“It was just a colour out of space—a frightful messenger from unformed realms of infinity beyond all Nature as we know it; from realms whose mere existence stuns the brain and numbs us with the black extra-cosmic gulfs it throws open before our frenzied eyes.”

H.P. Lovecraft is one of the most famous and influential of American horror-writers, but his style is by nature very difficult to translate into a graphic novel. His stories tend to be long on “atmosphere” and short on everything else. Characterisation and dialogue are minimal. Plot developments and dramatic incidents can be few and far between. He builds up a sense of malevolence and unease layer by layer, usually starting with legends, stories or rumours, then gradually taking us closer to an inner truth to which these point. But even when we get to the heart of his stories, he still very often leaves us mystified as to exactly what’s going on. At the moment of climax, his writing explodes or collapses into outpourings of numinous description – “frightful”, “unformed”, “infinity beyond all Nature”, “extra-cosmic gulfs”, “frenzied”. The language is gestural. It doesn’t actually describe anything we can visualise or intellectually grasp, and it isn’t meant to. It’s trying to suggest something beyond the boundaries of understanding.

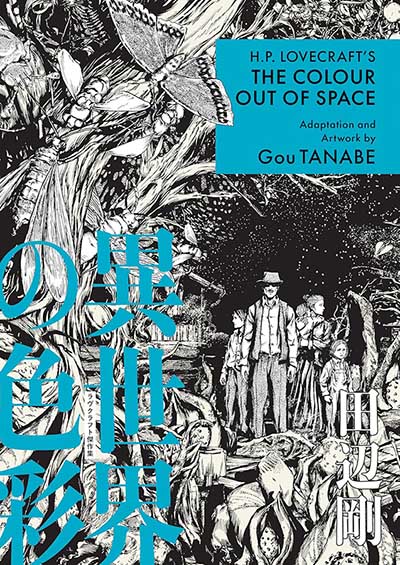

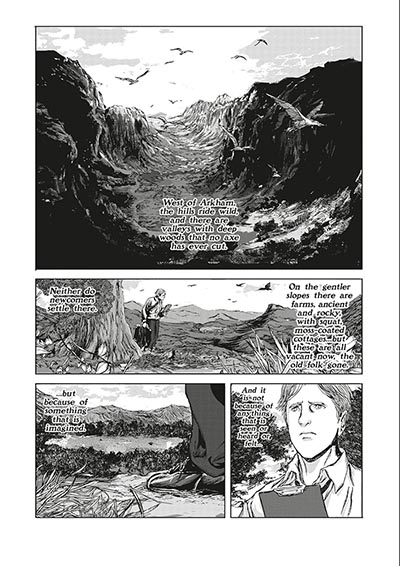

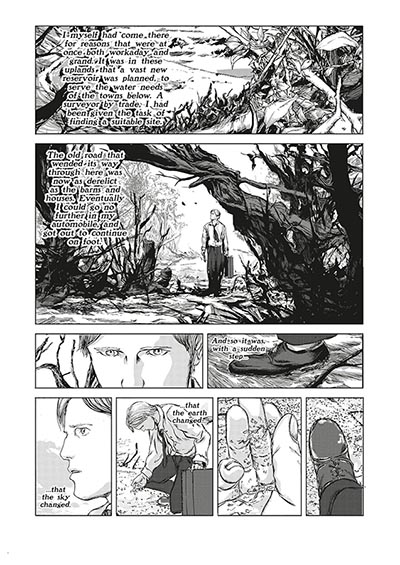

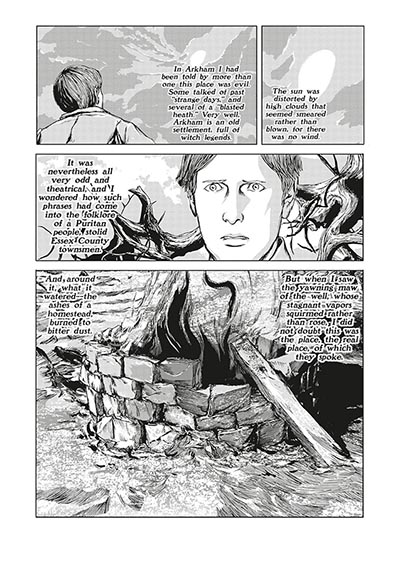

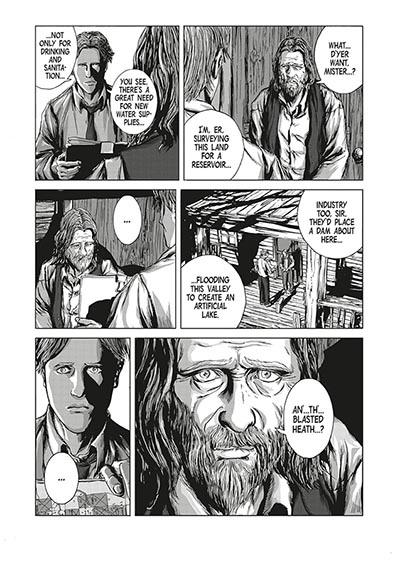

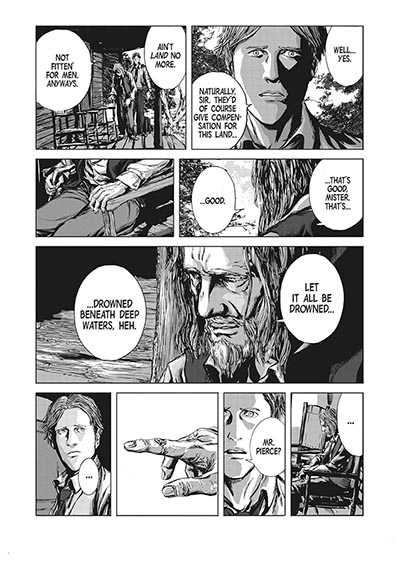

The Colour Out Of Space (1927) is one of the best-structured of Lovecraft’s stories, and Gou Tanabe’s adaptation follows that structure closely. A nameless surveyor (the story’s narrator) has been sent to scout an area near Arkham, which is scheduled to be dammed and flooded to create a reservoir. The area is known to locals as “the blasted heath”, a title which he