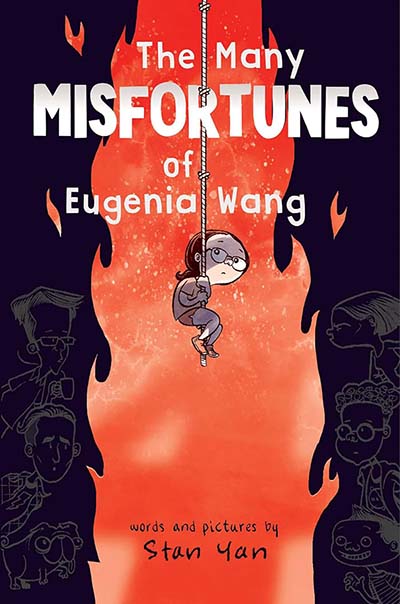

The Many Misfortunes of Eugenia Wang sets off as if it’s going to be a graphic-novel version of Diary of a Wimpy Kid, with an Asian slant. But it soon heads into supernatural territory.

Eugenia, the title-character, wants to be a comic-book artist. At the beginning of the story she picks up a flyer for a comic art summer camp, and decides to apply for a place. But her mother rejects the idea out of hand: “You already waste too much time on cartoon. Art not helping you be a doctor or lawyer.”

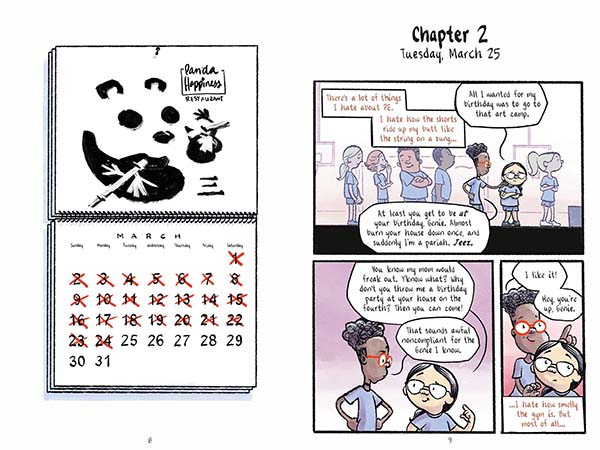

Eugenia is a few days away from her thirteenth birthday: but her birthday falls on the fourth of April, and four is an unlucky number in Cantonese (the word four and the word death are both pronounced “sei”), so her mum insists that her birthday party should be held on the fifth. Eugenia decides to have a party on the fourth at the house of her best friend, Keisha, and to apply for the comic art summer camp in secret.

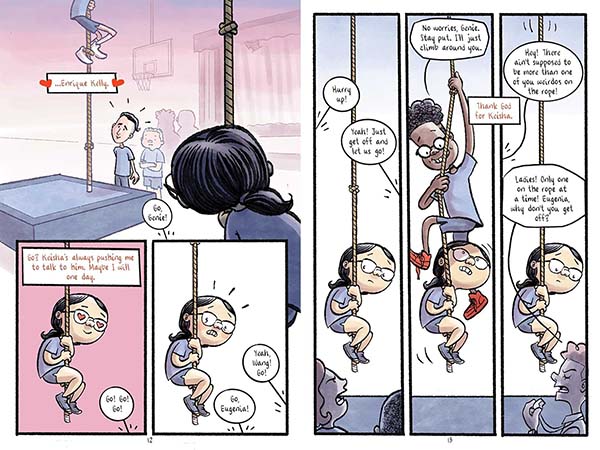

Then something odd happens in gym class at school. Keisha falls off the top of the climbing-rope and clonks Eugenia on the side of the head with the heel of her trainer. Eugenia has a concussion-vision – herself at home, in the middle of the night, clutching her secret application for the art camp and trying to escape from a house-fire which has just broken out.

When she comes round from her concussion, she draws the dream as a comic-strip (“It was so weird, I needed to draw it before I forgot it”). But the dream keeps coming back, and every time it comes back, a new element has been added to it – Keisha falling out of the window, her dad trying to put the fire out, Enrique (a boy from school she has a crush on) trying to help, her little brother William getting dragged into the disaster too… Every time she wakes up, she finds that she has unconsciously drawn these new elements into her comic-strip. Is she having visions of the future, or is the spirit-world trying to send her warnings, either through her dreams or her drawings or both?

The book is about 130 pages long, and divided into chapters, each chapter representing another day ticked off the calendar towards Eugenia’s birthday. Most of the pages are dominated by shades of blue, but the house-fire dream sequences are in dramatic red and black. The drawings are always crisp, the layouts extremely well-composed, and the characters sharply differentiated from each other. At the end of the book, in an afterword, Stan adds a couple of pages devoted to ‘My Process’, which show us how he starts from a script and works through rough layouts to the finished pages, and also how he designs his characters.

A couple of those characters feel under-developed, however. Eugenia’s Dad and her school crush, Enrique, never really come to life. Oddly enough Eugenia’s maternal grandmother, Po-Po, feels like more of a genuine presence in the story, even though she’s dead and never appears in person. But this oddity points to the central theme of the book, which is the inter-generational tension in Chinese-American families. Po-Po was a first-generation immigrant, and had to subordinate everything else to the need to “make good” and find some financial security in her new country. Eugenia’s Mum is following the same tradition: she demands that Eugenia should get straight As at school and find her way into a well-paid career (“Art not helping you be a doctor or lawyer”).

Eugenia herself, born and brought up in the USA, wants to be allowed to do her own thing. Clearly this is autobiographical territory for Stan Wang, who in his Afterword thanks his Dad “for coming out to support me in an endeavor that was so far removed from the finance career he likely wished I was still in”.

The tension between Eugenia and her Mum – or between the individuality of third-generation Chinese-Americans, and the strict conformity demanded by their forebears – is what seems to lie behind the house-fire dream-sequences. Is her determination to become a comic book artist somehow bringing ruin and disaster not only onto herself but her home and family? This underlying theme is at the core of the book, and gives it an extra dimension which makes it more than just a comedy-horror for kids.

Stan Yan (W/A) • Atheneum, £8.99

Review by Edward Picot