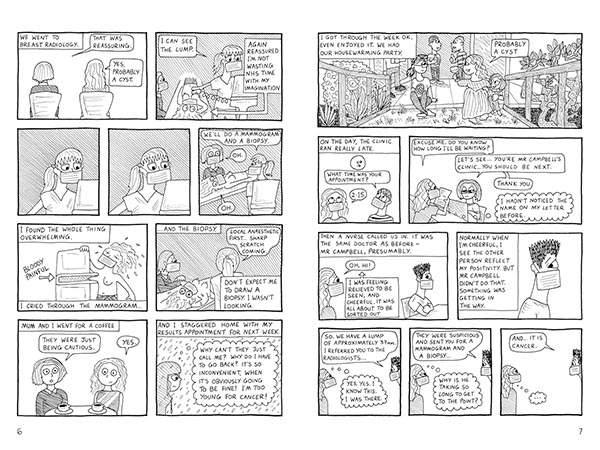

“One night in April 2022”, begins Hayley Gullen’s memoir, “PAIN PAIN PAIN. [thought bubble:] That’s weird… Wrong time of the month and only one boob. Oh. It’s stopped. [Yawn] I’ll check it in the morning.”

The pictures show Hayley and her partner Dan lying blissfully asleep with little smiles on their faces; then “PAIN PAIN PAIN” radiating from Hayley’s side of the bed, surrounded by lightning-strikes, and her eyes popping open in alarm; then, when the pain stops, the two of them lying blissfully asleep, smiling again.

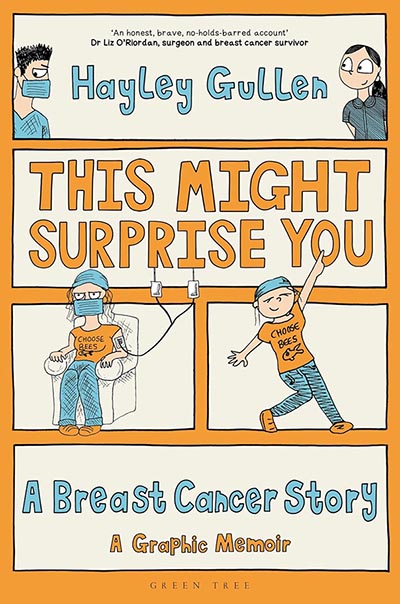

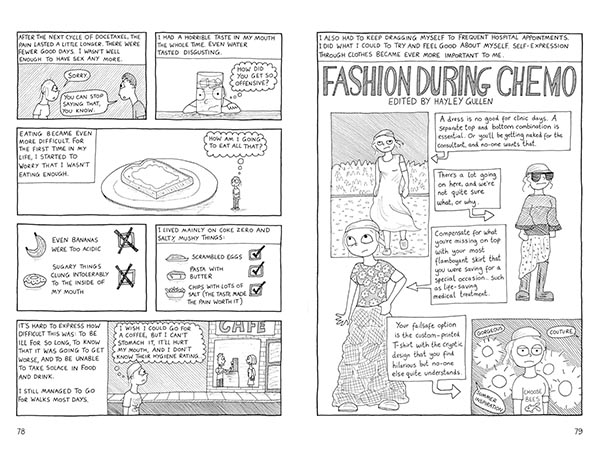

The tone of the whole book is established in that first page: the simple, ideogram-style drawings which dramatise what’s going on; the exaggerated facial expressions which tell us how the characters are reacting; the frankness and specificness of the language (“Wrong time of the month and only one boob”); and the humorous approach, which engages us immediately and carries us through the whole story.

