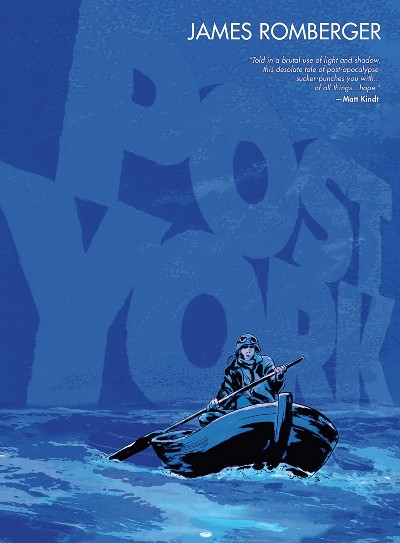

Post York is a graphic novel of few words, but its concerns are neatly summarised by its epigraph: Michel Foucault saying how “man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end… to be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.” Although this extract from The Order of Things originally revolved around theoretical discourses of epistemics, Post York uses it a little more literally. Set in the specific setting of New York, in an unspecific future, the streets of New Amsterdam have become flooded due to climate change, the tall skyscrapers that signalled civilisation’s dominance now dwarfed by encroaching nature. Mankind is a temporary blip upon the Earth, and now they are being dissolved back into its waters.

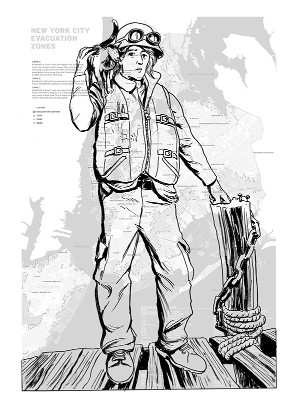

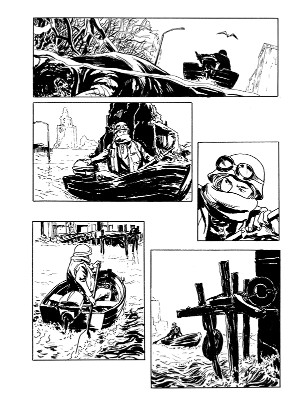

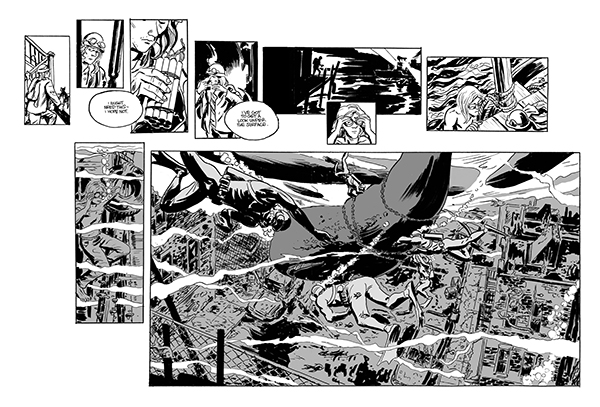

Still, some survivors are floating along the surface, like Crosby, who politely scavenges through dilapidated buildings (not wanting to steal too much of others supplies). This isn’t the anarchic bandits of Waterworld, which one group mock in an abandoned cinema, but one wherein individuals survive as best they can. Romberger renders serene scenes of Crosby sailing through the drowned city, such expansive silent panels combined with quiet sequences of Crosby tying knots and mooring his rowboat. He employs informal panelling – the black and white “water” bleeding onto the page, or other panels seeming “missing” – to establish a sequential looseness, delivering an atmospheric snapshot of Crosby’s world instead of narrative tightness. Romberger gorgeously draws this with fine fluid art-work and heavy black brush marks, lending Post York a European elegance reminiscent of Hugo Pratt. The environment is gruesome, of course, containing scenes of skeletons of corpses being ravaged by sharks. But in its opening moments, Post York imbues a beautiful tranquillity to the melancholy of being alone in an enormous city. That is, until Crosby gets in an altercation with another survival while rifling through her room. Crosby manages to escape, only losing his helmet, but it’s a confrontation Post York will return to. Literally.

See, after Crosby continues his day (freeing a whale trapped amongst his sunken building’s foundations), a giant page of “OR” appears, and Post York returns to that altercation with a different, more tragic, outcome. Post York has three “alternative timelines.” If the first is more tranquil, even triumphant in Crosby’s saving of a sea-mammal, the second is far more vindictive and brutal, an “accident” rippling out into acts of violence. Meanwhile the third story, caused by a leak in Crosby’s boat, is more talkative, bitter and polemical, concerning the characters watching the whale Crosby saved (in another timeline) be butchered by “rich people in their floating city.”

Post York’s narrative gamble of alternate timelines is an interesting one, but not one which entirely pays off. Romberger explained in a press-release that Post York was “improvised directly onto the art boards without script of preliminary layouts,” yet unlike Blue in Green (which had a similar creative process), Post York is not about improvisation or chaos theory. The narrative “resets” occurring around two entirely different events also makes the conceit feel underdeveloped, and each strand disparate. It doesn’t help that such “resets” distract from the characters of Post York, and unclear what Romberger was aiming for. Indeed, the more action-orientated latter storylines make Post York hew closer to Waterworld than was likely intended.

Yet, despite this muddiness, something about this creative choice lingers. One character, Stuart, paints a fresco mural upon the ceiling of the abandoned theatre, despite knowing the rising water-levels will eventually submerge it. “Nothing lasts forever,” he explains, but this impermanence of mankind (and its creations) is juxtaposed Post York’s narrative time-loops. It’s as if the story is seeking ways to avoid progression, even if heading for the same inevitable end. Perhaps the larger question Romberger is interrogating is whether humanity’s future is fixed, or can we still change our story? Scientific research upon climate change included in Post York’s appendix (and the fact Crosby is modelled after Romberger’s own son) shows this is more than a passing concern to him. Post York is never quite as convincing as its introspective opening moments, the dialogue and plot incomparable to the serene mood of his lovely artwork. But Post York manages to touch upon some meaningful ideas and gorgeous sequences, despite the murky waters surrounding them.

James Romberger (W/A) • Dark Horse Comics/Berger Books, $17.99

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong