One of the many delightful things about Tove Jansson’s legendary Moomins is how the series is often recommended online for readers between 7 and 9. This is amusing when one considers the joy her weird and wonderful creatures have been giving people of all ages for three quarters of a century now. There’s also a twisted logic to this categorisation, given how nothing about the Moomin world conforms to one’s expectations. To read their stories is to suspend disbelief, then recognise the absurdity of how we live our own lives.

Seventeen years ago, Drawn & Quarterly were the first to publish the Swedish comic strip in English since their appearance in a London newspaper. The publishers don’t need to justify why a new series has begun to roll out but, to their credit, they list some pretty compelling reasons. There is the acknowledgment of Jansson as a queer icon, recognition of her work as a subversive look at life under capitalism, and recognition of the Moomins’ appropriation as symbols of antifascism.

Moomin Adventures, the first of five planned volumes, collects seven of Tove and her younger brother Lars Jansson’s stories. There are familiar classics here, like ‘Moomin’s Desert Island’, as well as a couple of lesser-known tales, which makes sense given that this is meant to bring in a new generation of readers. For those familiar with Moominvalley and its family of lovable trolls, there may be trepidation about whether the stories hold up after all this time. Spoiler alert: they do.

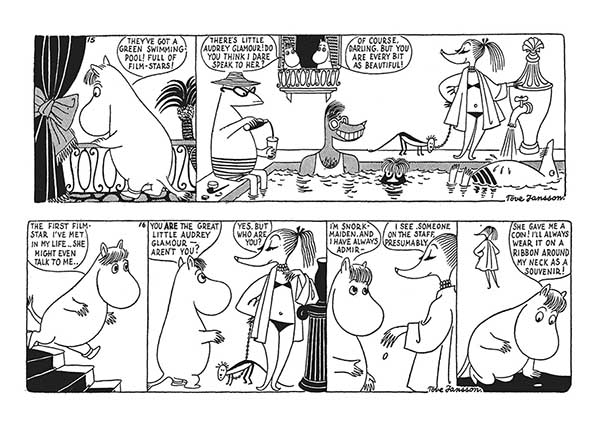

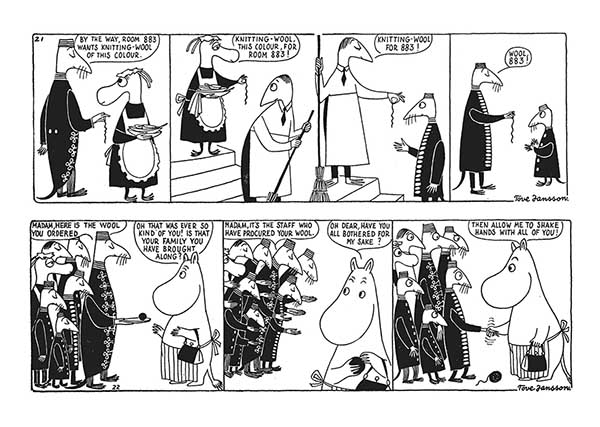

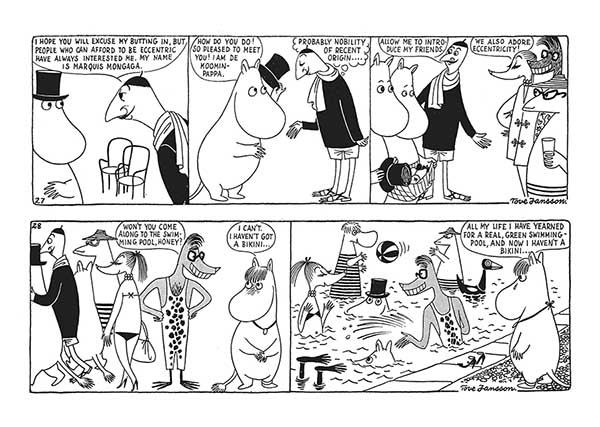

To try and pinpoint what makes the Moomins so endearing isn’t as easy as it may appear to be, because despite their mildness of demeanour and the softness that Jansson wanted to convey, there are some hard questions raised within these panels, about society, love, and how the world treats anyone it considers an outcast. Take ‘Moomin on the Riviera’, for instance, an effortlessly funny story of a family trip that doesn’t go quite as planned. There are some sly asides here, about the cult of celebrity, divisions created by widening economic gaps, and the artificiality of relationships built solely upon notions of class. The story inspired an animated film a decade ago, but the original comic loses none of its potency because of how little has changed. One can almost imagine the Moomins stopping by the next Cannes Film Festival and behaving in exactly the same way.

There is also an air of melancholy that pervades these pages, a reflection not only of Jansson’s grief in the aftermath of World War II, but what one assumes was a general state of anxiety during the years in which she created her comics. Much has been written about how some characters are psychological portraits of the artist and people in her life, but those biographical details mean little to first-time readers who may simply be charmed by their sheer eccentricity. How is one to explain why the Moomins try and live like Robinson Crusoe, choose to dig up their ancestors, or change their plans instantly according to the whims of family members?

Ultimately, why the Moomins continue to entertain us matters less than what they stand for — their respect for familial bonds, love of nature and simplicity, and ease with which they welcome everyone. In a world that continues to sacrifice human rights on the altar of shareholder profit, they still represent the possibility of something more meaningful that we all have access to. Reading them, it feels for a little while, that all we must do is try harder.

Tove Jansson & Lars Jansson (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $22.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira