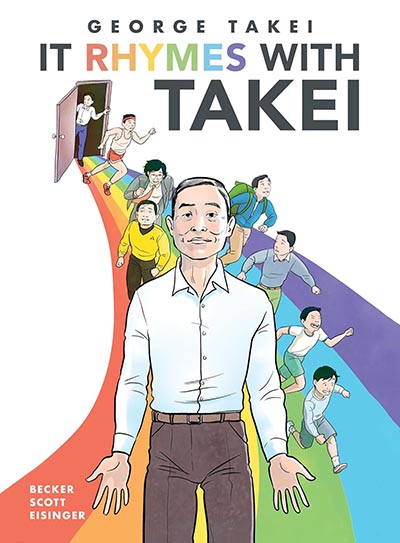

PRIDE MONTH 2025! George Takei played Sulu in the original Star Trek. In 2019 he published They Called us Enemy, a graphic memoir which tells how he and his family, along with more than 125,000 other Japanese Americans, were placed in internment camps by the U.S. government during World War II (reviewed here at Broken Frontier by Ally Russell Shields). It Rhymes with Takei, produced by the same team, is a full autobiography. It follows his progress as an actor and a political activist, and specifically it deals with the issue of his gayness, and the reasons he stayed in the closet for so long.

In the early 2000s, a Tennessee politician tried to ban teachers from using the word “gay”. George was out of the closet by then, and he suggested they could use the word ‘Takei’ instead, as a means of circumventing and ridiculing the ban. “Gay” rhymes with “Takei”, and this is one meaning of the title It Rhymes with Takei. But he goes on to explain that for most of his life he has lived in a state of semi-deception, presenting the public with a persona which rhymes with his true self but also conceals certain aspects. Only now that he’s openly gay can he open up his “closet filled with anxiety” and become “the whole George Takei”.

If you come to this book hoping for lots of juicy Star Trek gossip, you’re in for a disappointment. Star Trek is central to George’s acting career, but he doesn’t dish any dirt about the series. He’s clearly very close to Nichelle Nichols (Uhura) and Walter Koenig (Chekhov). He admires Leonard Nimoy, but from more of a distance. Without saying so in plain language, he manages to convey that William Shatner is a great big show-off. Interestingly, he never even mentions DeForest Kelley. The one he devotes most time to is Gene Roddenberry, the series creator, who he credits with almost visionary ideas about the future.

The book is more than 300 pages long, and it could have done with pruning by about a third. In his early twenties, for example, Takei visited Europe. Rome: “My favorite piazza was the magnificent Piazza Navona… Of course, all tourists in Rome visit the ruins of the Coliseum and the Roman Forum…” Paris: “Europe’s crowning jewel is often considered to be Paris. The city is a treasure trove of timeless art.” There’s rather too much of this kind of swotty culture-vulturing and bucket-list ticking, and it detracts from the central themes of the book.

One of those themes, politics, can also be heavy going at times. Parallel to his acting career, George has a history of political campaigning from the 1960s onwards. In the 1970s he became involved in planning urban transport in his home town of Los Angeles. He set out “on building a modern heavy rail rapid transit subway system in Los Angeles… It was essential to making Los Angeles a strong urban centre, but also to addressing air pollution, traffic congestion, and land use issues.”

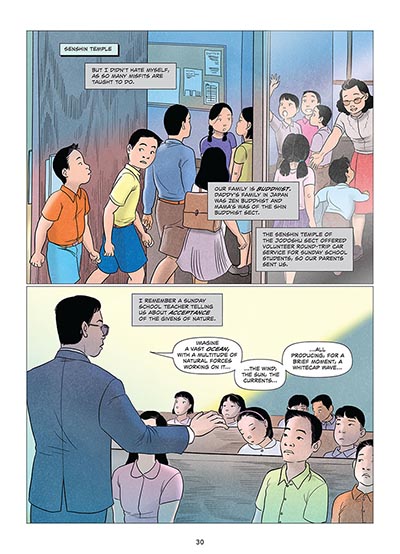

At least it’s clear in this section, however, that Takei cares about his subject and is genuinely proud of his achievements: and it’s obvious from the book as a whole that his engagement with politics runs much deeper than mere political correctness. Early in his acting career he becomes involved in a theatrical production called ‘Fly Blackbird!’, which deals with racial equality and reflects the 1960s civil rights movement. One of the main things that excites him about Star Trek is that it depicts a starship with “a diverse, multi-racial, multi-species crew”. Later on he helps to found the Japanese American National Museum, he raises funds and awareness on behalf of AIDS victims, and he campaigns for same-sex marriage.

Always a campaigner, Takei seems to have become more outspoken on political issues since he came out as a gay man. Coming out, in fact, provided him with a platform from which to speak his mind on the things he cares about, especially LGBTQ rights.

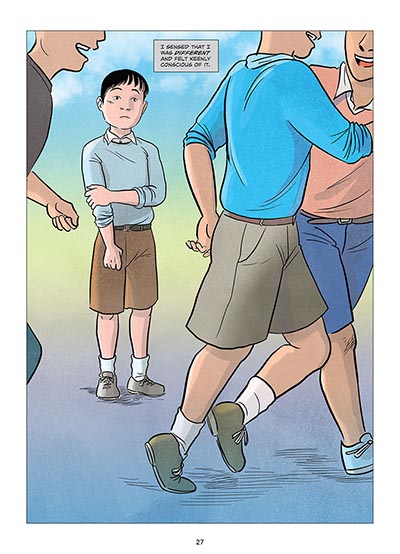

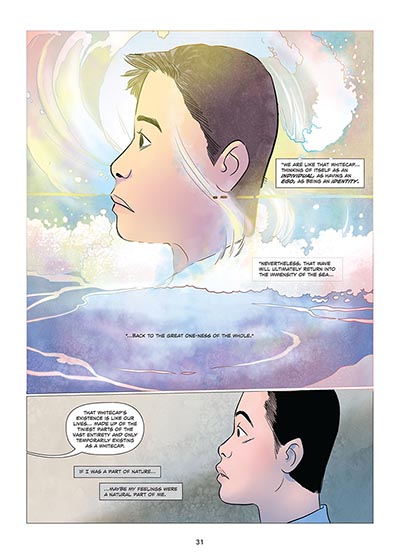

But as he says in the introduction, he didn’t come out until he was 68, and much of the book is therefore devoted to his time in the closet and his reasons for staying there. Homosexuality wasn’t completely decriminalised in the US until 2003. Gay clubs were often raided, and gay men beaten up or arrested or both. Being outed as gay could also ruin your career. Much of George’s story is about him repressing his inner nature, and feeling bad for doing so.

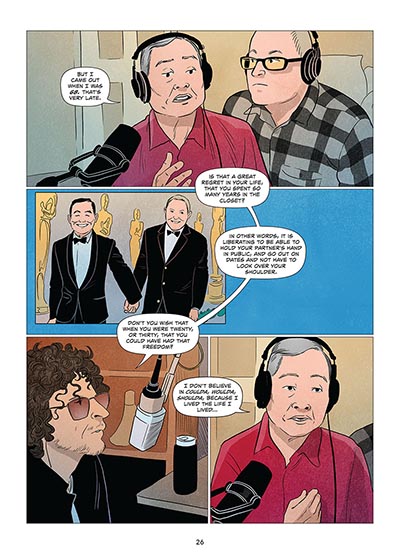

There are several episodes where he attempts to hook up with somebody – picking up another man in the library, or venturing into a gay bar – only to get cold feet and back out. He does manage to form some fleeting relationships, but it isn’t until the 1980s when he meets the love of his life, Brad Altman, and really finds his feet as a gay man; and even then it’s another twenty years or so before he finally comes out of the closet – a shrewdly managed disclosure via the Howard Stern radio show.

Ironically, it then emerges that his sexuality was more of an open secret than he supposed. In a subsequent interview, Howard Stern says “Everyone in America knew that George Takei was gay… Deaf people knew, blind people knew… I got a letter from the Pope himself…”

George also tells the story of how he misses his plane to a Star Trek convention and ends up having to share a room, and a double bed, with Nichelle Nichols. She tells him “Get yo’ body in this bed – I know you’re not going to do anything”. Clearly she recognised his gayness without him realising it.

On the other hand, when George’s brother hears the news, he first tells him he’s got to stop seeing Brad, then becomes furiously angry and refuses to have anything further do with him. This is one of the most vivid episodes in the book. Another is when, at the beginning of the AIDS pandemic, George goes to visit a friend of his who has caught the disease, and finds him shut up in a small room like a cupboard, covered in sores and shivering on a bed with no blanket, because the hospital nurses are so contemptuous of his illness.

The art can be pedestrian at times. George’s story is full of celebrities (Richard Burton, Cary Grant, William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy of course, and even Donald Trump) and some of the likenesses are distinctly iffy. There’s also a lot of wordiness: panels overcrowded with speech balloons, which are themselves overcrowded with explication. But Takei himself comes across as a very real person – proud of himself in some ways, timid in others, witty and humorous, acutely aware of his ethnic heritage, powerfully triggered by injustice, very focussed on the importance of love – and through his eyes we see the unfolding of several decades of American cultural and political history, particularly the history of the gay rights movement.

George Takei (W), adapted by Steven Scott and Justin Eisinger (W), Harmony Becker (A) • Top Shelf Productions, $29.99

Review by Edward Picot