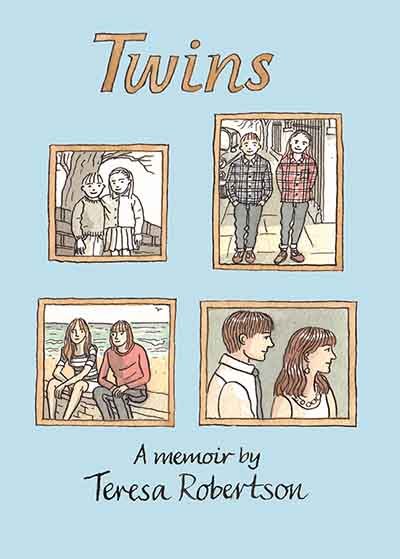

It’s mentioned on the back cover of the book, so it isn’t giving anything away to say that Twins is largely the story of Teresa Robertson and her twin brother Adam, who was tragically killed in a motorbike accident at the age of 28, just as Teresa was about to give birth to her first baby.

There’s much more to it than that, though. It starts with a black and white section, telling the story of how Teresa and Adam’s parents, Rosemary and Patrick, first met and fell in love while they were working together as theatre designers in the 1950s.

This theatrical background plays a big part in how the twins’ lives unfold. Neither of them is brilliant academically, but they’re both creative, and they’re brought up in an atmosphere where a career in the arts is seen as a valid option rather than a waste of good education or a one-way ticket to penury.

It helps that their grandmother is rich, although her largesse has to be spread out between 15 grandchildren. In 1987, for example, Teresa says to her Dad “Is there any of Granny’s money left?” – and when he says yes, she uses it to buy herself a house-boat.

On the other hand, while the grandmother’s money pays for 11 of the 15 grandchildren to go to boarding school, Teresa and Adam go to state school – from a mixture of “Cost, principles, naivete and bravery”, as Teresa puts it. Their parents get a job with the Nottingham Playhouse, so the family moves from Highbury to Nottingham, and Teresa and Adam both end up at a Nottingham secondary school, where they stick out like sore thumbs because of their middle-class background and southern accent.

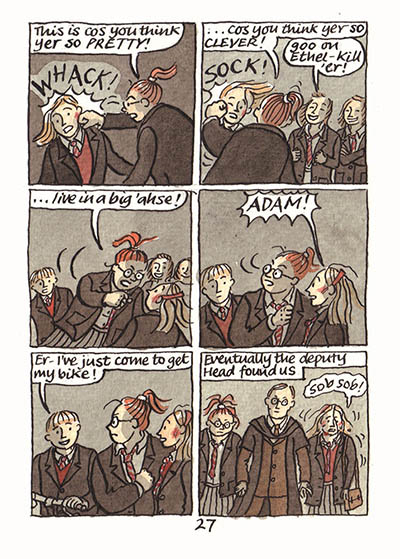

Adam is victimised by a boy called Peter, who we see chalking up “Adam is Queen of the Poofs” on the class blackboard. Teresa gets bashed up by a girl called Ethel – “This is cos you think yer so pretty! Whack! …Cos you think yer so clever! Sock!… Live in a big ‘ahse!” But the next morning, when she turns up covered in bruises, “All Ethel said was ‘O right me old prune?’ – and never hit me again”.

As these incidents show, there’s a vein of social commentary running through the book, but the tone is always deft and humorous rather than declamatory.

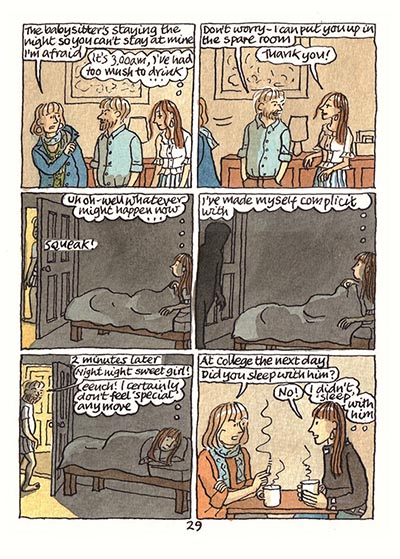

There is a vivid depiction of student/young adult life in the 1970s. We see Teresa and Adam working their way through a series of squats and rentals, and Teresa getting entangled with a series of unsatisfactory men. One of the most memorable is a creepy bearded tutor (“He’s so wise and mature compared to the boys my own age!”) who gets her drunk and then persuades her to spend the night in his spare room, so he can try his luck in the middle of the night (“Uh-oh – well whatever might happen now, I’ve made myself complicit”). Again the tone is light and humorous, but there’s also some acute observation here, not only of the sexist exploitation Teresa encounters, but of her own willingness to delude herself in her search for love.

Eventually, she finds her way to John, a 41-year-old poet with two teenage kids – “a worthy winner of The Husband Quest”, as she puts it in her afterword to the book. She gets into a permanent relationship with him, and becomes pregnant. But it’s during the pregnancy that Adam is killed, on a motorcycling holiday in France.

Another thread which runs through the book is fatalism, tinged with belief in the supernatural. At college, Teresa takes an extra-curricular module in parapsychology, and gathers that she may have empathic or telepathic powers. She then writes a story, in which her Grandpa forsees Adam’s death in a bike accident. Shortly afterwards, at a party, a girl is giving palm-readings, and accurately tells Teresa that she’s more obsessed with home than ambition – but then takes one look at Adam’s palm and decides to go and get a drink, rather than tell him what she sees there.

Robertson herself is strangely calm and accepting about Adam’s motorbike accident, and much of the latter part of the memoir is given over to events which seem to make sense of his death by showing it as part of a larger pattern. She learns that both her mother and Adam’s girlfriend have had visions of him since he died – the girlfriend had hers (“I went so close I could see the stubble on his chin”) just as the letter announcing his accident was being delivered. Teresa and John inherit the value of Adam’s flat, and use it to buy a house of their own. Then many years later, in 2016, Teresa realises that her life falls neatly into two halves – “28 years a twin, 28 years a mother”. And “at almost exactly the age I’d been when I’d lost Adam”, her first child Callum has children of his own – twins.

It’s a very feminine book. It’s beautifully drawn, in a style reminiscent of both Posy Simmonds and Raymond Briggs. It’s about families and friendships, and the ways in which life plays out through them. It contains so many friends and relations that it can be a bit difficult to keep track of them at times, but its complexity in this regard feels like the complexity of real life. It’s about babies growing up and becoming parents themselves, and then the pattern repeating itself. It deals with old age and death – we see both of Robertson’s parents getting old and dying – but it finishes on a note of renewal and optimism. Highly recommended.

Teresa Robertson (W/A) • Self-published, £18.00

Review by Edward Picot