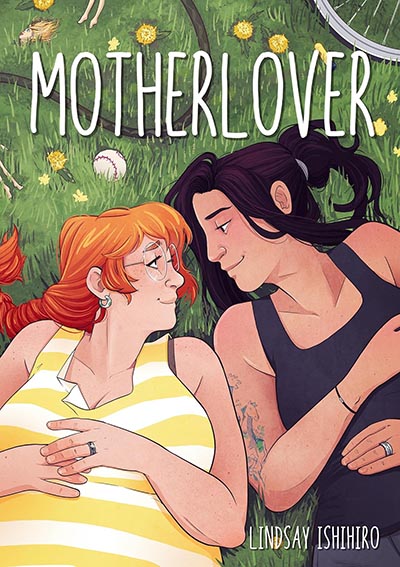

The two lead characters in Motherlover have both already got kids. Queer romance, says the blurb, “tends to favor young love and coming out stories”, but Motherlover “begins where most romance stories end”. It’s a “thrilling slow burn romance” about ‘second chances later in life’ which “centers motherhood and family”.

It runs to eighteen chapters and nearly 300 pages, but you can read it in a couple of hours, and indeed once you’ve started that’s what you’ll probably do. The chapters are short, the pace is brisk, the plot’s very well-organised and propulsive, and it never gets stodgy.

In the school playground, dumpy but cute Imogen, mother of four, meets her cool new neighbour, celebrity cellist Alex, a self-professed lesbian who is bringing up one daughter by herself. They soon strike up an unlikely friendship.

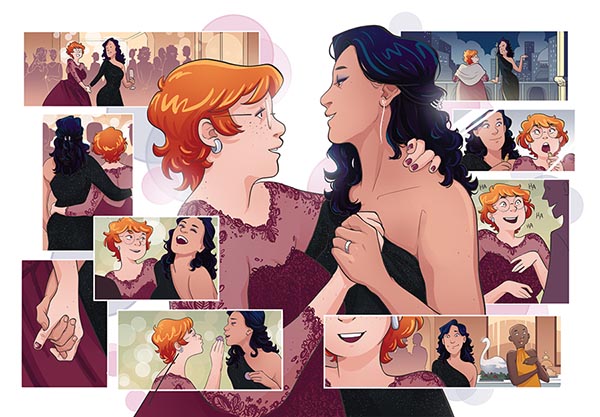

Imogen’s husband is a car-loving skater-boy bozo, telegraphed as a wrong’un from the outset. He’s mismanaging their money, he gets drunk and proposes a threesome with Alex, then he turns out to be having an affair. Imogen leaves with the kids, and takes refuge at Alex’s house. From that point onwards everybody keeps assuming that they’re a couple, until eventually Imogen realises that she’s fallen in love with Alex…

Overwhelmingly, the first impression is one of slick professionalism. Lindsay Ishihiro has worked on both comics and video games, and they built the two main houses in the story in The Sims, then used these to ‘stage reference photos’ for the backgrounds, which helps to explain why they look so convincing.

But despite the blurb’s claims about the originality of the story, there’s nothing here that will rock your world. There’s a strong aspirational theme – no sooner does Alex befriend Imogen than she starts urging her to go back to college, a move which her husband immediately attempts to nix: “College is really expensive, babe”. Leaving the lesbian angle aside, this theme – emotionally distant husband feels threatened by the idea of his wife making a new start – has been amply covered before, in things like Educating Rita and Shirley Valentine.

The slow-burn gentleness of the lesbian romance, the unapologetic plumpness of one of the main characters, and the focus on family life are all welcome. On the other hand there are aspects of the story which don’t bear much close inspection. Alex is meant to be a concert-standard cellist, but we only see her practising once, and there’s no hint of her needing to practise at all after Imogen and her family move in. Similarly, Imogen’s three youngest kids and Alex’s daughter are all unbelievably well behaved while their home lives are being upended and rebuilt.

Imogen’s oldest kid, Lucas (or ‘Lulu’), no sooner finds herself in the new household than she accidentally outs herself as a trans female, by trying on Alex’s high heels. This gives Alex a chance to have a bonding chat with her on the back porch, which is meant to give us a snapshot of how the two families are going to get along. But all the details of Lulu having to change from male to female at school, explain things to her friends, decide whether or not to have surgery and hormone treatment, and so on and so forth, are swept under the carpet.

The one place where the narrative does show a bit of depth is in the relationship between Alex and her brother Eiji. Their parents were conservative and controlling, and strenuously disapproved of Alex’s lesbianism. Eiji moved out, into a gay relationship of his own, but never came out to his parents and left Alex to take care of them until they died. Then he wrote a book about self-realisation.

We see Alex and Eiji meeting up on New Year’s Day and climbing a mountain to scatter their parents’ ashes. Alex is resentful towards Eiji, and he keeps harping on about his book. Some of his insights into Alex’s personality and situation seem shrewd, but they come with a strong whiff of self-serving pretentiousness. Both Alex and Eiji are ambiguous characters at this point, displaying a mixture of good and bad motivation, selfishness and unselfishness – and all of a sudden we get a real sense of human complexity and the difficulty of relationships, which is missing from the rest of the story.

All that having been said, this is an ultra-competent and ultra-commercial comic book. The draughtsmanship is superb throughout, and it’s never dull. It describes itself as a queer romance, and it certainly delivers in those terms. Think of it as a high-quality lesbian Mills and Boon, and you won’t go far wrong.

Lindsay Ishihiro (W/A) • Iron Circus Comics

Review by Edward Picot