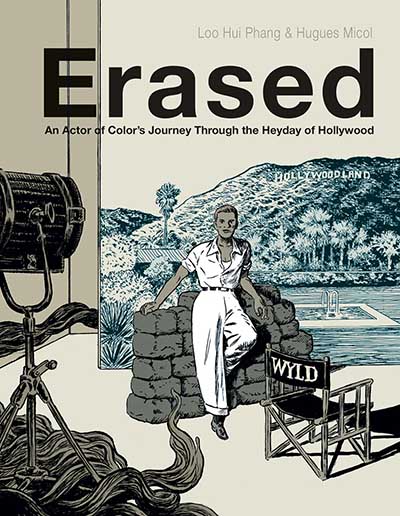

One of the most troubling notions to emerge from a reading of Loo Hui Phang’s powerful new graphic novel Erased: An Actor of Colour’s Journey Through the Heyday of Hollywood, translated by Edward Gauvin, is that although her story is set in Hollywood almost a century ago, we appear to be having the same conversations today.

The questions that emerge, time and again, seem as if they have always existed in some form: Does ethnicity define who can or cannot accept a particular role? Do studios genuinely care about representation? Is compensation fair, given how actors of colour routinely call out blatant discriminatory practices? What Phang manages to do, with the help of her fictional protagonist Maximus Wyld, is shine a light on forces that have long kept the spotlight away from minorities in cinema.

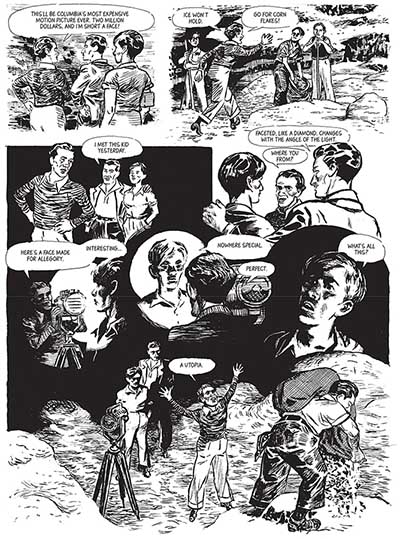

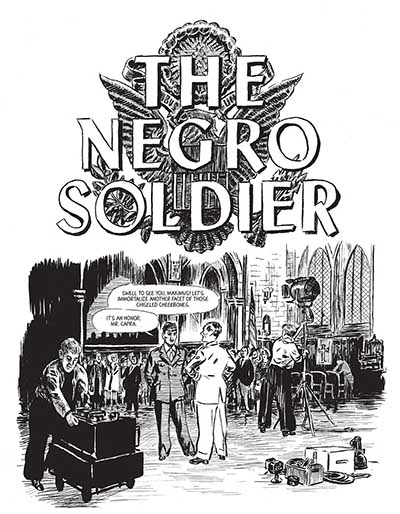

Wyld is a believable character not only because of the obvious amount of research that has gone into recreating his backstory. Phang also makes him flawed in multiple, nuanced ways, rendering him more human in the process. Add to this the cameos from real-life Hollywood stars, references to legendary films and roles, and one is transported into what feels like a solid work of non-fiction which, one suspects, is what Phang has wanted all along. It makes for a much more powerful work of fiction.

A mixed-race actor, Wyld plays all kinds of characters of colour, beds famous women, and tries his best to change the Hollywood machine from within. He is a powerful, subversive figure but, ultimately, isn’t strong enough to stay in the fight and is brought to heel by a scandal. The implication, however, is that the presence of people like him has long paved the way for actors of colour to emerge. We are asked to consider how, without a Wyld, there would be no Sidney Poitier.

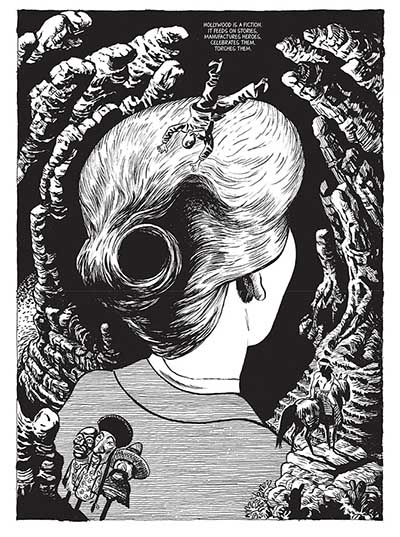

This isn’t to say there are no flaws in this narrative. For every carefully etched portrait of someone we believe we know — the actor Paul Robeson, producer Louis B. Mayer, or director Frank Capra, among other famous figures — there are asides that teeter on the edge of sermonising. Phang obviously has a message to get across, but the delivery is sometimes forced. Despite these hiccups, this is still a great story with an important moral, helped along greatly by Hugues Micol’s art. He packs extraordinary depth into his black-and-white sketches, be it with depictions of film sets, recreations of famous scenes familiar to all film buffs, or caricatures of stars. A particularly fetching series of panels mirrors the ‘flash dance’ techniques of the Nicholas Brothers, who rose to fame in the 1930s.

Erased almost reads like an exposé in parts, an insider’s account of the ways in which the process of marginalization can become a systemic problem that takes a century or more to undo.

In a recent interview, Phang expressed a wish that people of colour who had been exploited, and had their image stolen from them, would “cease to be objects and become human beings once again.” Ultimately, one of the most important things this book does is make one reconsider the men and women who ought to have had their share of glamour but were denied it simply because they weren’t the right colour. There may be no resolution in sight yet, but that dialogue continues, for which we ought to be grateful.

Loo Hui Phang (W), Hugues Micol (A), Edward Gauvin (T) • NBM Publishing, $24.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira