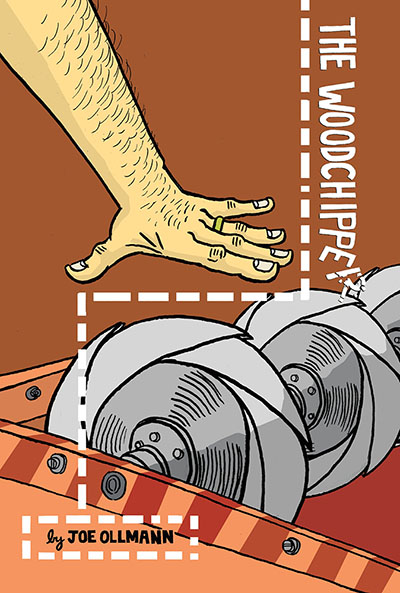

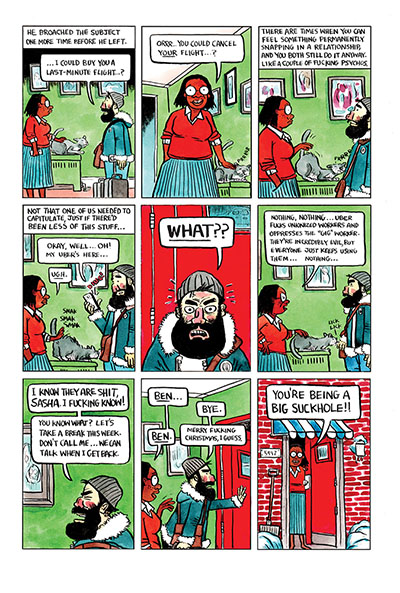

An interesting assessment of Joe Ollmann’s work appears early on in his own introduction to this latest collection. It comes from the late American critic Tom Spurgeon who once reportedly described the endings of Ollmann’s stories thus: “There’s a lovely thought that seems to connect a few of the stories where the protagonists kind of let themselves off the hook a bit, providing their own moments of grace.” It is, as the cartoonist points out, a wise opinion, and one that is more than justified when one reads The Woodchipper.

Ollmann’s introduction also serves as a reminder, before getting to the actual stories themselves, that this is an artist completely at ease with his medium, and aware of why he chooses to do what he does. It is a heartening thing when one acknowledges how economic realities are compelling so many other creators to make compromises at every turn. The introduction ends with a declaration of how ‘attempting to calculate something “marketable” only makes for shit art,’ and what follows is testament to how seriously Ollmann adopts that rule for himself.

For those familiar with his work, this is an unmissable addition. The five stories do what the best short fiction aspires to in prose, something Ollmann effortlessly pulls off through his panels. For those considering reading him for the first time, this is as great a place to dip your toes into as any.

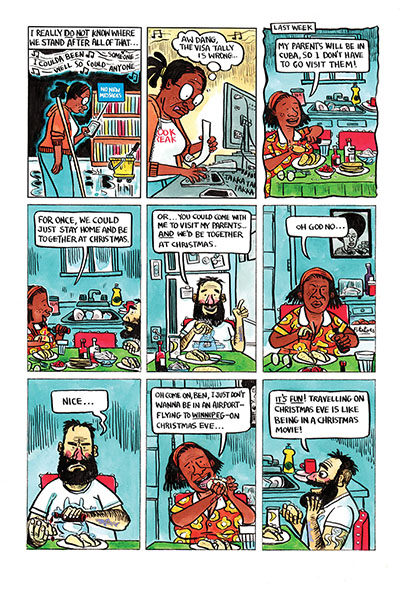

A couple of years ago, while promoting his book Fictional Father, Ollmann told Broken Frontier how he believed that “people who really get things, have been through the shit in some way…like they operate at a different level of compassion and understanding due to their experience.” The characters who appear in The Woodchipper all share that sense of empathy drawn from some everyday experience that invariably leaves a deep impact on their individual psyches. The title story, for instance, is a masterclass in how a seemingly innocuous incident can have life-altering consequences. Nothing awful appears to happen, and yet, the anxieties faced by Ollmann’s troubled protagonist seem all too plausible. It is amusing and unsettling in equal measure.

The second tale is like one of those yarns that makes for great conversation at any party — a ‘what if’ scenario that is as entertaining as it is frightening because of how engaging Ollmann’s style is. It’s the sort of story one can’t help staying with because of how easily it sinks its hooks into the reader. At the heart of the book is a story that is almost like a novella, about a security guard working at a place where what passes for scientific advancement blurs the lines between good and evil. It is particularly unnerving because of the times we live in, where so much that is advertised as beneficial ends up being a front for a capitalist system of exploitation. This is also a story good enough to stand on its own, which makes the remaining two seem almost like a bonus.

Alice Munro — another Canadian famous for her short stories, among other things — once described her chosen form as not like a road to be followed but more like a house, where one stays for a while, wandering back and forth, discovering how everything relates to each other and how the world outside is slowly altered. Ollmann’s work appears to take a similar approach, where it is less the point of a story than the subtle alteration in how a reader moves through it that matters. One can read The Woodchipper, put it aside, then read it again to discover something new. It is undeniably interesting, very readable, and highly recommended.

Joe Ollman (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly

Review by Lindsay Pereira