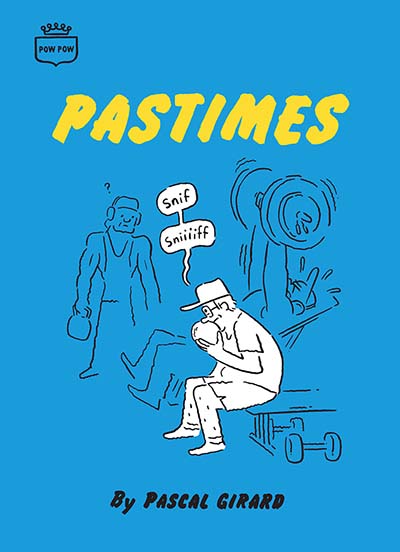

Pascal Girard and Cathon are two of the most distinctive voices in Montreal’s vibrant indie comics landscape, each cultivating a devoted readership through their wry, sharply observed work. Girard is well known for mining (and twisting) his personal life for material, transforming his romantic partner into a freelance detective in Rebecca & Lucie in the Case of the Missing Neighbor and crafting a misanthropic version of himself for Reunion. His recent strips distill the rhythms of daily life into running gags that highlight the quiet absurdities of the everyday with understated humour.

Pascal Girard and Cathon

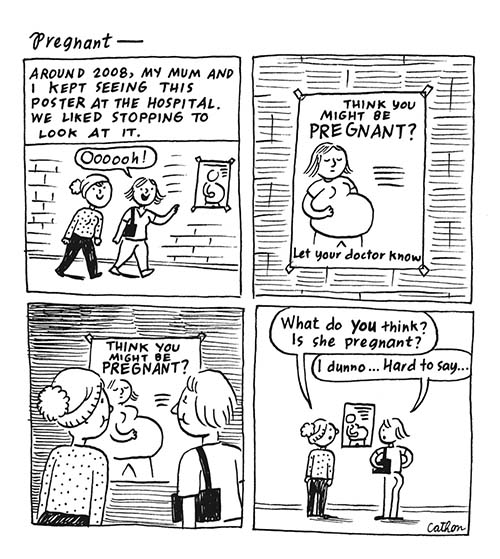

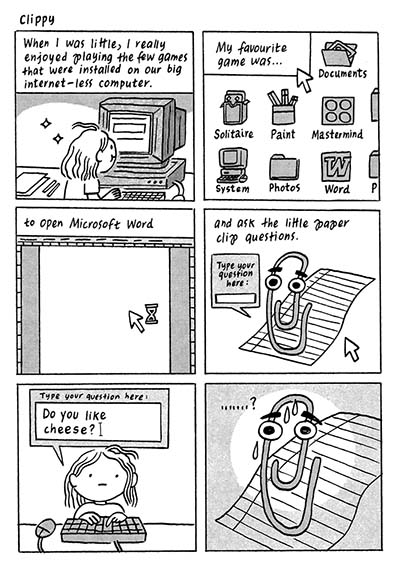

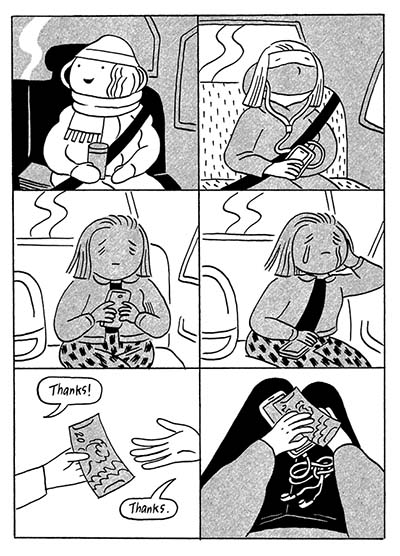

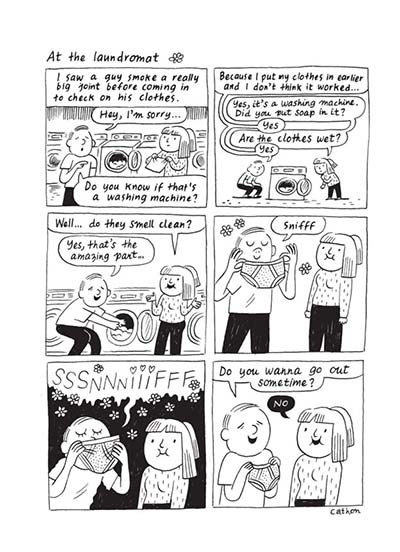

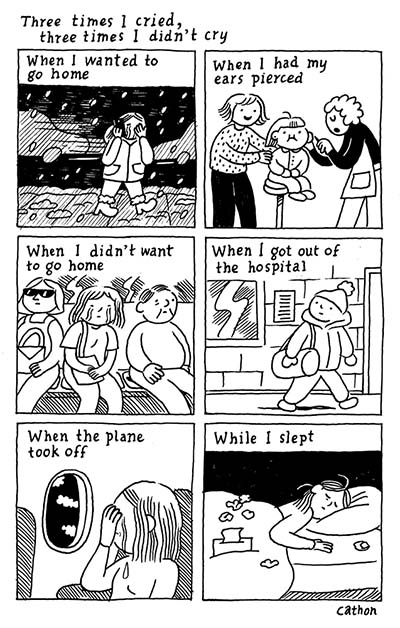

Cathon—whose books include the tiki-murder-mystery The Pineapples of Wrath and the horror homage Vampire Cousins—has long published her autobio strips online, winning a steadily expanding audience for her playful and poignant comics that capture fleeting moments of connection, awkwardness, and delight.

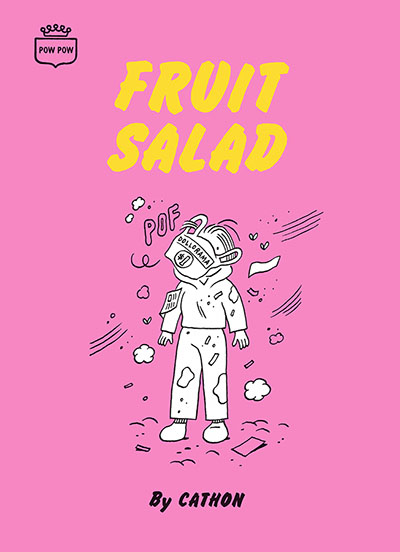

Now, with the simultaneous release of their strip collections Pastimes and Fruit Salad from Pow Pow Press, these two beloved creators are reaching a brand-new audience. In this conversation with fellow Québec cartoonist François Vigneault, Girard and Cathon discuss the strange magic of translation, the inspirations behind their work (including many curious encounters with strangers on the street!), and why the humble comic strip remains one of the most intimate and revealing forms in comics.

François Vigneault: Your books, Fruit Salad and Pastimes, recently came out in English. How does it feel to have these books available to English-speaking readers?

Pascal Girard: It’s great. I’m happy about it because I have quite a few of my books out in English already, so I had some people asking me if this book was coming out, too. Everytime I put the strips online people would say “Oh, you should put them up in English, too,” so finally, they will be out there, and that’s great. The more readers the better.

Cathon: Yes, I agree. I find it a bit amazing when a book is going to connect with an English-speaking audience. It’s a bit invisible to us, I think. Say at a book fair in Québec, there aren’t going to be many people I meet who have read my books in English, but I know it happens. To me, the translation is a bit like magic. When I receive a new version of my book, it’s like I’m rediscovering what I wrote. When I reread my book in French, I don’t necessarily think, “Ah ha ha!” But when I read it again in English, I rediscover the jokes I made. It’s a bit like someone else wrote them. I find that really fun.

Vigneault: Both books are collections of comic strips, drawn from your daily life, about the quotidian. Why were you both interested in exploring this aspect of life, and also why in this format of funny comic strips that are one or two pages long?

Cathon: That wasn’t a conscious decision. I think that this is the form of comic that I’ve been doing the longest. As a teenager, I started doing little strips… It happened quite late, though. Before that I was drawing, but I was too much of a slacker to make comics because it took too long. When I started making comics, they were mostly little anecdotes that I had written down. I would show them to my friends, just for fun. It happened really naturally.

For me, it’s almost like keeping a journal, or reminding myself that a friend said something funny to me on the street, and the most fun way for me to record that is to make comics. Of course the format, at some point, was transformed by the arrival of social media. It’s adapted to Instagram, which has really changed my practice a bit, but otherwise the goal is to remember what happened, so it’s still the same.

Girard: My answer is pretty much the same as Cathon’s. I’ve been doing comics for a long time too, and I think the strip is the most natural or easiest format. I draw these strips in notebooks — I have one here — and there’s something very natural about drawing what I see, or recording what’s happening around me. Also, when I am working on other projects, they are much longer, sometimes it takes years to finish a book. So there’s something about doing the comic strips that gives me a bit of a break. It keeps my spirits up. There’s something satisfying about it because it’s finished quickly.

Doing autofiction, or autobiography, or even sometimes veering towards fiction, but always with me as the main character, it’s a bit easier. It’s something I can do without thinking about inventing new characters or things like that. There’s something comfortable about the method, and the format is less restrictive. And from there, it can go off in other directions: Some things are completely fictional, and other things are closer to the truth.

Vigneault: The way you phrased it, I find that interesting, the way it is like a mixture of an artist’s sketchbook, where you sketch scenes from everyday life, and an author’s notebook, where you might want to jot down your observations about life, but you combine them in a comic strip.

Cathon: It’s really the perfect format for that. Sometimes I wonder, when I started doing these kinds of stories, did I even know what a “comic strip” was? Because as a kid, that’s what I did. Of course I had read them, I read Peanuts and things, but it also seems like it’s a form that comes totally naturally, without being like, “Ah ha, I know that comic strips exist, and so I am going to draw something like that!”

Girard: Right, even a child will do that. I watch my daughter and her friends, and she will tell a story, and she splits the page, sometimes into two, or three, or four panels. And she’ll have her characters, and things she imagines. It’s the same as what we are doing.

Vigneault: Like a universal language for stories.

Pascal, you have been using your own life in your art for a long time, in several other graphic novels, and you use it in different ways, from stories that seem very close to autobiographical reality, but others that elaborate reality a little, bringing in elements of other genres and things. Maybe it’s an obvious question, but why do you find that you always find inspiration in your own life, and this mix between life and art?

Girard: Ah, I don’t know where it comes from. Maybe it’s that when I started making comics, it was like the easiest way! But also, I’m drawn to stories where not too much happens. I will sometimes read a book that’s more adventurous and a little more fantastical, but ever since I was young, when I thought about comics, or movies, or things like that, it was always pretty much rooted in what I experienced, or what I saw, or what people did. And when I started doing comics, there were a lot of people who were making those kinds of stories, too.

I think that’s all mixed up with the idea of the notebook, it became a language that is pretty rooted in, you know, in the square kilometre where I live.

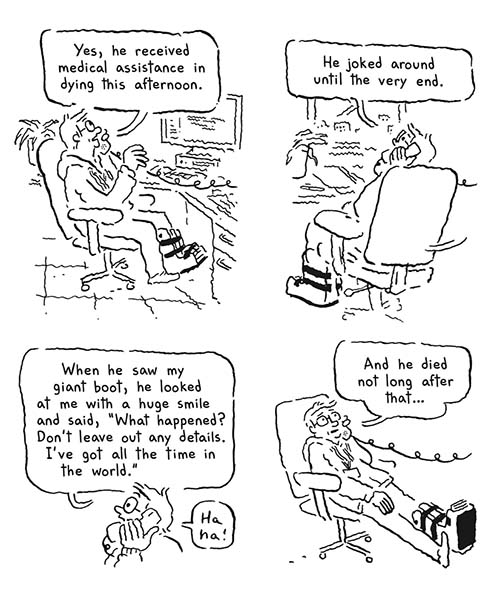

Right now I’m working on a book that’s completely fictional. It’s completely detached from my personal life, but it is inspired by my work at the hospital. So it’s still something that’s close to me, and I know what I’m talking about because I’ve been working there for a long time, because the characters in my book are the kind of people I know, and I set it in places that I know well.

I don’t know, I think it’s comfortable. Sometimes I’d like to get out of my comfort zone and invent something, but it might be be difficult. Well, maybe not so difficult, but I wouldn’t know where to start.

Vigneault: Cathon, one element of Fruit Salad that struck me this time was the mix of comics. There are lots of humorous strips, but from time to time, the book is punctuated with a strip that is a bit more contemplative, or even a little sad, in the midst of things that are more absurd. What inspired you to put several kinds of stories in the same book, and how do you balance these different emotions in the strips?

Cathon: That’s a really good question. I think sometimes it starts from a place where I want to do a strip, but nothing has necessarily happened to inspire one. I haven’t heard someone say something funny, or anything like that.

I like to draw from my own life, taking images that I have in my head, and then I might make a list, or put them together in a way that might be a bit sad, or at least it’s not funny like the strips are… It’s like another kind of mode. Say I want to talk about my summer, I’ll make six panels, and share six moments of my summer, but it’s not going to be like, “Dear diary, this summer I did such and such.” It’s a little looser than that.

But even when I do the humorous strips, of course they are funny, but the mood in those strips isn’t solely humorous to me. Sometimes someone says something, and it really is funny, but for me, there’s an element in it that can make me a little sad too, or bittersweet. So I don’t have the impression that I am completely changing my tone when I do comics that are less than 100% humorous. I find that it can be quite moving, you know, my interactions, it will be funny, but also something more… I don’t know how to explain it, but I can often have both emotions at the same time [laughter].

I’m pleased, because I feel like they all fit together in the book. When I actually put the strips together, some of these comic strips that are more like lists, I added them throughout, because I thought it worked well, it changes the rhythm of the reading. I dig that there are both in there.

Vigneault: I think that mix of feelings, that sadness, and joy, and humour, and the irony of life, it’s very present in both of your books. Maybe there’s something about that in the comic strip format itself. As you said, it reminded me of Peanuts comic strips, where there’s often a kind of sadness in the story.

Pascal, for example, you mentioned that you work in a hospital, and several of your comic strips are related to your work, and the people are often sick, or even at the end of their lives. And you approach these subjects with a light touch, but these are very, very deep subjects nonetheless.

Girard: Yes, I think so, that’s right. I agree with Cathon as well, sometimes with a comic strip that’s meant to be funny, there can be different levels of interpretation, it’s not always the surface level. I do try to keep them light, but they sometimes aren’t. And you know, there’s some ideas I don’t draw at all. I have a lot of ideas, and it’s not that I don’t want to do them, but I try to keep a balance, so it’s not too silly or too serious.

It’s true that sometimes at the hospital, and maybe a bit in my comic strips, you laugh to keep from crying. Those emotions mix together, we laugh a lot at the hospital, even when it can make us cry, too. The line is really, really thin. And that can be good. Sometimes you ask, “Is it sad, is it funny, does it make me feel uncomfortable, is it unpleasant?” You have different emotions.

Cathon: Yes, and sometimes I find that while the real anecdote is happening, I have a whole range of emotions. In a lot of my strips, there are strangers who come up to me on the street and talk to me — I don’t know why, I’ve got the kind of face that makes people want to talk to me. They want to come up to me and confide in me about their lives! And when they do, I don’t wanna be like “Uh, bye!” I let them talk to me, I answer their questions [laughter].

But when I think back, I remember, “Oh yeah, that guy, he came up to talk to me, and it lasted half an hour.” And in real life, I really wanted to get the heck out of there! I was feeling uncomfortable, you know, who knows what will happen! But in the end, for the strip, you can just take the good parts, and then it’s like “Yeah, he had four chickens in the trunk of his car!” but as it was happening I was like “When are you gonna let me leave, sir?”

So, it doesn’t make its way into the comic, but I remember all that. It’s kind of bittersweet, but when I turn it into a comic strip, people don’t necessarily know that I was stuck talking with this guy for 30 minutes.

Vigneault: It’s like editing real life, to find that little core that’s absolutely perfect inside the experience. But it’s clear that Pascal also has the same problem as you, that everyone wants to talk to him on the street! There are all kinds of very awkward conversations in Pastimes.

Girard: When I am walking my dog, I end up talking to other people who have dogs too. Sometimes I don’t want to talk to them! Once I was walking the dog with my girlfriend — it’s rare that she and I walk the dog together, usually one of us walks the dog, then the other stays with our daughter — but this time we were together. And during that walk, I talked to four different people, and I knew all the dogs, and my girlfriend was like “What the hell! You know everyone!” I hope I’m not one of these guys who talks to everyone on the street [laughter]!

Cathon: No, no [laughter]!

Girard: There’s a guy who is always walking his dog, and I see him every evening. He’s a character in the book, and really, I like him. Well, I appreciate him… He can be frustrating, too, sometimes, but I see him almost every evening, we always walk our dogs at the same time and he’s one of the people I talk to the most in my life! And we don’t agree on everything, for sure, but he’s a good guy. He loves dogs.

Cathon: And you see him everyday?

Girard: Every day. And there are lots like that, I could name a dozen dogs, and a dozen of owners.

I think in my strips, they are quite reserved. I’m a bit private, even if my comics are about me, I’m a private person. I don’t know if you can get to know me through my strips. People are going to think they know someone else’s life through comic strips, I’m sure that’s true for you, too, Cathon. But it’s more complex than that, because you choose the moments you are going to show.

Vigneault: That’s very interesting, your approach to the subject, and the idea of yourself as a character in the book, who is not exactly like you in real life. Someone that’s separate from your real life, but your audience might be saying “Oh yes, that’s him, that’s Pascal,” or “There’s Cathon,” as a character, but there’s a real human behind the drawing.

There are lots of stories in each of these collections. Is there a favourite for each of you?

Cathon: That’s a really good question, and it’s fun to think about, because often the ones I really like are definitely not the ones that get a lot of comments or reactions on social media, or that people come up to me to talk about. It’s never the same.

I don’t know, it changes over time too. Sometimes I’ll really like one because I’ll have forgotten it, and then I come back to it. It reminds me of the original anecdote.

Off the top of my head, I think it’s in this collection, in Fruit Salad, there’s a strip where my friend was really crying, and I was ordering her some food, and I had to interrupt her to ask her what kind of coleslaw she wanted?

Vigneault: I think that one might be in a future book!

Girard: I don’t know either. It’s a bit complicated because, for me, this book is like a big project, where I did the strips one by one, and at some point I put them all together, to make a book. For me, it’s like a single project.

Vigneault: It’s a body of work.

Girard: It’s interesting to realize the things that make me laugh. And maybe it’s not the same ones that are more popular, like Cathon said. Sometimes I read them again later, and I think “Oh, that’s not that funny at all, ” or it’s embarrassing. But I’m not sure I can pick a favourite.

Vigneault: It seems to me that might be the answer to the question, that it’s a bit impossible for these books. You’re both in the work, it’s like a big project that you continue with over time.

But that also makes me want to ask another question. I noticed that both of you are continuing to post new comic strips on your Instagram accounts. Do you think we’ll be getting more books in these series?

Cathon: I think I’ll have a new one out in French next fall. I probably already have about fifty pages ready. That’s crazy because I made Fruit Salad over the course of seven years, it was something I did from time to time at first. It’s become much more regular. Now, in just a few months, I already have a third of a book, and I can really see that I’ve started to take it much more seriously. Now that it’s something important in my artistic practice.

I think I really derided this part of my work before, like “Oh those are just little jokes, it’s not very interesting.” It was when other authors, particularly other creators at Pow Pow, began to talk to me about these strips, that I realized that it wasn’t just little gags and jokes, that there was a nuance to it. And when I understood that this was noticeable to other people, I thought maybe I could do it more intentionally.

Girard: Me too, I think it’ll be out next fall in French, because I think I already have about a hundred strips finished. It’s a bit like working out, the more you do it, the easier it is. I try to put less pressure on myself about these strips, and in the end, I get almost more feedback on it than on other things I do.

I don’t know, but there’s something pure about it. Like by putting less pressure on yourself, and using a simpler drawing style, you’re getting a little closer to the essence of what’s fun about doing it. Like why did we start doing this in the first place when we were kids? With this format, there’s something about it, it’s fun to read. It’s a little less pretentious, maybe? It’s like a little break.

Cathon: It’s really accessible. A lot of people told me that it was with these strips that got them into comics, because, as you said, you don’t need to concentrate for very long. You can leave it in the bathroom [laughter]!

Vigneault: It’s that format, that little comic book format. It really reminded me of the little paperback collections that I read when I was a kid, things like B.C. and Peanuts. There’s something very warm about it, this way of engaging with a person, you read one comic strip at a time, but you follow the story. It’s very welcoming.

Cathon: I feel like part of it is that, at least for me, with my book, I think people can sense that I have fun making it. It’s really the element of my practice, you could say, that allows me to enjoy my work a lot. Several years ago, I think it was around 2017, I was going through a kind of burnout because I had taken on too many contracts at the same time. I wasn’t doing any of these kinds of strips, or anything just for me. And it took me a while to rediscover the pleasure of drawing, writing, and finding that my ideas were good again. But it really helped to do comic strips for that because you don’t have to think as long as you do for a graphic novel. There’s no pressure, you just do it, and as long as it’s readable, you can share it right away. And I think that pleasure has to come across, too.

Girard: Yes, I’m surprised that more people don’t do strips like these. Often people will say it’s so hard to write a strip, to squeeze it all in, or you don’t have enough panels, I hear that a lot. But for me it’s far less intimidating as a format. When people make a graphic novel, they’ve got a plan for 100, 150 pages, 200 pages, it’s gonna take them 10 years, these big projects! In my head, there’s something so much easier, so much less intimidating.

You end up improving or teaching yourself a little bit, even if the format is restrictive. I hope there will be more strips from creators. Of course, before there were newspapers and things like that, and now, it’s true that with social media and all that, it’s coming back. I mean, I’m an old guy, but 20 years ago, we all did comic strips and single-page comics on our blogs! There’s something a little bit natural about it, I think, for me, and it surprises me there aren’t more.

Cathon: I think of it like a muscle too. If you haven’t developed it, it’s tough to get started. Like for me, if I need to make an editorial drawing, in my head, it’s like I don’t have that muscle, I don’t know where to flex!

Girard: It’s true. You have to build a story, piece by piece.

Cathon: Right, building to a punchline, creating the rhythm, it’s all really important. Because there are really small subtleties that make it work or not, it’s not as simple as all that. There’s really a very precise language that you have to use for it to be effective, and end at the right moment. ×