics that I read as a teenager are mostly in English. Not everybody speaks Portuguese, so obviously for me it also means that the comic can be read by more people across the world. That’s my hope.

FV: Actually, a lot of us maybe don’t know much about the comic scene in Portugal. What is it like drawing comics there? Do you feel connected with the community?

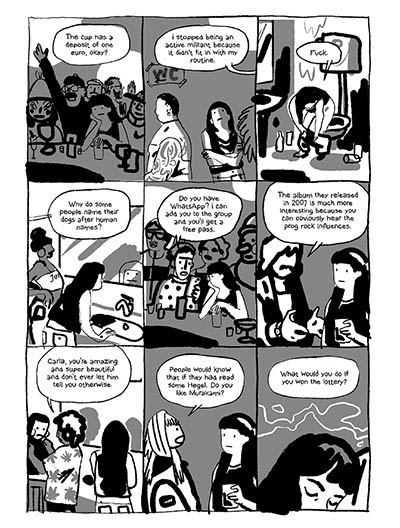

Mosi: Yes, of course. It’s very small, so we all know each other, but it’s quite diverse. I think it’s diverse because we don’t have a specific style; like the French have a specific style, some say Italian as well, and Japanese manga. But in Portugal we are a little bit different, which is a consequence of being inspired by many different types of things that I come to the country. Of course, the closest is French, so like older generations still are very close to the French tradition, but like my generation, we grew up with the internet, and especially American comics and manga. We make all types of things. We love zines and self-publishing a lot, especially because the market, it’s not that promising. So there’s a lot of people just self-publishing and that’s very, very cool.

FV: That’s interesting, because it seems like there’s a space, there’s not as much of a mainstream industry, so there’s more of a space for independent voices.

Mosi: There is, of course, an attempt to exist in the mainstream scene. There is a big effort on the part of the publishers to make it a mainstream scene, but I believe for that to exist, there needs to be more readers first. Comics are still hard to sell in Portugal. At least that’s what the numbers say, although it used to be way worse, say in the early 2000s.

I know that in the nineties, before I was even born, so in the nineties, in the eighties, in the seventies, people were consuming way more comics, but they were also imported. I don’t know what happened in the early 2000s, but comics stopped being sold in magazine spots, for example, on newsstands, and that’s where most people used to buy comics. So selling graphic novels, for example, or longer experiences of reading comics in Portugal, is still a struggle. Quite a struggle actually, I would say.

FV: The Mongoose is coming out with Pow Pow, and they are well known for bringing out a lot of Quebec comics and bringing that to a global or anglophone market. But how did you get involved with Pow Pow in the first place? Because I think you’ll certainly be the first Portuguese author, and one of the first international authors that Pow Pow is publishing.

Mosi: Yes. And I think I’m very lucky for that. There was obviously a bit of luck involved in that. We happened to be in the same festival, me and Luc [Bossé, founder of Pow Pow Press], at TCAF in 2022, or 2023? I went to a portfolio review with Luc, and I came to it with the finished comic of The Mongoose, or at least a version of it, because it had a lot of transformations before it was published. Luc and I met in a portfolio review, and in the same weekend, Luc proposed to me to have Pow Pow publish the book. And I was really happy, ’cause it was not in my plans. I had just signed up because there was a portfolio review and I thought, “Why not? I like Pow Pow anyway.” And I mean, you don’t lose anything by trying. I was very lucky to take that chance, and that Luc noticed me.

FV: I think that that’s great advice. It’s good to just try and put yourself out there.

Mosi: Yeah. I mean, I wouldn’t lose anything. The worst that could happen was Luc saying no. And that’s what happens most of the time. We all know it. I mean, you make comics too, so you know. It’s true. There’s a lot of attempts, and the things that come out are the things that went well. But backstage, there’s all the attempts that sometimes don’t work. And it’s okay. But I still think I’m very lucky.

FV: Let’s talk a little bit about the book, The Mongoose. Tell me, how do you describe it to people? Because you and I previously, we had a little bit of a discussion about how to put this book out there. How do you describe it when you talk to people about it?

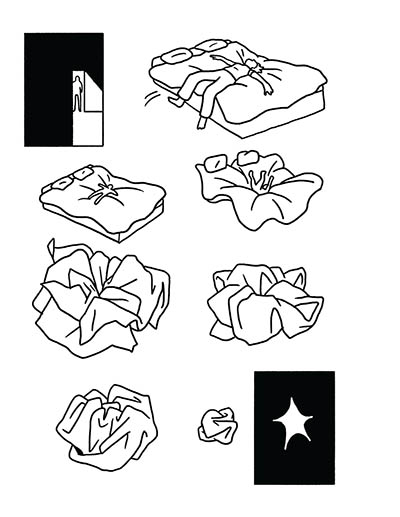

Mosi: Yeah, I think you’ve been a great help to me with that, because I have a hard time describing it myself. I think it depends on who I am talking with, but I would say in a vague way that it’s a book about grief, definitely, but not in the sense of dealing with it. I think it’s more about not being able to deal with grief directly. Now I look back, and it’s been a while since I finished the book, so I have had a lot of time to digest it, and I can look back now and say that the book is about that struggle. It’s about the silence and the lack of communication that arises when you don’t know how to deal with a great loss.

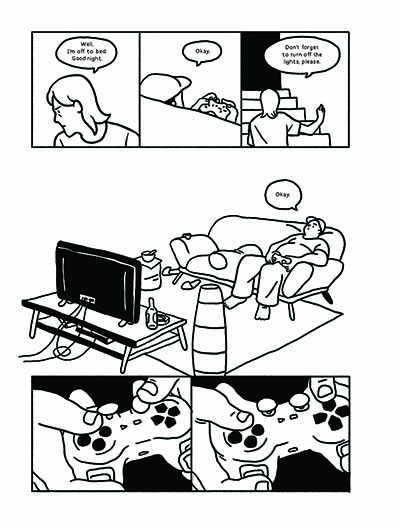

FV: I think that that feeling is clear on the page too. I was just rereading it again, and there’s a real sense of subtlety in the book. Everything is underneath the surface, you know? When you read it for the first time, so much is happening behind what the characters are saying, or like in a corner of the room, and then you read it a second or a third time and you realize that there’s all these sort of clues as to what is happening in the story as you go along.

How did you approach how you wanted to tell the story on the page, what information you wanted to reveal and what you wanted to conceal?

Mosi: I think first of all, I was very close to the theme, to the subject. The idea for The Mongoose came after I lost my dad. My dad passed away, and I realized that the way I was reacting to it was not the way I thought I would react to it.

First of all, when my dad passed away, I knew he was going to pass away, so it was not like a sudden death. And I thought — I think we all think — that if we prepare enough, we will know how to deal with certain emotions. And then the thing happens, and you realize you still don’t know how to deal with it. Because we all struggle to deal with certain emotions in different ways. That’s when a lot of conflicts arise between people. That’s what I wanted to go into with The Mongoose. The book has different characters, and somehow all of them have lost something. And we might think superficially that situation will unite them, because they all have to deal with loss. In fact, it’s usually the other way around, because not all of us process loss the same way. Sometimes that actually provokes the opposite of what we want. People, instead of being more united, they just antagonize each other, because we feel lost, we feel lonely, we feel misunderstood.

That’s what I wanted to explore in the book. I was not looking for a story that would suit me, or make me feel better. I was just curious, like, what is going on? Everybody has to go through this, and I want to explore that side of grief, which is not navigating it at all, it’s the avoidance stage of grief, or denial, I think.

FV: Absolutely. And exactly as you’re saying, you’re exploring something that is by its nature extremely universal. That feeling of loss, of being broken, of something that is missing in our lives, everyone is going to go through that. They’ve either gone through it in the past or they’re going to go through it in the future.

Mosi: Yeah. Sadly. Or hopefully, I don’t know.

FV: Well, it’s sad, but it’s also, it’s real, you know, so both.

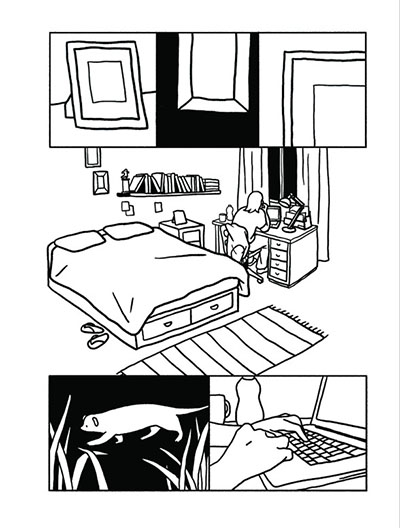

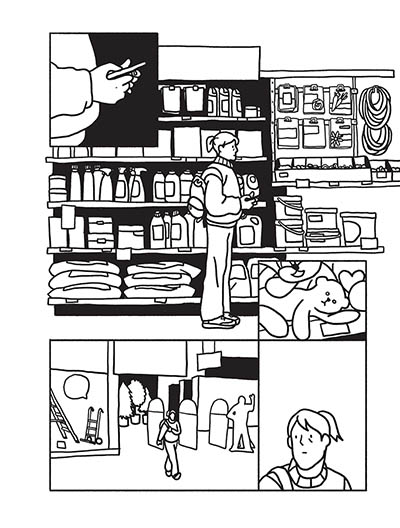

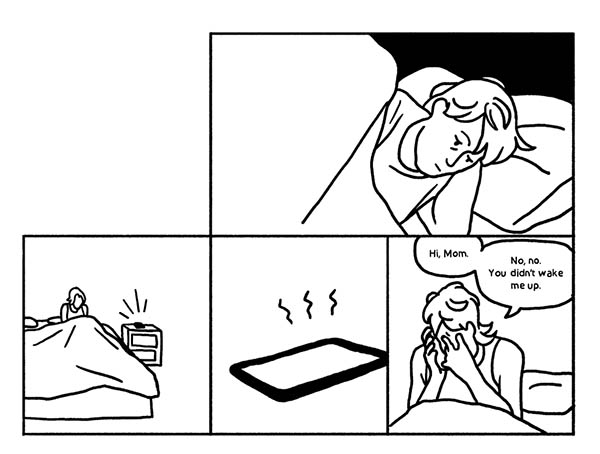

I was just going through the book again, and I was noticing this visual leitmotif of the frame. There’s dozens and dozens of photographic frames, frames of paintings, that are always in the background, and are often blank. I was noticing how that reflects your story in so many ways, even in the way that you present the story on the page. I think for almost any reader, one of the first things they’re going to notice is that you don’t have a standard grid for your panels. You leave a lot of empty space, and negative space. Can you talk a little bit about the idea of the frame, and how you develop that theme in your work?

Mosi: Oh, that’s a really good question actually. I’m glad you noticed the frames. I came up with them in the beginning when I was sketching the pages, and the frames were going to be filled with pictures. The pictures were a very classic way to show, “Oh, this was the past.” Then I realized it probably would make more sense to have nothing in there, because the past is implied in every discussion, in every interaction between the characters, I don’t need to draw it. It’s already implied there, and wanted to leave it, not quite to the imagination of the reader, but to their experience of it all, you know? With the empty frame, we just need to know it’s a memory, that it’s there. We don’t even know which memory. The icon of the frame alone already says enough for me, and that’s why I decided to leave them empty in the end.

When it comes to the paneling, it’s a little bit like what we were talking about before, the isolation that comes with going through a hard emotional experience. For me, now I look back at the two or three years after my dad passed away, and don’t remember what I did. I know I lived them, because I’m here now, but I don’t have memories from those years. It’s really weird. When we process memories, they always become fragmented. Sometimes we can’t face them. So I wanted to put that experience in the reading itself, so the memories also come in fragments, and that means the story is fragmented itself. Also, I like to deal with unreliable narrators. I think Júlia lies a lot. She’s always lying, especially to herself. I enjoy writing, not what is being said, but what is not being said. The true thing that the characters are saying is usually in their tone, and in what they don’t say, or what they seem to be avoiding to say. So the lack of panels, and the fragmented pages, are a visual way to enhance that.

FV: Right. It’s almost as if, in the places where there’s a space on the page, something is happening, but you, the reader, don’t know what it is.

Mosi: Even me, I don’t know! I like that. You know, I studied film for my masters. And my memory is of not understanding more than half of the films that I was watching. That was very frustrating, because all my classmates seemed to really get those films, and I was just like, I don’t know what’s going on. And I remember one classmate told me, “You know, maybe the purpose of the film is to leave you confused. That’s the experience.”

You don’t have to understand everything. Some things are not meant to be understood. They’re meant to be experienced. They’re meant to provoke another type of emotion. And sometimes the reaction is to try to figure out a puzzle that’s not meant to be figured out. Sometimes I don’t have the urge to leave everything explained. People find the explanation themselves. That’s something I take a lot of pleasure in. Sometimes readers come to me like, “Oh, this page meant this.” And I’m like, “I guess it does now!”

FV: They’ve made it mean that.

Mosi: Yeah. That’s the best part of making the book to me actually, is that people make it their own, and that it’s not mine anymore.

FV: That’s quite interesting because I would say that you’re definitely coming from a sort of experimental or maybe a postmodernist point of view, as a writer and as a creator. And many people will think about that as being cold, or like there’s a wall that’s in the way of the audience. But actually, the way you’re talking about it, it’s more of an invitation. You’re inviting the audience to meet you halfway, and do part of the work of the creation as well.

Mosi: Definitely. I know it’s not obvious though. The Mongoose is not my first book here in Portugal. It’s my first book being published internationally, and my first big book, I would say. But I made short stories before, and longer forms that were not graphic novels, and I had other books before. In particular, my first project, in 2016, was a completely different type of language. It was a more classical comic, I was reading other types of things, and of course my influences were different. And when O Mangusto was published in Portuguese, a lot of people were confused. They were like, “Um, what is going on?” A lot of people saw it as a downgrade from the things I did before.

FV: Oh, really?

Mosi: Yes, yes, yes. Obviously, of course! And I’m not offended. I think it’s all right. I think we don’t have to like everything, but I’m interested in exploring this other language now, and I realize the things I’m doing right now, like that are not published yet, they’re a bit more illustrative again. They’re way more classical again, and way more, I would say mainstream. I think that’s the beauty of comics, too. It allows you to use different languages, and different ways of paneling, drawing, and to consider drawing as a type of language that has many different ways of being explicit or not. And that’s okay.

FV: Speak more about that, the way that your artistic practice is changing or developing over time. Do you see it as linear, or do you feel yourself being pulled in different directions? And maybe what pulls you in a different direction with one book versus another?

Mosi: That’s, that’s another good question. I ask myself that every day. Sometimes I think it’s linear. Other times? I think it’s not. I am definitely a sponge. I’m very, very spongey, in the sense that I know if I get obsessed with something, that is going to be reflected in my work, whatever it is. Sometimes it’s an album, sometimes it’s a film. Sometimes it’s a species of frog. Sometimes it’s another comic. And that definitely reflects in my work. But mostly what really inspires me to keep working is just asking questions. And obviously the way I have to dismantle the question shows, visually. I never really know how things are going to come out. Sometimes, even most times, I’m very disappointed with what comes out.

FV: Oh, really?

Mosi: Oh yeah. I think most people who draw, they’re very critical. That’s why time is a good thing. Sometimes I look back at things that I made five years ago and I’m like, “Not bad!” I remember at the time I was just like, this is so awful. And then years later, yeah, it’s not so bad. And sometimes it’s the other way around, which is worse. You’re like, “Oh, this is nice.” And then a year later, “Oh my God, I can’t believe I did that.”

So I don’t think it’s linear. I’ve been questioning if knowledge is cumulative. I don’t think it is anymore. I think it can be, to a certain extent, but I think knowledge is like an organism that evolves. I think every year I think differently, and there are things that I used to believe that I don’t believe so much anymore now. So I like to see my practice the same way.

FV: And how are you feeling about your place in your creative practice right now? Are you feeling good about it, or in the middle, or…?

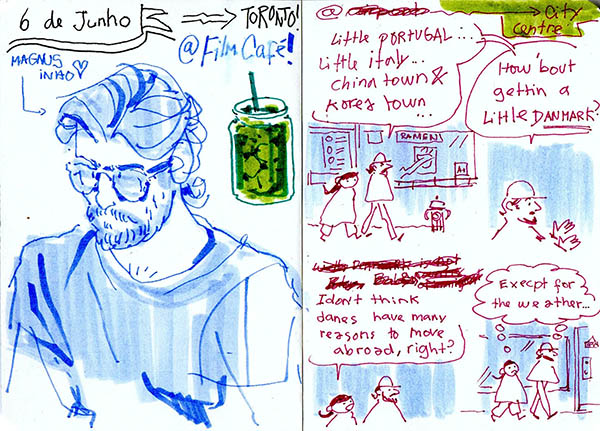

Mosi: Depends on the day of the month, I think. I think I’m stable-ish, which is not a really good feeling. I think I became too comfortable, and if I can be really honest, I’ve been struggling a bit ’cause I’m trying to sketch again. I lost my ability to sketch, and I’m trying to sketch again. And that’s why the daily comics are a good exercise for me.

FV: Right. I’ve seen some that you’ve done. Well, can you talk a little bit about your process? Do you draw in an analog format, on paper? Do you draw digitally? What’s your process?

Mosi: Depends on the type of project. For graphic novels specifically, I like to thumbnail digitally, because it allows me to move things around in a more organic way. Because when I thumbnail, I don’t do it page by page. What I do is I open all the pages at the same time, and then I place things where I think they should be. I make a puzzle. And obviously to make these puzzles, it’s easier to do it digitally than on paper. But if you ask me, honestly, I’ll always prefer to draw on paper. I’ve been becoming too digital. That’s something I’m trying to change, and it’s been really hard. But my daily comics, my sketches, they have to be on paper. They don’t feel natural digitally. Even though I have all the tools. I have Procreate, and the Wacom tablets and all, but I do like to draw on paper still.

FV: There’s something about the reality of it that is connecting, or grounding maybe for you.

Mosi: Yeah, yeah, of course. And that’s how I started as a kid. So it still feels like play, you know? It has to be fun. Otherwise there’s no point in doing this.

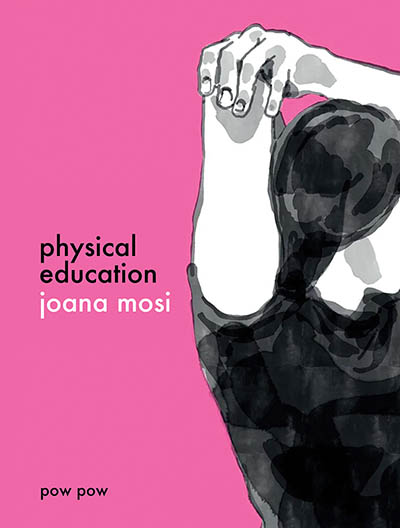

FV: Looking a little bit into the future, The Mongoose is coming out very soon, but we are very lucky that in English, we’re going to have your next book, Physical Education directly afterwards in 2026.

Mosi: Yes.

FV: Can you talk a little bit about that, and what readers can look forward to in that book? Maybe compare and contrast it with The Mongoose.

