“Girls like you…men just want you for your body. I’m a man. I would know.” The comment raises all kinds of red flags, for men as well as women, because of the many implications that can be drawn. Weng Pixin places it in the mouth of a mentor from her protagonist’s past, someone she refers to simply as ‘T.L.’ It is important to refer to the person as a protagonist, rather than Pixin herself, because fiction can be used to create a certain distance without which the act of honest retrospection becomes difficult.

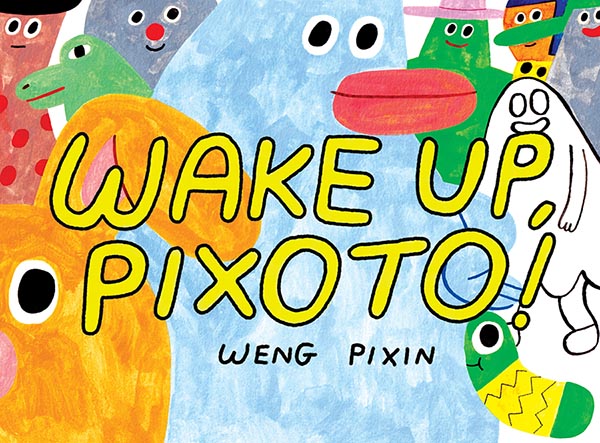

Wake Up, Pixoto! is a careful act of remembrance, a sifting through of memories that is deeply personal, painful, and necessary. It serves to examine the relationship between the artist as a young woman and a mentor or friend with questionable motives. Like all complicated relationships, things aren’t as easy to define as they seem, despite the problematic nature of the comments that T.L. routinely makes. This is a relationship between an older man and a young woman, and Pixin reveals the thin, subtle line between genuine mentorship and the imposition of control.

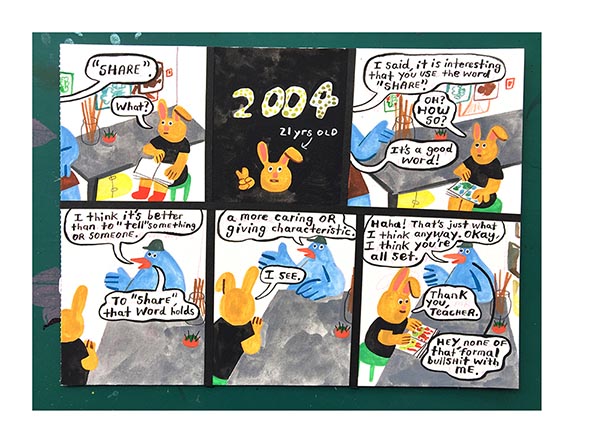

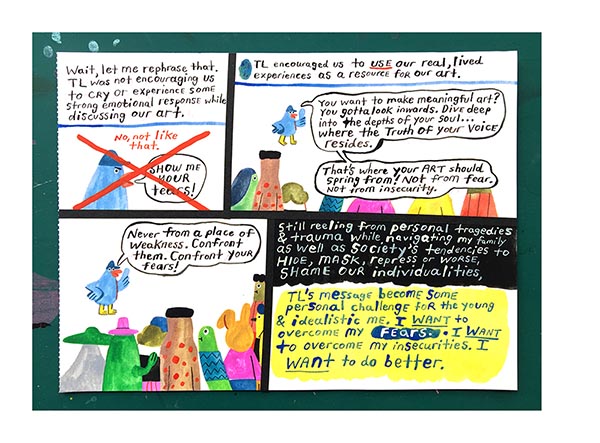

Set in 2004, it is a memoir about a 21-year-old art student and her friendly teacher who starts to exercise an unhealthy degree of authority over the former’s personal life and choices. Pixin uses a rabbit to represent the student, and a blue bird in a hat to stand in for her mentor. What does T.L. want? Are his intentions healthy? Is he merely misunderstood? These questions are valid because of how they tend to crop up in any relationship that borders on grooming.

When it comes to adult grooming, the act involves the same psychological processes used on children, preparing them for behaviour that is either abusive, manipulative, or exploitative. It involves the gradual building of false trust, and what makes it harder to recognize is the fact that groomers sometimes delude themselves as well as their targets, failing to self-identify.

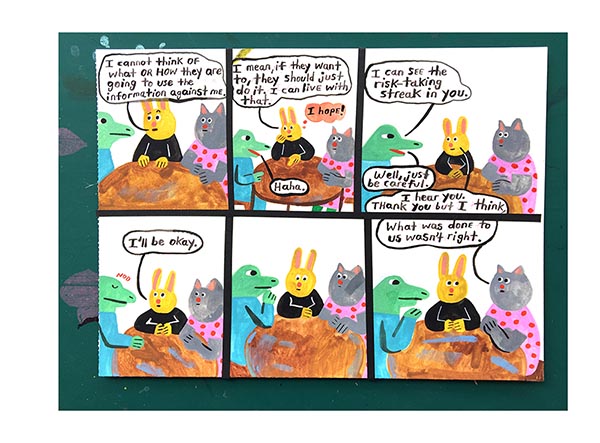

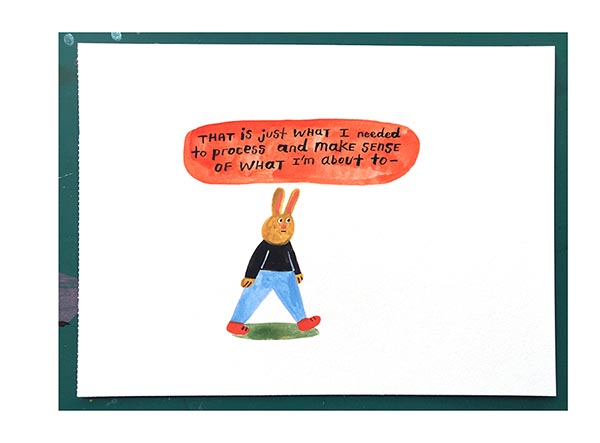

Psychologists also point to two elements involved in this act, of intent (wanting something other than what is stated or offered) and consent (questioning whether the victim would make the same choices with awareness). Pixin examines both elements, by trying to see these events from multiple sides. Her story becomes powerful because of how her now-recognisable bright and bold style is offset by extremely perceptive comments about what the art is depicting. For example, one panel features the FAQ: “Why didn’t you leave, Pixoto?” Her answer, printed upside down, refers to respect and trust, and includes an explanation from the survivor of a cult who points out that victims resist questioning groomers because they are often responsible for fond memories of love and friendship.

A few years ago, while being interviewed by the Los Angeles Review of Books for Let’s Not Talk Anymore, Pixin pointed out that one of the things she was interested in exploring was a person’s capacity to attend to others’ emotional needs. With hindsight, it is easy to see why someone who has experienced grooming would cultivate empathy and gravitate towards trying to understand another position.

Pixin asks tough questions of the young art student, and it is her careful attempts at answering them herself that makes Wake Up, Pixoto! so relatable. It also shows that while toxicity in a relationship can come in many forms, the antidote almost always lies within us.

Weng Pixin (W/A) • Drawn and Quarterly

Review by Lindsay Pereira