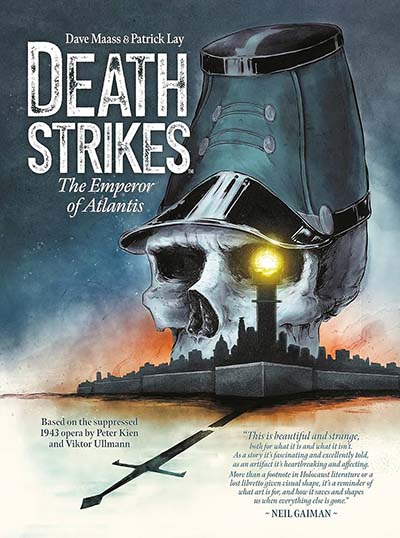

Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis is one of the most remarkable projects to come out of the Berger Books line at Dark Horse Comics to date. This graphic novel is based on an opera written in 1943 by Peter Kien and Viktor Ullmann, two prisoners at the Terezín concentration camp. Neither man would live to see a performance of their work.

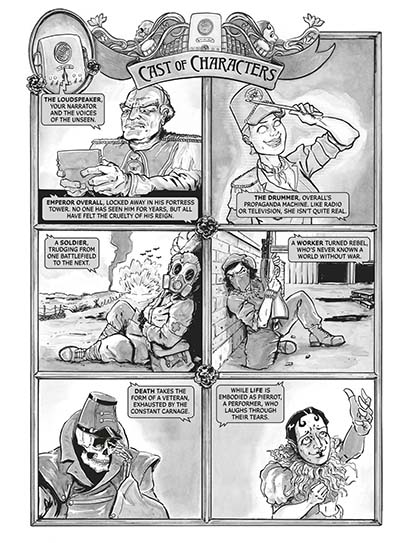

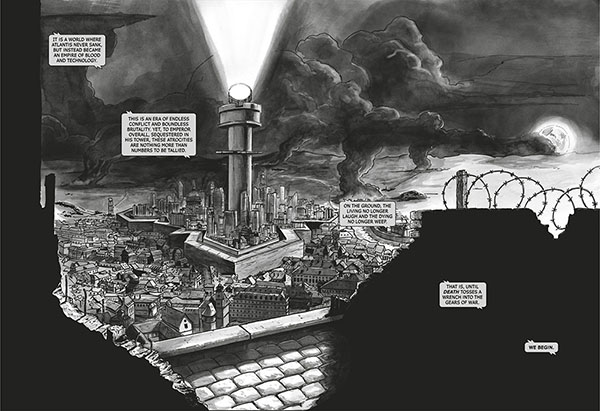

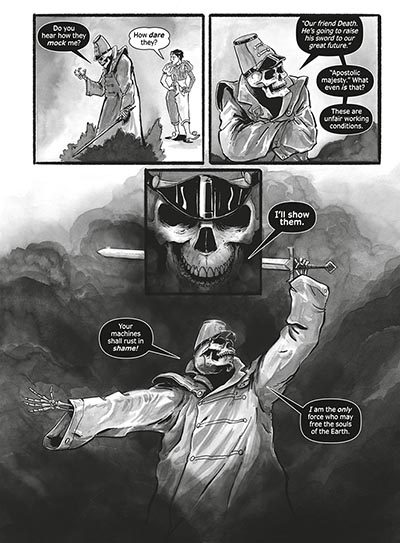

Adapted to the comics page by writer Dave Maass, artists Patrick Lay and Ezra Rose, letterer Richard Bruning and, of course, edited by Karen Berger, the opera’s message now finds a new audience in a different format. This story of a world where Atlantis rules, its insane ruler declares war on everything, and where Death goes on strike, feels as relevant in our current dystopian reality as it was when it was originally created.

I caught up with writer Dave Maass to talk about the intricacies of cross-media adaptation, the incredible array of extra contextual material in the book, and the timeless nature of the themes of Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis…

ANDY OLIVER: How did you first discover the story behind Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis?

DAVE MAASS: In the late 90s, I was your stereotypical mall punk, and one day when I was browsing through Best Buy in Paradise Valley, Arizona, I found a classical CD sampler and VHS documentary about music suppressed by the Nazis. I brought it home and listened to the whole thing. I was instantly captivated by an excerpt from Der Kaiser von Atlantis and had to find out everything I could (which wasn’t easy, since the internet was still pretty new). It kinda shaped my life, in terms of thinking about the role of expression in society and the power of art to resist oppression rather than just rebel against norms. The story isn’t that glamorous, but it goes to show that you can find inspiration just about anywhere.

AO: Can you give us some background on the opera’s creators Peter Kien and Viktor Ullmann?

MAASS: Peter Kien was in his early 20s and a whirlwind of creativity: he could write, he could draw and paint, he could even make puppets. Ullmann was in his 40s and a very serious avant garde composer and music critic. They shared a News Year birthday and a hardened commitment to their art. In a way, their collaboration is reflected in the dynamic of the characters of Life and Death–a young emotional upstart and a bitter, jaded veteran.

AO: Why did you feel the comics form, in particular, was a medium so well suited to capturing the themes of The Emperor of Atlantis and bringing them to new audiences?

MAASS: Operas are a very interesting medium, full of emotion and expression, but they’re not particularly accessible to popular audiences. While Der Kaiser von Atlantis is occasionally performed, unless you’re in a particular city on a particular night, you’re going to miss it. Even if you do see it, you might not fully understand it if you don’t speak German or have a background in classical music. By producing it as a graphic novel, we’re creating a record that can sit on anyone’s shelf and that you can revisit over and over again. Kien was both a literary and a visual artist, and so the story naturally lent itself to the medium, especially since it blends so many genres.

AO: One of the greatest challenges of translating work from one medium to another is in keeping the spirit of the original source intact while recognising the need to adapt certain elements to a new method of narrative delivery. With that in mind were there any amendments you needed to make to the story? How did you approach the adaptation in that regard?

MAASS: It was a challenge, as you say, but a really rewarding one too. I had some hard rules: we wouldn’t add any new characters, we wouldn’t change the four-part structure, and the narrative arc had to be the same. Opera goers may be willing to accept a lot of poetry (and plot holes), but the same doesn’t go for graphic novel audiences. So we did expand upon it quite a bit in order for it to work as a graphic narrative, since we didn’t have the music to carry the action.

So, that included a lot more dialogue, some narration, and more backstory for the characters, who were more archetypal than three-dimensional in the original. One of the biggest changes is that I added an interlude in the middle, in which an executioner is struggling to execute a captured assassin. Both characters were introduced in the opera, but never revisited, and I felt like their side story–especially with all the baked-in irony–was worth exploring.

AO: Let’s talk about the collaborative process between the team. How did that work in bringing the world of Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis to visual life in terms of both storytelling and character design?

MAASS: Originally, I’d written the first chapter or so and put together a proposal. A few years back, I’d befriended Darick Robertson (Transmetropolitan, The Boys) and so I sent it his way. He warned me that I wouldn’t get very far with my pitch if I didn’t have an artist on board, and so I used queercartoonists.com to look for illustrators, and that’s when I discovered Ezra Rose, whose aesthetic, combining anti-fascism and Jewish mysticism, was perfect for the character designs. I’d met Patrick at Alaska Robotics Comics Camp a few years earlier, and so I asked him to take a crack at a page using Ezra’s designs, and he just knocked it out of the park. The instructions I gave to Ezra and Patrick is that everything in the book should have an origin, whether we base it on historical artifacts or are referencing modern day politics. What really brought it all to life was bringing Patrick to the Czech Republic, so he could draw inspiration from real locations.

AO: It may be several decades old but Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis feels horribly relevant in this time of growing authoritarianism and oppression. What do you hope readers will take away from its pages?

MAASS: The source material is so strong that it feels relevant over and over again. I first played with the idea of a graphic novel in the early 2000s, and I was making mental connections between the opera and the various wars and civil liberty erosions the U.S. was perpetrating. As I was pitching the book, Trump was in office, and then as Patrick was drawing it, Russia invaded Ukraine, and that created a sense of urgency. I hope that the book will help people process the difficult times we live in, recognize the perils of devaluing life, and remember that art can serve as a form of resistance long after its creators have perished.

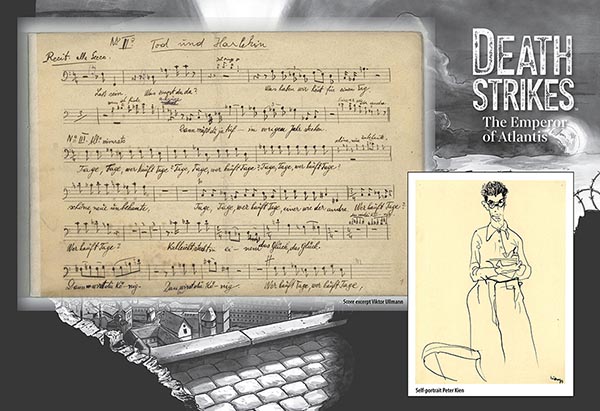

AO: The “extras” included in the book are simply remarkable, adding so much to the feeling of curation, preservation and commemoration that is so apparent in Death Strikes: The Emperor of Atlantis. Can you tell us a little about the research that went into the book?

MAASS: I am an investigative journalist by profession, and so I think I spent as much time tracking down the various threads of history as I did writing the book. It required communicating with people across multiple continents. I also had to find the original text of the opera to adapt, and it turned out that there were three different versions: a handwritten libretto, a handwritten score, and typed libretto on the back of prisoner records. I believe our book is the first time that pages from those three versions have appeared side by side. But among those three versions there were still disagreements, and so I had to dig in as deep as I could into Kien’s history to try to find clues about his original vision.

AO: And, finally, what else are the creative team currently working on, both in and outside of comics?

MAASS: Patrick has a few secret projects in play that I can’t divulge, but long term, he has plans to break into middle grade comics. Ezra worked on a really cool RPG inspired by Jewish mysticism called Beyond the Pale, which had a successful Kickstarter and is now available for pre-order. As for myself, besides promoting the graphic novel this year, I’ll be devoting a lot of time to researching technology being used at the U.S.-Mexico border in my day job at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Interview by Andy Oliver