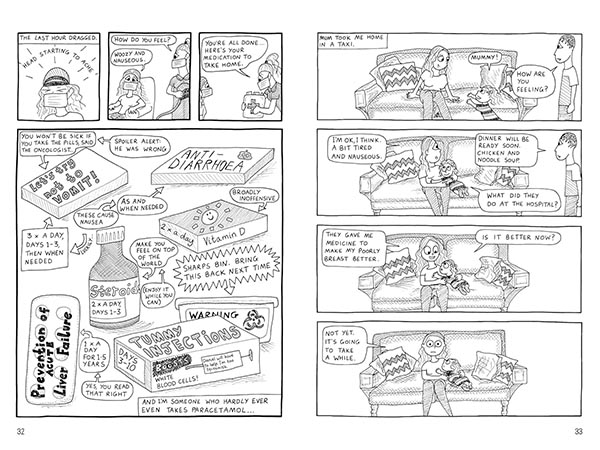

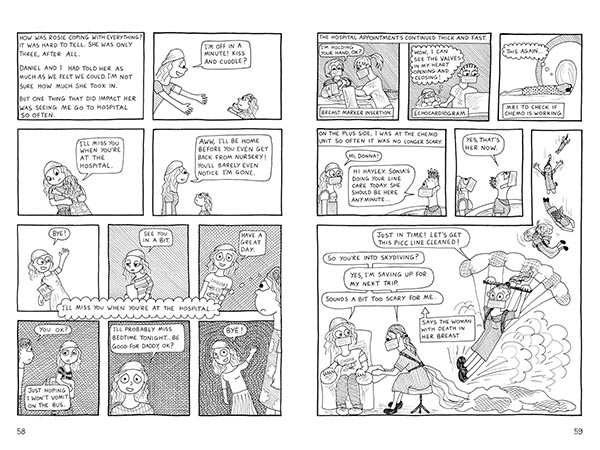

This is a book about one woman’s experience of breast cancer, but you don’t need any personal experience of cancer to get something from it. It goes into detail about breast cancer treatment: the scans, the drugs, the blood tests; chemotherapy, radiotherapy and their side-effects; exhaustion, hair-loss, toenail-loss, mouth-ulcers, loss of appetite, etc. etc. But on top of this it’s got lots of wise things to say about coping with traumatic life-changes, and lots of insight into the workings of the NHS.

“I’ve heard becoming a parent being likened to falling through a trap door,” comments Gullen. “Once you’re in, there’s no going back”. Cancer, she says, is another trap door. To illustrate this she divides a page into horizontal panels linked by trap doors. The women in the top panel are young, smiling, having fun; in the middle (through the parenthood trapdoor) they’re heavily pregnant but still smiling; in the bottom (through the cancer trapdoor) they’re bald, intubated, and they look chastened. The different layers represent different stages of adulthood, but also deepening degrees of grimness, an abbreviated journey from innocence to experience. “But I chose parenthood”, remarks Hayley ruefully. “I didn’t choose this.”

It’s a page which demonstrates how inventive she can be in her layouts, but also how she uses this inventiveness to convey complex ideas. The humour is ever-present; the drawings are always sprightly and quirky; but there’s some serious stuff going on here at the same time.

She’s disarmingly frank throughout the book. Probably the best example of this is her discussion of sex during chemotherapy. She fancies a bit of “light BDSM” – being tied up during sex – but she’s worried about cutting off the circulation to her hands. A sex podcaster suggests trying a straitjacket, but she doesn’t like the idea. In the end she buys herself a pair of custom-made leather cuffs: “Best £50 I ever spent.”

She also shows us what it’s like to be on the receiving end of NHS treatment. She’s clearly grateful for the care she received, and she developed close personal relationships with several of the clinicians, but at the same time she’s always conscious of a pressure to make the patient fit the system, rather than the system trying to accommodate the patient. This is a theme which recurs throughout the book.

Things come to a head when the main part of her treatment is complete, but she’s still receiving a comparatively innocuous type of chemotherapy (Kadcyla). Hayley gets an infection in her picc line, and ends up in A&E. Suddenly the structured first-name-terms environment of her “usual” treatment is gone, and she’s just another punter, bewildered and isolated, experiencing the chaotic nature of emergency care – long waits, different medics saying different things, attempts to fob you off with an appointment in several days’ time… In the end she feels obliged to make a complaint, which leads to soul-searching on both sides.

It’s a common experience of cancer patients that while they are undergoing treatment they feel oddly secure, because however punishing the experience may be, it’s also very structured and supportive. Often the patient’s coping mechanism is to shelve any attempt to deal with the emotional fallout of the diagnosis, and focus on just getting from one stage to the next: but then, when your treatment comes to an end, there can be a real sense of abandonment, plus a huge bundle of unresolved issues. Gullen deals with this aspect of her journey in some depth – she shows a cartoon version of Hokusai’s big wave hanging over her head, threatening to overwhelm her, but describes how she gradually manages to drain it away with the help of a psychologist.

She also processes her cancer experiences through her Quaker faith, and the belief Quakers have that anyone can speak up and give voice to the truth inside themselves – what they call “Ministry”. Throughout Gullen’s journey, she is acutely aware that the medical system has a tendency to reduce her to a diagnosis, whereas she wants to be a person. Being funny about her experiences, and translating them into little cartoon drawings, is one of the ways in which she attempts to assert her individuality, and eventually this leads to the birth of This May Surprise You. “This is my ministry,” she says right at the end of the book.

Does she mean creating comic books, or telling us about her cancer? I think she means both.

Hayley Gullen (W/A) Bloomsbury/Green Tree, £14.99

Review by Edward Picot