The typical conspiracy theory is anchored in the idea that invisible agents in our midst control the world around us. That all power structures and figures of authority are a façade erected to conceal the machinations of the true rulers of the world. Yet these all‐powerful rulers are still imperfect, and information revealing their presence slips through the cracks. The information is there if only we would look. This idea, that paying attention to subtle clues would reveal deeper truths about the larger narrative is not exclusive to the paranoid. In comics, using subtle details to signal to the attentive reader is a long-standing technique. Pete Toms in Dad’s Weekend not only tells us the story of a man consumed by his conspiracy theories, but also succeeds in using to medium to create a genuinely paranoid comic. Dad’s Weekend leaves the reader distinctly ill at ease through both the events of the story and the way in which it is rendered.

The typical conspiracy theory is anchored in the idea that invisible agents in our midst control the world around us. That all power structures and figures of authority are a façade erected to conceal the machinations of the true rulers of the world. Yet these all‐powerful rulers are still imperfect, and information revealing their presence slips through the cracks. The information is there if only we would look. This idea, that paying attention to subtle clues would reveal deeper truths about the larger narrative is not exclusive to the paranoid. In comics, using subtle details to signal to the attentive reader is a long-standing technique. Pete Toms in Dad’s Weekend not only tells us the story of a man consumed by his conspiracy theories, but also succeeds in using to medium to create a genuinely paranoid comic. Dad’s Weekend leaves the reader distinctly ill at ease through both the events of the story and the way in which it is rendered.

The plot of Dad’s Weekend follows our teenaged protagonist as she spends a chaotic weekend with her father. Whitney is smart and sarcastic, a modern day Enid Cole, and in all respects the sensible counterpoint to her unhinged father. Whitney’s father has become fully dedicated to his belief in reptilian body snatchers and coded messages hidden within “darkwave adult contemporary” music. Beliefs he has taken to YouTube to share with the world much to Whitney’s embarrassment. He will continue to embarrass her as he drags her deeper into his delusions regarding the disappearance of his friend Jim, leading to an assault on Jim’s widow, jail time, staring a fistfight with a priest at Jim’s funeral, and even further jail time. All actions her father believes are warranted by the signs and symbols of the lizard people’s presence he alone perceives. The question then is whether or not what he is seeing is real.

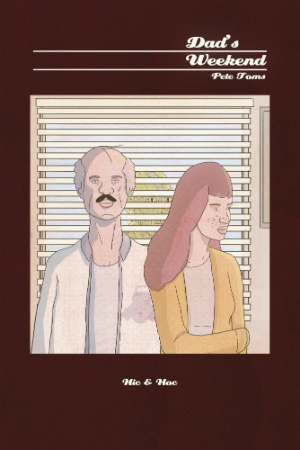

Toms’ artistic choices in Dad’s Weekend are where he starts to elevate this comic far beyond the story of a dysfunctional family. Even from the cover there are hints that all is not as it seems. A lizard man lurks behind venetian blinds that our main characters are standing in front of. The unobservant reader might miss his presence there, as they might also miss his more camouflaged appearance on the title page or the “They Live” style coded messages that pop up in the YouTube banner ads. If you start looking for lizard men, you will find them, as Whitney’s father does in the album covers of Byron Gravity.

Toms’ artistic choices in Dad’s Weekend are where he starts to elevate this comic far beyond the story of a dysfunctional family. Even from the cover there are hints that all is not as it seems. A lizard man lurks behind venetian blinds that our main characters are standing in front of. The unobservant reader might miss his presence there, as they might also miss his more camouflaged appearance on the title page or the “They Live” style coded messages that pop up in the YouTube banner ads. If you start looking for lizard men, you will find them, as Whitney’s father does in the album covers of Byron Gravity.

He will also find the coincidence he is looking for when Jim’s wife winks at him in exactly the same way Gravity did on Twitter in response to a question about who owns “the human genome copyright.” But we the readers see it as well. Just as we see the lizard skin beneath Jim’s funeral make up, and the lizard people milling about after the brawl in the church. That final panel is of particular interest because with her father in the back of a squad car, it is ambiguous whether it is Whitney seeing these lizard people, or just the reader.

However, the real boogeymen in Dad’s Weekend are not lizard people or out of control parents, but is rather our own existential dread. The delusions of Whitney’s father come from his compulsion to “find out why we were here.” The birth of his daughter caused him to question his existence and in finding no answers to his question he creates a fiction that serves as an answer. The tragedy is that even in his moment of clarity he cannot see this. He rails against Christianity insisting that no one his daughter’s age “would believe any of this shit!” But does The Ancient Order of the Poodle offer any better understanding of existence? This tragic search for meaning is mirrored in Jim’s wife who explains that after having spent years pushing “towards an inner, ultimate cosmic awareness,” she came to find “there’s nothing underneath.” Even the no-good teens we see at the beginning of the story are unable to find answers, only an acknowledgment of the charade of existence. One boy’s plan of being a “failed arthouse film director” is as much a fantasy as it is an admission of the cynical nature of grasping for fame. If we are doomed but know it, does that make it any easier to bear?

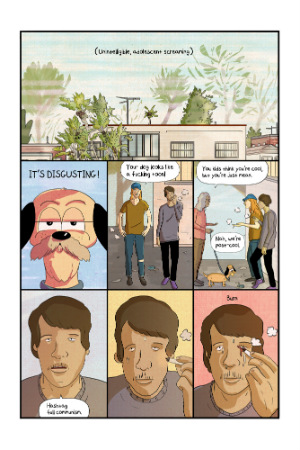

Toms’ ability to render the intricacies of his character’s performance only further accentuates the quiet desperation and despair they are going through. In close-up Whitney’s father is wild-eyed and sweaty, yet his forced smile reveals how much he wants to relate to his estranged daughter. That he carries himself in imitation of a tough guy when he is in the full swing of his delusions is equally telling. The two teens are dead-eyed and slack-bodied even as one puts a cigarette out under his eye.

Toms’ ability to render the intricacies of his character’s performance only further accentuates the quiet desperation and despair they are going through. In close-up Whitney’s father is wild-eyed and sweaty, yet his forced smile reveals how much he wants to relate to his estranged daughter. That he carries himself in imitation of a tough guy when he is in the full swing of his delusions is equally telling. The two teens are dead-eyed and slack-bodied even as one puts a cigarette out under his eye.

The weariness and composure in the face of adversity shine through in the way Toms renders Whitney’s reactions to the unfolding disaster around her. The use of muted, hazy pastels keep the ever-escalating narrative grounded in reality, though the move from the blue sky of morning to grey afternoon and latter purple dusk nicely hint at the emotional drain Whitney is spiraling down in regards to her father. While his own ridiculous bright white jacket (one of the few fully white surfaces in the comic other than word balloons) reminds the reader that he is still the pathetic clown seen showing off said jacket on YouTube on the first page of the comic.

While only 30 odd pages, Dad’s Weekend packs as much meaning and craft as most full-length graphic novels. Toms succeeds in taking the reader on as equally uncomfortable a journey as Whitney is on herself. It’s a work that acutely makes us question how we find meaning within our cosmically small and ludicrous existence. Even if the best it lets us do is make some good cryptic Facebook updates.

Pete Toms (W/A) • Hic & Hoc, $6.00

Review by Robin Enrico