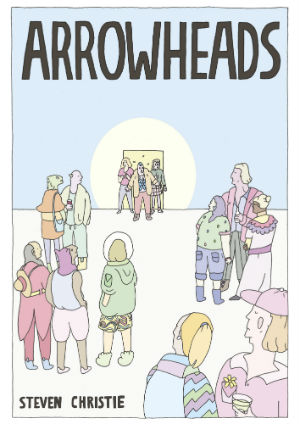

The sharpest satire always comes from satirists who are well versed in the subject matter they are skewering. In his graphic novella Arrowheads, Steven Christie takes aim at the haughty self-important world of fine art galleries and not only nails the broad strokes, but acutely digs into the small details. With his thin wiggly lines and soft pastels, Christie follows three young artists comically trying to fake it ’till you make it, as they gallery crawl from one ridiculous exhibition to next; with each continually trying to find where they stand on the line between the real and the performance of the real.

The sharpest satire always comes from satirists who are well versed in the subject matter they are skewering. In his graphic novella Arrowheads, Steven Christie takes aim at the haughty self-important world of fine art galleries and not only nails the broad strokes, but acutely digs into the small details. With his thin wiggly lines and soft pastels, Christie follows three young artists comically trying to fake it ’till you make it, as they gallery crawl from one ridiculous exhibition to next; with each continually trying to find where they stand on the line between the real and the performance of the real.

Christie quickly introduces the trio of blue mohawked Sam, his cohort Jules, and their bespectacled and slightly farther-up-the-success-ladder friend Stacey. They all meet up at what initially appears to be a crowded gallery opening, only for it to be revealed that the majority of the patrons are holograms. In a clever visual trick, Christie will repeat this aesthetic of having gallery patrons appear in monochrome while our protagonists are rendered in full color through out the book. Both subtly putting into question just how populated these galleries actually are, and hinting at how the trio sees themselves in comparison to the other gallery goers. Christie further sets the scene by contrasting the sparse aesthetic of the gallery walls with the unique and at times otherworldly rendering of his background characters. Their peculiar looks and performances adding a roguish Mos Eisley cantina vibe to our protagonist’s gallery hopping.

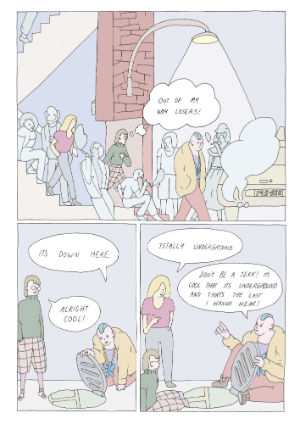

This sort of exaggeration to capture the ecstatic truth of the art-going experience runs throughout the comic. The ridiculousness of an exhibition of ants let loose in a room full of holograms escalates to invisible art inside a gallery beneath a manhole, topped of by another gallery made entirely of ice. Yet to the regular gallery hopper there is as much familiarity to these grandiose but hollow exhibits as there is to the free wine at an opening. We’ve never seen exhibits or galleries this cartoonish, but we have likely shaken our heads and rolled our eyes at something pretty close. Equally over the top are the trio’s run ins with art world gadfly Ryan, who is so committed to the half joking ironic zeitgeist that he has convinced himself that working as an unpaid elevator operator is a form of performance art about liminal spaces.

Ryan isn’t the only one mixing up the line between performance and reality as Sam, Jules, and Stacey soon get roped into a farcical bind by the director of the prestigious Permafrost gallery. When Jules has a shouting meltdown at the ironic insincerity of gyprock propped up against a wall being presented as art, Sam tackles her in front of a stunned crowd. Likely to avoid an even bigger scene, Stacey steps in and informs the audience that they have just witnessed the performance of an institutional critique. When the dog-headed owner of the Permafrost gallery comes over to Stacey to compliment her work, she cannily rolls with the lie in hopes of raising the trio’s cache. Though they secure a spot for a repeat performance at the next opening, it becomes clear that while Sam took Jules’ breakdown as real she tells him that it was all an act. By leaving this and other questions as to the true nature of the group’s motivation unresolved, Christie wisely lets the reader ponder the times they too might have downplayed a moment of honesty for the sake of expediency.

This question of what is real and what is performance dogs our protagonists as they try to come up with what to do for the Permafrost opening. At the gallery Sam runs into an old friend who appears to have become a banker after dropping out of art school, but when he admits that he is still and artist and that his normal life is all an act; Sam’s only advice is to make sure to get proper documentation of the moment when he tells his wife and kids. When a patron disappears into a Super Mario 64 style painting, Stacey wonders if you die inside the painting you die in real life. Neither her nor her fellow patrons seem overly concerned with the answer, instead offloading the dilemma to the artist’s intent. It is telling that most of the trio’s hair-brained performances schemes involve either burglary, or vandalism, or assaulting the gallery patrons. When everyone is ironically detached from reality sometimes the only way to pull them back in is to let loose a swarm of bees.

Christie’s unique aesthetic does much in letting the audience in on the comedic tone of Arrowheads. His squiggly, simplified characters are both charming and inviting. With his choice to frequently show them within a wide angled composition highlighting his strong ability to render their performance. In keeping with their disaffection the characters rarely over gesticulate, yet their emotions are always clear in their facials and body language. And in the rare moments when things do get wildly in motion, Christie does an equally strong job of capturing the kinetics of his characters twisting and falling through space. The largest weakness in his design however is when his panels do not prioritize his inventiveness in character design. While many panels are wisely filled up with the rag tag cast of gallery goers, it is the panels where Christie frames only one or two characters against a mono-color background that his aesthetic feels flat. Their staid performances and simplified designs having to do a lot more lifting to hold the reader’s attention, resulting in some uneven moments when compared with the more lively compositions.

Christie’s unique aesthetic does much in letting the audience in on the comedic tone of Arrowheads. His squiggly, simplified characters are both charming and inviting. With his choice to frequently show them within a wide angled composition highlighting his strong ability to render their performance. In keeping with their disaffection the characters rarely over gesticulate, yet their emotions are always clear in their facials and body language. And in the rare moments when things do get wildly in motion, Christie does an equally strong job of capturing the kinetics of his characters twisting and falling through space. The largest weakness in his design however is when his panels do not prioritize his inventiveness in character design. While many panels are wisely filled up with the rag tag cast of gallery goers, it is the panels where Christie frames only one or two characters against a mono-color background that his aesthetic feels flat. Their staid performances and simplified designs having to do a lot more lifting to hold the reader’s attention, resulting in some uneven moments when compared with the more lively compositions.

Arrowheads is a strong arrival for Christie. The world he creates is vivid and charming, all mixed with his joyous line work and his warmly inviting coloring. He masterfully derives comedy not only by letting the air out of the puffed up world of fine art, but by keying into all the social discomfort and anxiety that comes from being a participant in that scene. The reader laughs because they see the characters as fools, while simultaneously recalling the times they themselves have been fools. The reader can’t help but want to see more of Christie and his softly packaged razor sharp satire.

Steven Christie (W/A) • Power Couple, $12.00

Review by Robin Enrico