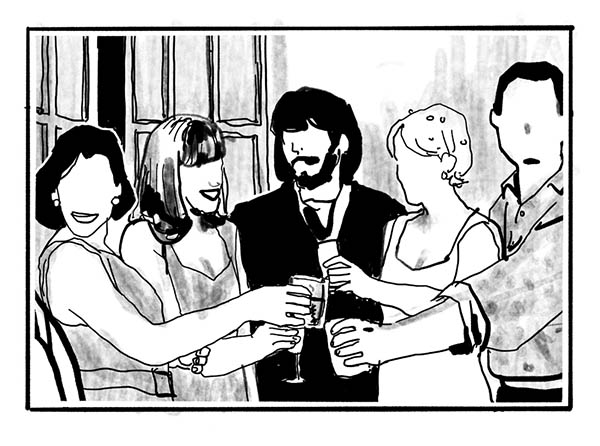

Mosi: Physical Education has already been published in Portuguese, so there’s already some feedback about it in Portugal and from the readers. I can tell you that I don’t think it’s a harder book. But I do understand that if The Mongoose has a more closed narrative, Physical Education is a bit more scattered, there’s not a clear narrative to it. So for some people that can be a little bit of a struggle. But in another way, it’s a more illustrative book. I paid more attention to the drawing in this one, or at least I had more fun drawing in this one.

The theme was supposed to be different, but it still touches a lot of ideas that were worked on in The Mongoose. For example, grief is implied, and there’s also the struggle of going back to normal life. There’s also still the same type of play between panels and layout in the page. The main character is a young woman, just turning 30, and we go with her through a week, where technically nothing really happens. And weirdly enough, the book is about that.

FV: You’re finding the spaces within everyday normality, and the mundane world, and then what makes it special in a way, I think, right?

Mosi: I think it’s more like what makes them not special at all.

FV: Oh, really?

Mosi: Yes. Yeah, they’re not special. I remember when I was a kid, and I realized that all the movies and stories that I read, the stories happened because something amazing happened, you know? There’s a status quo, and then something happened. That’s what, say, Asterisk was about. That’s the comics I grew up with. So I’m always trying to make comics the other way around. Like nothing amazing is happening, and also nothing amazing is going to happen. And is it possible to still have a story with that?

Of course, you’ve already had a lot of cartoonists who try to go that way. How do you end up making stories, if it’s not because the plot goes in another direction? What else can sustain the narrative? I like to dig into the characters. I like to make them go crazy. And I think what Physical Education shares with The Mongoose is that the main character is somehow lost in an obsession, and can’t move forward in their life. And while everything around them seems to keep going, the main character stays still. And that somehow gives you a way into the story, I would say.

FV: What a beautiful way to think about the way your character is moving through the story, and moving through the world. I love that. Well, as a last question, I get the impression that you have a pretty varied media consumption, and that you’re drawing inspiration from a lot of different things. Can you maybe just tell the people what’s something that you recommend that you’ve enjoyed recently? Be it a film, a book, or whatever.

Mosi: Oh, that’s nice. Um, this is random, I was not prepared for this, so the first thing that popped in my mind were TV series. I’ve been watching a lot of series, and here are two different recommendations. The first one is a series called The Leftovers. It’s really nice. The series is not new at all, so probably whoever is reading or listening to this already watched it, but it’s a great show, and I think it’s one of the best written shows I’ve seen ever. I don’t wanna tell anything about it. I think people should just figure it out by themselves. The premise, though, is that in one day, 2% of the population disappears. They vanish. And the show is about people dealing with that loss, which is an unexplainable loss. And you can see the whole world and the whole society going completely crazy because of that, ’cause they just can’t deal with it.

And the other recommendation could be Tiny World on Apple TV. It’s a documentary series about very small animals doing incredible things. It’s narrated by Paul Rudd, who apparently, I learned, also did Antman. So it all makes sense. Tiny World gives you hope for the world, and makes you not step on ants when you go outside the house. ×

Visit the Pow Pow Press site here

Interview by François Vigneault