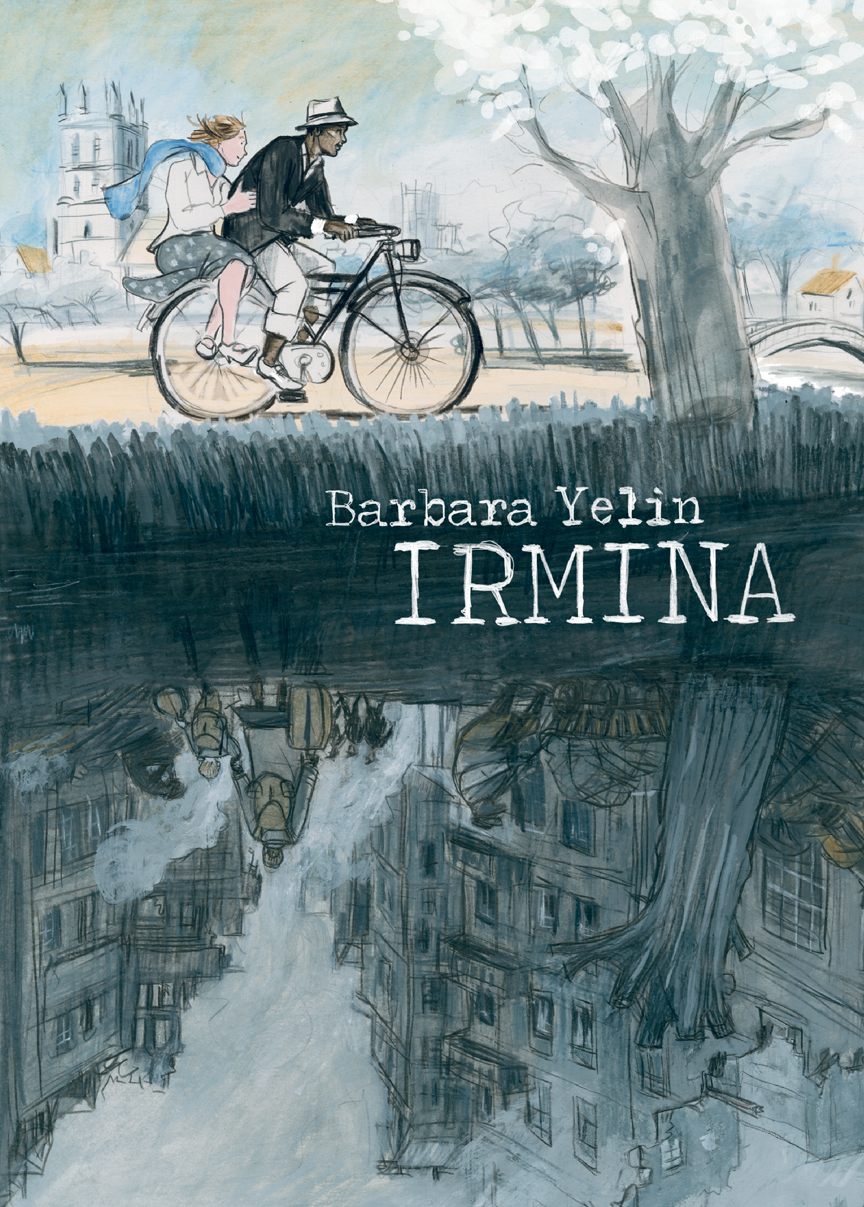

Irmina, Barbara Yelin’s award-winning graphic novel, is a paradoxically beautiful and unsettling piece of work that avoids all the obvious choices to ponder how an independently minded young woman can become complicit with a murderous regime.

Every now and then a magazine show will dust off the old wheeze of staging some sort of incident in a crowded place – the attempted mugging of a child, say – and seeing who intervenes. ‘Have-a-go heroes’ will be celebrated, while there’ll be much tutting and headshaking at those who, for whatever reason, choose not to get involved.

Every now and then a magazine show will dust off the old wheeze of staging some sort of incident in a crowded place – the attempted mugging of a child, say – and seeing who intervenes. ‘Have-a-go heroes’ will be celebrated, while there’ll be much tutting and headshaking at those who, for whatever reason, choose not to get involved.

An altogether weightier version of that investigation has been one of the key historical debates in Germany over recent decades, as a younger generation wonders how much their antecedents knew or could have done to stop the horrors of the Nazi regime.

In Irmina, award-winning cartoonist Barbara Yelin takes a bold personal look at the issue, basing this deeply involving graphic novel on letters and documents left behind by her grandmother. She doesn’t try to come up with a pat answer or an ultimately life-affirming conclusion about the human condition. Instead, across nearly 300 pages, she creates a compelling character study that shows us ‘how’, if not ‘why’.

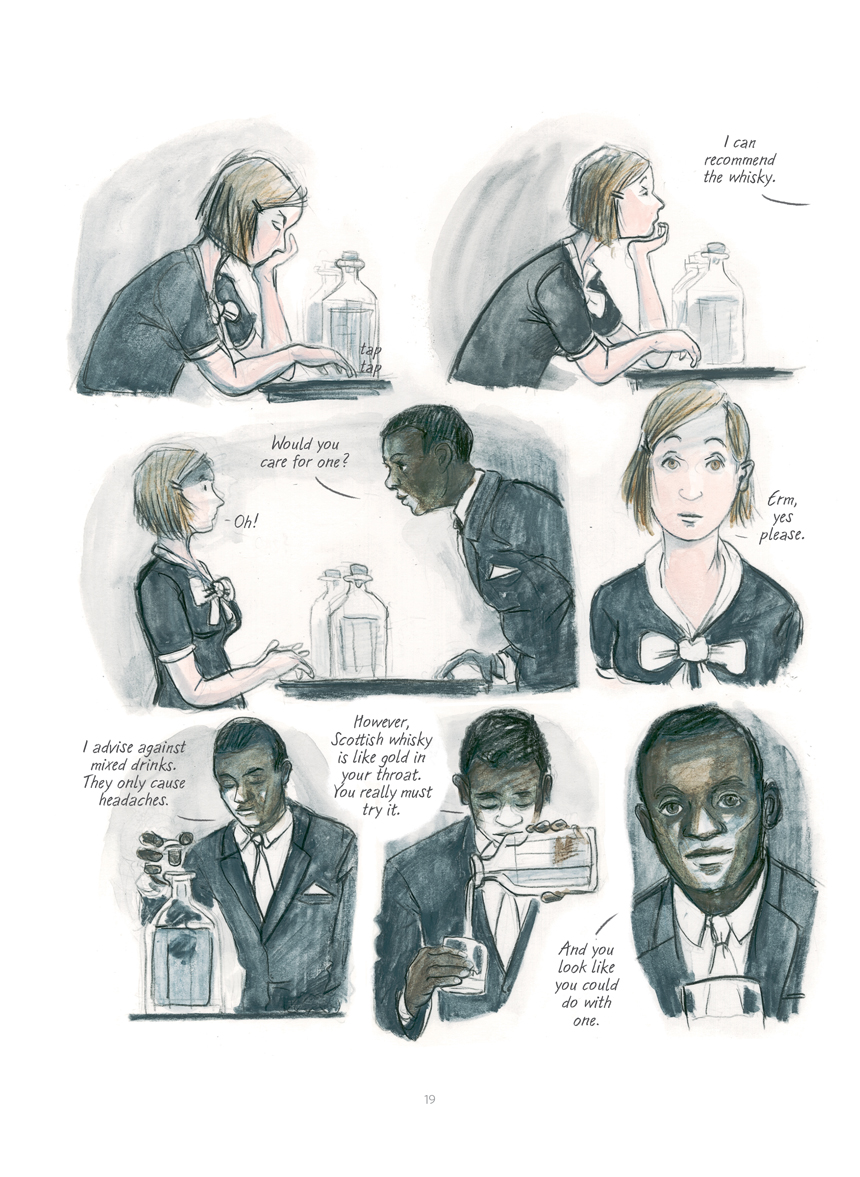

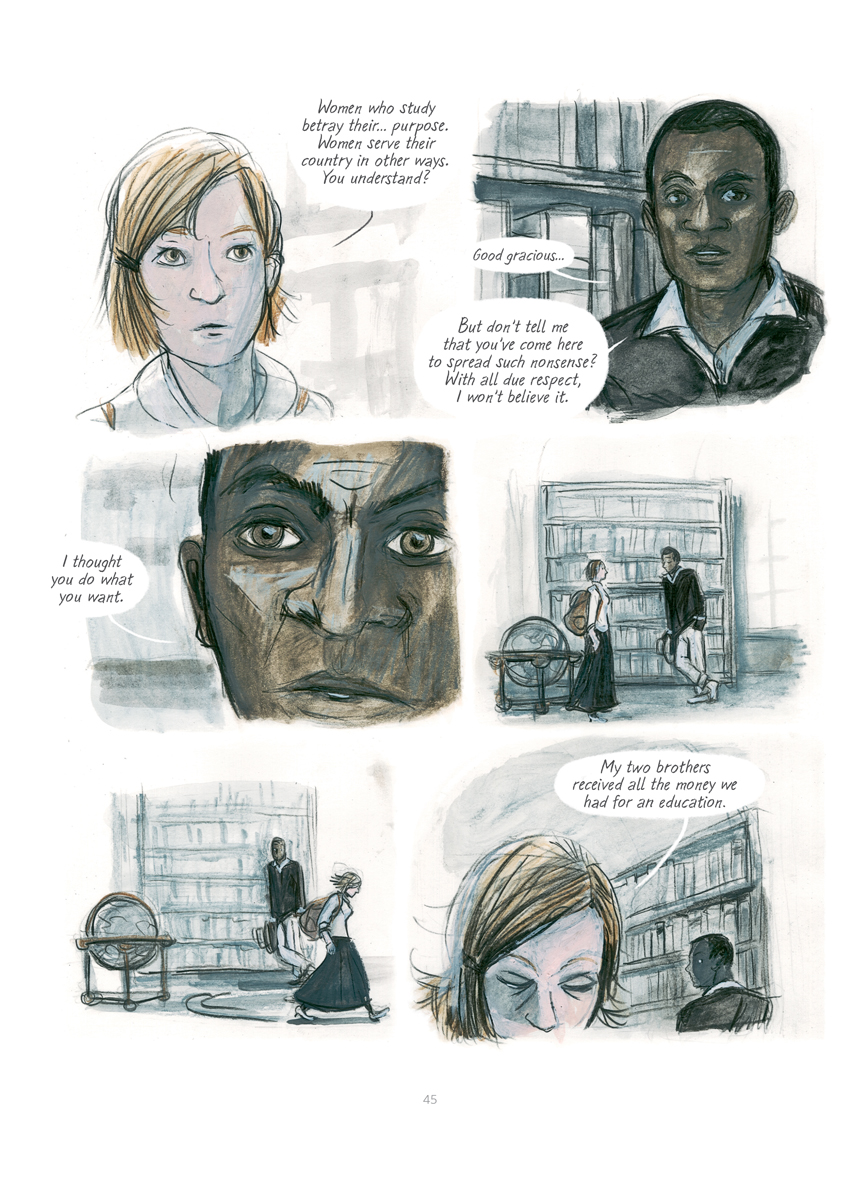

We’re introduced to Irmina as a student making her way to 1934 London, hoping to develop the commercial skills to enable her to stake out an independent life. However, the complexity of Yelin’s creation soon becomes apparent. The determined and phlegmatic young woman we meet displays an intransigence that varies between an admirable strength of will and snobbish disdain.

We’re introduced to Irmina as a student making her way to 1934 London, hoping to develop the commercial skills to enable her to stake out an independent life. However, the complexity of Yelin’s creation soon becomes apparent. The determined and phlegmatic young woman we meet displays an intransigence that varies between an admirable strength of will and snobbish disdain.

When she meets Howard, a black Caribbean student on a scholarship to Oxford, they are drawn together as outsiders. However, events conspire against the couple and Irmina is pulled reluctantly back to Germany, where she soon finds herself drawn into the Nazi orbit. Before long, she’s working at the Reich Ministry of War, happily taking the fruit from a tree left behind by an unnamed “Jewess” who disappeared from a downstairs apartment, and making clear her differentiation between ‘emigrants’ and ‘normal Germans’

However, as her various aspirations are frustrated, Irmina is forced to fix her hopes for the future on an advantageous marriage. When she ties the knot with architect and SS officer Gregor Meinrich, she also ties her fate closer to that of the Nazi regime.

However, as her various aspirations are frustrated, Irmina is forced to fix her hopes for the future on an advantageous marriage. When she ties the knot with architect and SS officer Gregor Meinrich, she also ties her fate closer to that of the Nazi regime.

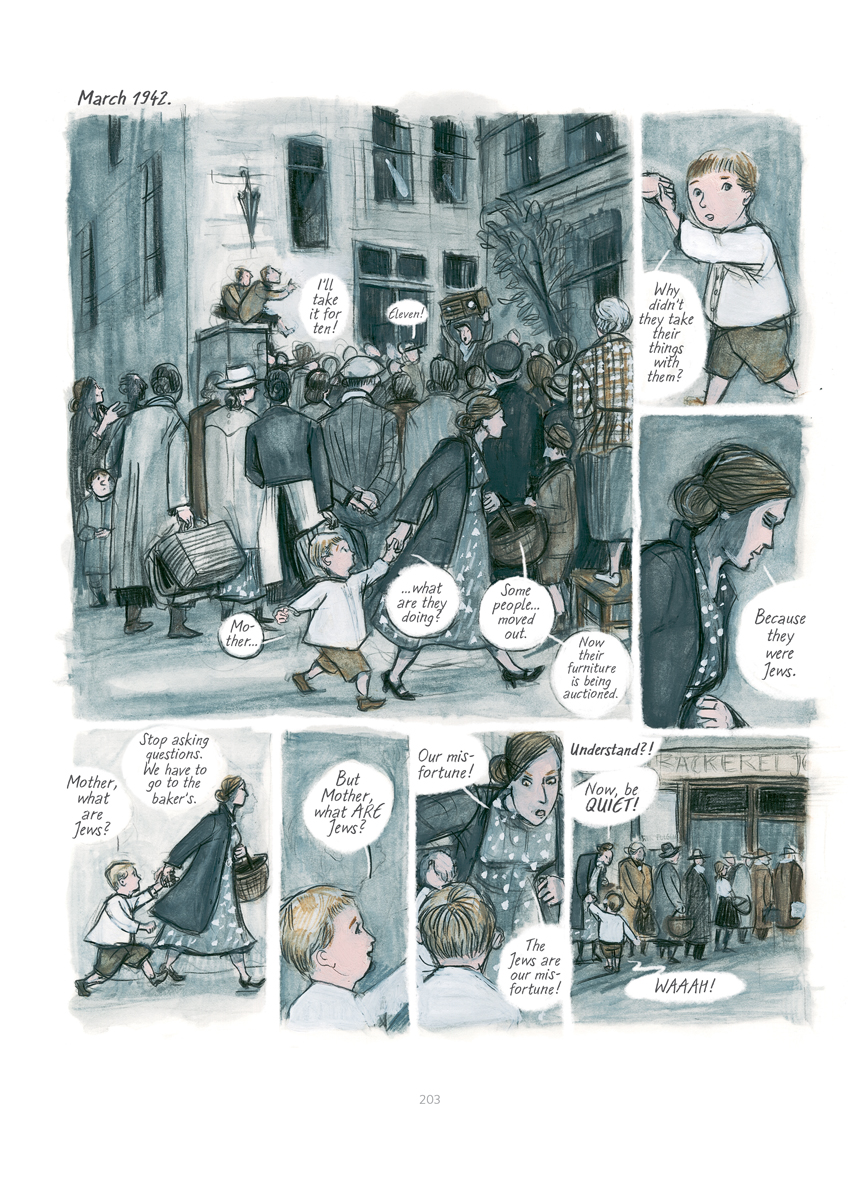

With her ambition for Gregor now her driving force, Irmina finds herself increasingly aligned with the hegemonic viewpoint of the country’s rulers, denouncing Jews as “our misfortune”, and trotting out party rhetoric to anyone whose resolve seems to be wavering amid the hardships of war.

Has she been swept up in a grand delusion or is she being opportunistically complicit? The complexity of Irmina’s character and the dark questions it forces us to ask ourselves show how lightweight most comic characterisation is. (And those questions are analysed at length in a probing and enlightening afterword by academic Alexander Korb, Director of the Stanley Burton Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Leicester)

As the tide of the war turns and Berlin comes under increasingly heavy Allied bombing, Irmina finally has to take her son Frieder and flee to the countryside. In one of the book’s most telling sequences, as she leads the horrified child through the corpse-strewn ruins of the city, she tells him to “Do I what I do, Frieder, and look away”.

As the tide of the war turns and Berlin comes under increasingly heavy Allied bombing, Irmina finally has to take her son Frieder and flee to the countryside. In one of the book’s most telling sequences, as she leads the horrified child through the corpse-strewn ruins of the city, she tells him to “Do I what I do, Frieder, and look away”.

With the American army approaching and the war hastening towards its end, she burns the pile of letters she has received from her husband on the Eastern Front – an act that symbolises the cutting of ties with the past and the selective amnesia of a volk that didn’t want to be associated with the atrocities carried out in its name.

That distancing is seen from another perspective in the third part of the book, which pitches us startlingly from 1945 to the Stuttgart of 1983. Now a veteran school administrator, Irmina makes her solitary way like a ghost through the clean clutter of modern European life. However, the past isn’t done with her yet, and another letter out of the blue leads to a crushing realisation of the weight of history and the snowballing regret of lost opportunities.

