When Canadian cartoonist and musician Geneviève Castrée passed away in 2016 at age 35, she left behind heartbroken friends who had long recognised her genius, as well as an audience that knew her only from the publication of Susceptible in 2013. There was much more she accomplished in her short life though, from books in French to a significant amount of music, and art across media.

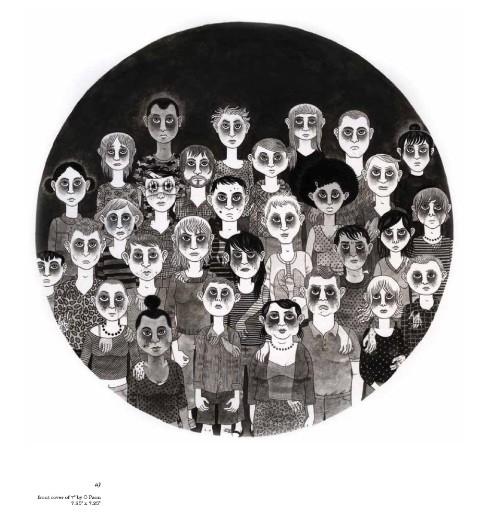

It fell to her husband, American musician Phil Elverum — to whom she was married from 2004 until her passing — to try and give shape to her legacy by curating everything she put out, as well as what she left behind. The result, Geneviève Castrée: Complete Works 1981-2016, is a loving, powerful tribute to an artist who deserves more attention.

We asked Elverum about the task of curation, how his late wife felt about responses to her work, and what he hopes to do with her art going forward. Here are his responses.

BROKEN FRONTIER: Your foreword has an interesting way of describing how Geneviève made her way through life, when you say she “chose the path of most resistance.” Is that how you would also describe her as an artist?

PHIL ELVERUM: Definitely. She did things the hard way. (By the way, I stole that line about her from her friend/publisher Benoît Chaput.) She valued the slow processes and not taking shortcuts. This often led to frustration and difficulty for her, being late on deadlines, having very high hopes for all the people around her and their ideals, being unable to match the huge flow of inspiration to the ability to physically manifest the ideas. The work in the book, the work that actually got made, was a small fraction of the ideas that she intended to ultimately pursue had she lived longer.

BF: Some of the standalone drawings — the series titled Le Canard Dans Mes Pantalons, for instance — seem as if they were supposed to fit into something larger but eventually didn’t. Were there plans to develop some of these or were they examples of the many abandoned bits and pieces you speak of?

ELVERUM: Yes, I included many unfinished projects in the monograph. She would sometimes abandon things when they were almost complete, or maybe complete something and never publish it. For the monograph I felt it was worthwhile to see it all, even if some of the works didn’t function as narrative stories or anything. (And actually, there are plenty of unfinished things that I decided to leave out, I was somewhat selective.)

BF: Anything labelled ‘Complete Works’ must inadvertently contain things an artist may or may not have expected an audience to see. Was there anything you were wary of putting out?

ELVERUM: Oh, for sure. I bet Geneviève would hate that I released probably a majority of this stuff. I sat with that question for a long time. During her life, I always told her how much I loved her sketchbooks, for example, and thought they should be published. She was driven to publish only “finished” things, but she did acknowledge that the sketchbooks were beautiful in their own way and obviously she worked hard on them. I think she secretly liked the idea of people discovering a vast trove of beautiful secret work after she’d died, although of course she assumed that would be much, much later.

BF: There is an interesting homage to Tintin in the form of Wœlv en Hiver, the fake record cover for a group exhibition of non-existent albums. Who were the artists or comic creators that Geneviève routinely turned to or read?

ELVERUM: Well, being a kid growing up in Montreal in the 80s, she was deeply raised by Hergé, plus Mafalda, Asterix, Smurfs, etc. Those big Casterman books. She was the hugest Tintin nerd. Tintin In Tibet was a central book for her and references to it run through all of her work. But that’s just the childhood stuff. After adolescence the influences broadened when she discovered the alternative comics world in Montreal and beyond, Julie Doucet for sure, but by then I think her own style was pretty well established. That’s kind of where the monograph begins.

BF: An interesting aspect of any collection arranged almost chronologically is how it reveals an artist’s state of mind. Some of her later work, like the Aokigahara series, seems more self-contained and succinct than the early drawings. Did you notice that too?

ELVERUM: Yes, that’s true. Those later years, not counting Susceptible, she was mostly making work for specific gallery exhibitions, not so much for a publication. Like, series of paintings and sculptures, things that could stand more on their own rather than be read in a narrative context. Even still, within the short painting groups, there was storytelling happening and interconnected threads. But yeah, I think of those years as the “art shows in galleries” phase.

BF: Do you foresee a home for the collages she made in her later years? A permanent exhibition of some kind?

ELVERUM: I actually still have pretty much all of the originals of everything and I’m still contemplating what to do with it all. It’s a difficult decision. At the moment, they’re all sitting in my house, arranged in binders. Now that the book is made, I feel like it’s time to send these things into the world in a way so that more people can see them. Seeing the originals is pretty powerful. The level of insane detail is hard to convey through any printing method. A permanent exhibition would be amazing. But yeah, the collages… I had an idea of maybe publishing the collaged tarot deck as an actual deck of cards. Maybe I’ll get around to that eventually.

BF: Work like ‘Blankets Are Always Sleeping’ has received a lot of attention, along with Susceptible, of course. Did you ever get a sense that she would have liked more attention for some of her other work?

ELVERUM: Yes, that was an ongoing struggle for her. I tried to address it a little in my introduction by talking about how she did things her way (the hard way), singing and writing in French but living in an almost exclusively English-speaking place, making deeply immersive but strange worlds of art and music but totally on her own terms, etc. She had a deep idealistic aversion to the types of attention-seeking that have become normalized with the ways social media has devolved our ways of interacting. So… yeah, she felt overlooked often and it hurt her, but also, she wasn’t willing to do the embarrassing work of hyping herself up in the crass ways that would actually work in our current world. She felt that the work should speak for itself, and that people should meet her there, which I agree with. I hope this book can do that.

BF: If there was one thing about Geneviève’s work you would recommend as an introduction to new readers, what would that be?

ELVERUM: Probably Susceptible. But she actually didn’t publish that much in her lifetime and it’s pretty much all in this monograph. So maybe I would recommend just this whole huge thing.

Buy Geneviève Castrée: Complete Works 1981-2016 online here

Interview by Lindsay Pereira