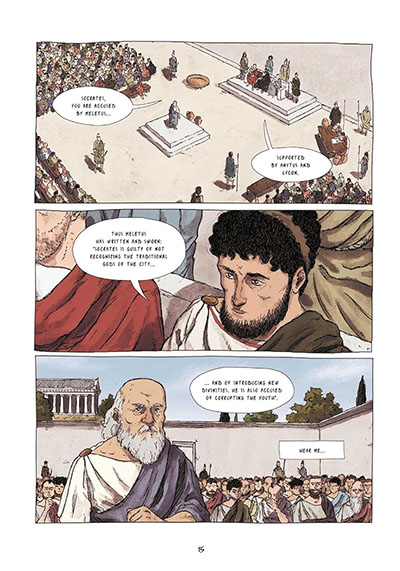

Socrates is essentially a courtroom drama. It deals with the trial of the Greek philosopher Socrates, known as the father of philosophy. As many readers will know, he was accused of impiety and corrupting the youth of Athens in 399 BC. After a trial lasting a day, he was condemned to death, accepted the verdict, and took his own life by drinking hemlock.

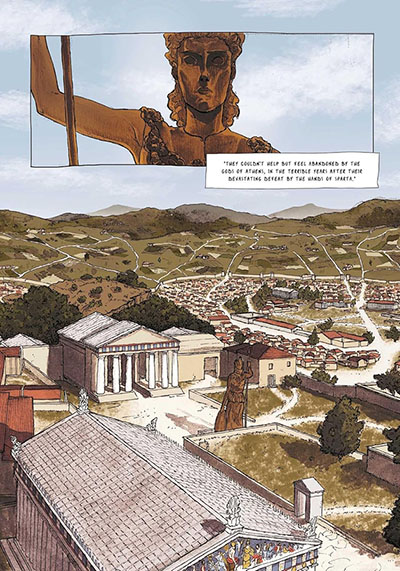

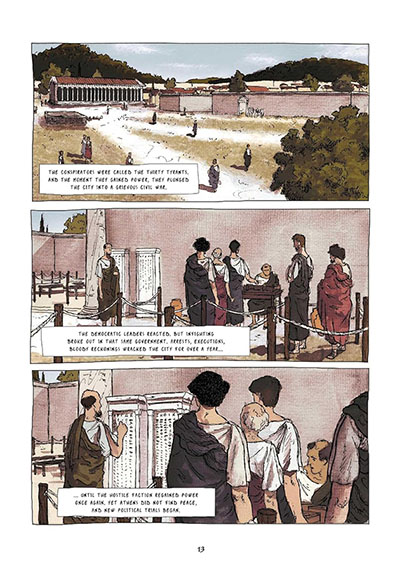

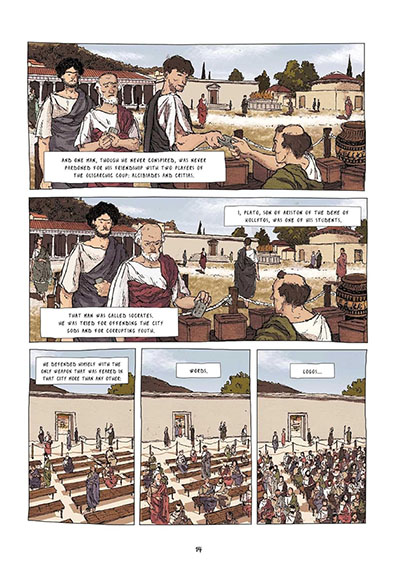

This was in a time of political turmoil, when Athens had been defeated by Sparta, and their democratic government had been overthrown and replaced by an oligarchy of tyrants, who were then overthrown themselves and replaced by the democrats again. Socrates apparently supported neither one side or the other, but criticised both, although he was friendly with some of the defeated oligarchs. He was perceived as a troublemaker, someone who kept asking awkward questions and undermining the authorities, and his trial was probably politically motivated.

The problem with courtroom dramas is that they are essentially static. The action is confined to a single place, and it consists of one person after another holding forth or cross-questioning witnesses, trying to persuade us of the rights and wrongs of a particular case. For the graphic novelist, as for the film-maker, the problem is how to open out the action, how to give us more than just a long sequence of head-and-shoulder shots with lengthy speech balloons attached.

Socrates uses a number of tactics to accomplish this. First of all, it doesn’t just show us the trial: it also shows us Socrates talking to his followers beforehand, about the likelihood that he might be arrested, and then afterwards in his prison-cell, when he says goodbye and calmly takes the fatal draught of hemlock.

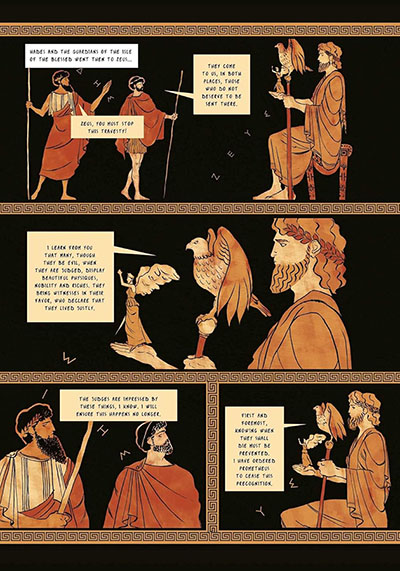

Secondly, it uses separate sequences to illustrate some of the arguments from the trial. Several of these are based on stories from Greek mythology – for example, there’s a section about the exploits of Heracles – and these are illustrated in the style of ancient Greek pottery, with reddish figures on a black background, and bands of geometric patterning.

Socrates’s method of pursuing an argument is often based on storytelling just as much as his more famous “Socratic questions”. He tells how the Delphic oracle once proclaimed him to be the wisest man in the world. The oracle could not speak falsely, says Socrates, but all the same “I am conscious that I am not wise, either much or little”. He therefore goes to various people who are reputed to be wise – politicians, authors of tragedies, and artisans – to find out more about their wisdom, and comes away from each of these encounters realising that actually they don’t know anything much. In the end he concludes that the others imagine themselves to be wise, whereas he is acutely aware of his own ignorance, and that’s the only respect in which he’s wiser than they.

Another important sequence is to do with the nature of love, and again this is illustrated in a different way from the courtroom scenes. Love is portrayed as a daemon, halfway between a god and a human, a troll-like figure with a flaming hole in the middle of his chest. This is not love in the sense of sexual desire or romantic attachment, but something which encompasses both of those and goes beyond them. “Love is the desire to possess what is fair, what is good”, argues Socrates, “and therefore… to achieve goodness, man shall not easily find one better to help him than love”.

Socrates’s method of dealing with the accusations against him, as these examples show, is not to rebut them directly, but to outflank them by drawing attention to the beliefs and principles which have motivated him in his way of life. This may mean that his lines of thought, and their relevance to the trial, seem tangential and a bit difficult to follow at times, especially for those without any prior knowledge of Socratic philosophy.

It should also be said that the Socrates we are given here has been slightly sanitised for public consumption. Wikipedia tells us that “He was notoriously ugly, having a flat turned-up nose, bulging eyes and a large belly”, and also that “He neglected personal hygiene, bathed rarely, walked barefoot, and owned only one ragged coat.” Socrates as drawn by Alessandro Ranghiasci, however, is an imposing elderly man with a white beard, rather like Moses, with occasional touches of Father Christmas.

One thing that does come across is his disrespectful sense of humour. When asked to give his opinion on what his own sentence should be, he suggests that the court should either pension him off in a nice property, as a reward for the service he has rendered to the state, or else impose a miniscule fine (“a mina of silver”), because that’s all he can afford.

The sense of humour makes him seem unexpectedly down-to-earth. But for Socrates, philosophy was not an academic “ivory tower” subject. It was an urgent attempt, in turbulent and bloody times, to distil a set of principles by which the citizens of Athens could live and govern themselves. He was not a detached hermit, but a deeply political figure, either a troublemaker or the scourge of hypocrisy, depending on your point of view. He paid for his outspokenness with his life, and the achievement of this book is not only that it brings him to life as an individual, but that it shows his thinking at work in the life-and-death context of his times and his trial.

Francesco Barilli (W), Alessandro Ranghiasci (A), Giulia Gabrielli (L) • Mad Cave Studios, £17.99

Review by Edward Picot