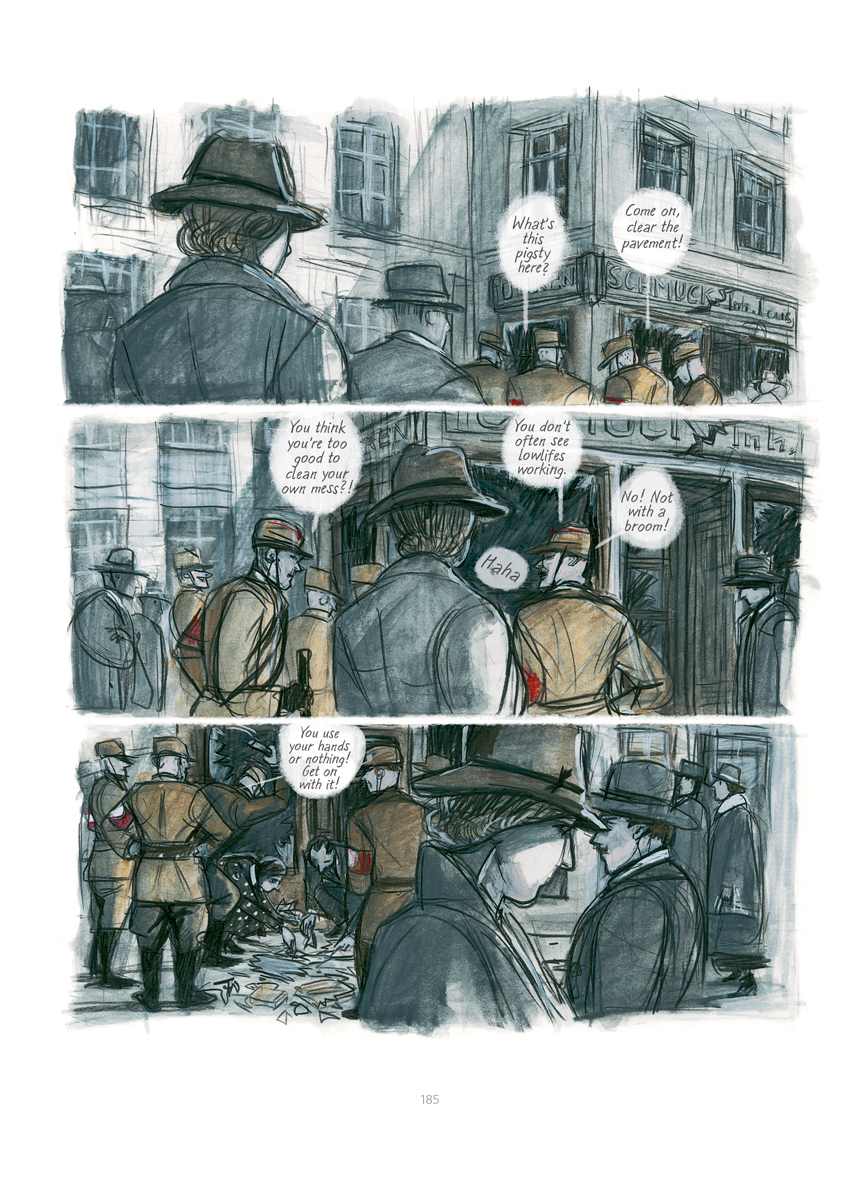

Someone with a better eye for materials could probably describe Yelin’s artistic technique better than I can. However, its apparent mix of pastels and washes give the work a softness that perfectly suits the mid-century smog that envelops the largely monochromatic cities of London and Berlin. That gloom is punctuated only occasionally, most memorably by the red associated with Nazi banners and uniforms, signalling a seductive but dangerous allure. The lack of hard edges also gives the work an easy organic flow.

Someone with a better eye for materials could probably describe Yelin’s artistic technique better than I can. However, its apparent mix of pastels and washes give the work a softness that perfectly suits the mid-century smog that envelops the largely monochromatic cities of London and Berlin. That gloom is punctuated only occasionally, most memorably by the red associated with Nazi banners and uniforms, signalling a seductive but dangerous allure. The lack of hard edges also gives the work an easy organic flow.

From first page to last, Irmina’s driving force is her desire for independence through education and her simmering resentment at the opportunities she was denied in order to allow her brothers to receive theirs – seen at its most touching in her silent observation of a group of free-spirited female students in Oxford. In an era when millions of girls around the world are still denied an education, the frustration and lack of opportunity afforded to Irmina casts a relevant contemporary shadow.

Going into this book, you might expect Irmina to follow the Hollywood path of looking around herself, burning with the injustice of it all and standing up for what’s right. However, one of the many strengths of Yelin’s book is that she never follows the easy path. Irmina is a provocative and often upsetting book, but it’s one that mixes craft and purpose to powerful effect and deserves to be read widely.

Barbara Yelin (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £16.99

[…] Irmina by Barbara Yelin […]

[…] https://www.brokenfrontier.com/irmina-barbara-yelin-selfmadehero-self-made-hero-graphic-novel-review/ […]