There are some people who are as familiar with the life and work of Eadweard Muybridge as most of us are with what Hollywood stars seem to be working on. For these folk in the know, the latter’s work pales in comparison with the former, given his outsized influence on cinema and the art of moviemaking. Guy Delisle was introduced to Muybridge as a student of animation, apparently, and must have liked what he studied enough to revisit the man’s story decades later.

To be fair, it is an undeniably interesting story, with twists, turns, and ravages of fortune, all depicted with the deceptive simplicity that informs everything Delisle turns his questioning eye to. He has long had a knack of taking complicated subjects and effortlessly making them easier to comprehend, but this is possibly the first time he has applied that technique to biography.

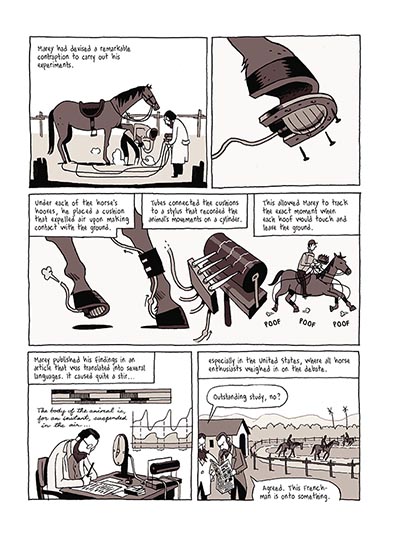

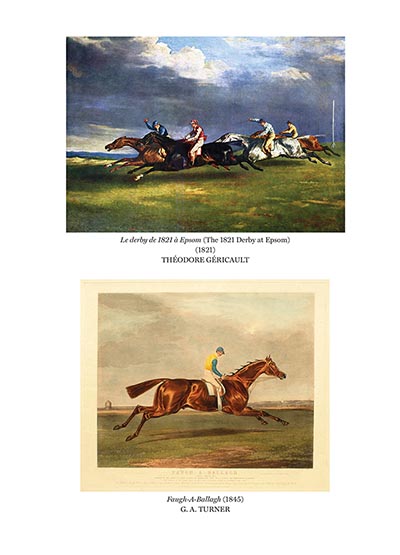

At the heart of the book is what drove Muybridge to try and answer a question posed by many artists of the 19th century: how do horses gallop? There were theories, as well as numerous embarrassing attempts by painters, but none could figure out if all the hooves left the ground simultaneously until the Englishman living in America decided to try and figure it out. What he ended up doing helped usher in an era of filmmaking that we take for granted today.

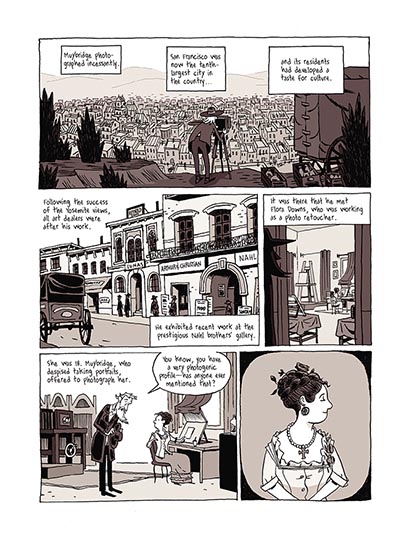

The story is told chronologically, but only from the point where Muybridge departs from England to make his fortune in the New World. It documents his initial failures, illnesses, short married life, and repeated attempts at finding a purpose until he stumbles upon photography. Delisle also brings a certain poignancy to Muybridge’s personal life, which was tragic. What lifts this otherwise linear narrative is the inclusion of the earliest attempts at photography — from the first photograph ever taken (by Nicéphore Niépce in 1827), to the first daguerreotype captured by Louis Daguerre in 1838, along with other efforts that throw everything that came after into sharp relief. Some of the work that made Muybridge famous — his photographs of Yosemite, Alaska, even the homes of billionaires — are featured too, allowing readers to appreciate the enormity of what these pioneers accomplished.

It’s interesting to try and imagine what drives Delisle to his subjects. Why does he look at World Record Holders, for instance, or turn back to his youth for Factory Summers? At times, one imagines it is the need to take on the role of impartial observer, as he has executed to perfection over years of travelogues. At other times though, it’s almost as if he uses his personal history to shine a light on some universal condition. What comes through consistently, irrespective of what he eventually alights upon, is a sense of empathy that makes his stories so compelling.

Ultimately, after turning the last page, one must ask oneself if Eadweard Muybridge was a genius or just a crazy Englishman. The answer lies somewhere in between, because of the flaws and complications that define the lives of every public figure. It’s also why this isn’t just a book for fans of Guy Delisle. It is for anyone who has stared at a photograph a little too long or watched a movie in awe.

A powerful reminder of how technology can be treated as an aid if approached in the right spirit, it is also a topic more relevant than ever in our time of Artificial Intelligence, when artistes are being threatened with extinction all over again, the way painters once were.

Guy Delisle (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira