In 2013, Palestinian cartoonist Mohammad Sabaaneh was detained while crossing the King Hussain checkpoint between Jordan and the occupied West Bank. This wasn’t altogether unexpected, as Sabaaneh has been working as a political cartoonist, artist and activist for some time, exploring the Israel-Palestine conflict from a Palestinian perspective. This time, however, he was arrested – without charge – and sent to an Israeli prison for five months, where he endured the privation of solitary confinement, overcrowded cells and brutal interrogations.

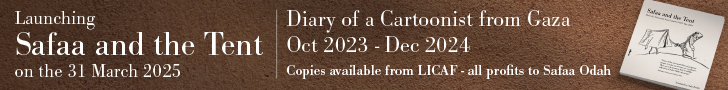

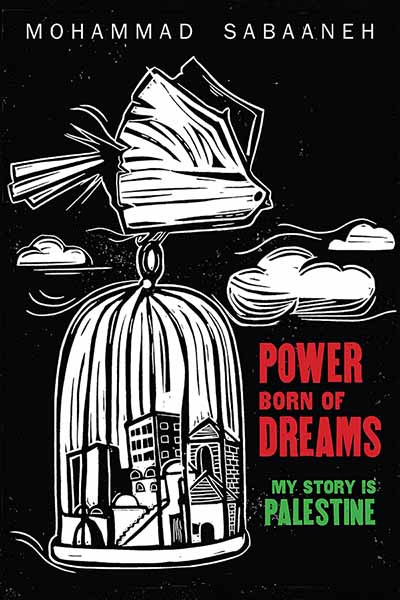

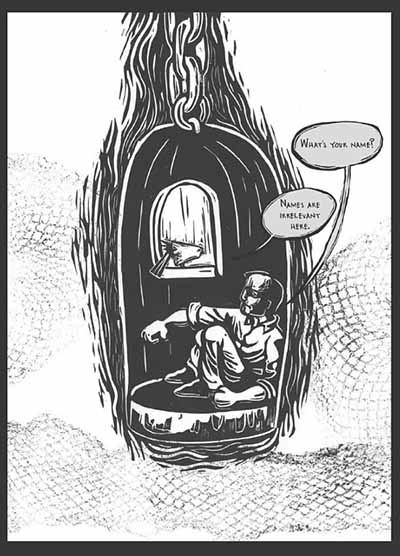

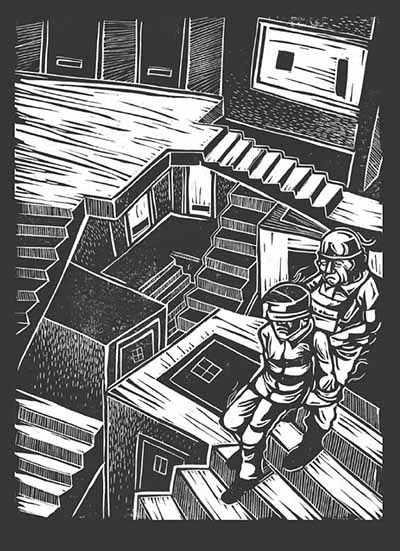

Power Born of Dreams: My Story is Palestine is Sabaaneh’s retelling of this story. It begins with those first disorientating months, giving us insight into his thoughts and emotions as he began the process of imprisonment, from his trial to his movement to various forms of confinement. The daily life of prison is a mixture of fear, sadness and inertia, and while Sabaaneh must deal with the sadness of separation from loved ones and the fear of each impending interrogation, he must also learn to pass the time, for example by playing kick-ups with a rolled up towel in his cell. It’s clear from the start, however, that this is not a straightforward journalistic account: each panel has been linoprinted and Sabaaneh exploits this medium to create an expressive and poetic retelling, with monstrous, gaping-mouthed guards and a prison landscape that twists and repeats like an Escher drawing.

The book moves away from its focus on Sabaaneh’s experience after he is visited by a bird who brings him stories of the lives of people from Jerusalem, the West Bank and across the surrounding territories. These stories form the core of the book. We learn of the constant drone of military aeroplanes tormenting the people of Gaza; the mother who must send her son to school across a warzone, knowing each day he may not return; the imprisoned father whose daughter does not recognise him upon release.

These stories were in fact taken from Sabaaneh’s conversations with other prisoners and they are given gravity through introductory texts and end papers that give historical and statistical information about the conflict. But although this is clearly a book about real things and real lives at stake, it is distinguished and animated by its magic realist elements and expressive art work, all rendered in thick, twisting white lines and black ink.

The choice of linoprinting has a symbolic as well as formal function: in the introduction, Sabaaneh’s explains how he attempted to etch his name on to the prison walls, as other prisoners had done, but found this too difficult. The post-hoc inscription of lino therefore serves as a gesture of solidarity with these prisoners, and it creates certain conditions for the storytelling. Linoprinting is after all not a medium that lends itself to deliberate subtlety. It is a tough process, forcing the artist to commit to strong, decisive gestures. The subtleties are in the mistakes and unforced errors – the bleeding of ink, the variation in the registration. It also works through the stark contrast of black and white. Sabaaneh has stated elsewhere that black is the colour that best describes life in prison in Palestine, and so the linoprinting process seems suited: the pages are filled with a thick darkness that bleeds out beyond the prison walls to consume the surrounding territories, the roads, the schools and the homes. But the landscape and its people remain persistent and quietly defiant with each print, in stubbornly unconquerable patches of light.

Some of the greatest art works in human history have explored the struggle to retain sanity, dignity and humanity while imprisoned and subject to degrading, inhumane conditions. We know of Victor Frankl and the concentration camps, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag Archipelago, the strength they drew from a resolve to eventually tell the world about their experiences and the conditions of their imprisonment. Sabaaneh now works within this admirable and desperately sad tradition. He used drawing during his imprisonment to record his thoughts and the stories of other prisoners on stolen scraps of paper, which he concealed as he was moved from cell to cell. In these circumstances, personal expression and artistic creation become acts of defiance and willpower, and they represent the ultimate triumph of the human spirit. The expressive quality of Sabaaneh’s linoprints seems to foreground this human element.

Power Born of Dreams is an affecting account of the human consequence of the Israel-Palestine conflict from a Palestinian perspective, and a useful text for those wishing to understand more.

Mohammad Sabaaneh (W/A), Dalia and Mouin Rabbani (T) • Street Noise Books, $15.99

Power Born of Dreams won the Palestine Book Award 2022 for best translated book

Review by Jon Aye