finds ridiculously theatrical until he actually visits the place, and finds it not only blasted but sinister. The one person still living in the area is an old farmer named Ammi Pierce. The surveyor visits him to ask about the history of the heath, and Pierce unfolds the story of how it came to be poisoned and deserted.

Years before, when Pierce was young, a meteorite fell close to the house of his neighbour Nahum. Scientists came to investigate the meteorite – and when they gouged into it, they discovered a “globule”, of a colour “almost impossible to describe”. “One of the professors gave it a smart blow with a hammer, and it burst with a nervous little pop”.

From that point onwards, it starts to become apparent that the meteorite has brought some kind of baleful life form to earth with it. It gradually puts a blight on Nahum’s land, his livestock and his family, and the distinguishing characteristic of this blight seems to be the peculiar colours it creates: “All the orchard trees blossomed forth in strange colours… everywhere [there were] hectic and prismatic variants of some diseased, underlying primary tone without a place among the known tints of earth…”

How do you depict an impossible colour in a graphic novel? Tanabe’s solution, perhaps counter-intuitively, is to draw the story in black and white. The unknown colour is represented by areas of shimmering, swirly grey, which work surprisingly well: they don’t make us feel disconcerted, threatened or queasy, which are the effects they have on the characters in the story, but they do make us feel as if we can’t be quite sure what we’re seeing. And the most effective way of depicting the colour out of space is the one Lovecraft uses himself: not showing it to us directly, but showing us its effects. Some of the drawings of mutated plants, moths, animals and people are genuinely creepy.

According to Wikipedia, “Lovecraft was dismayed at the all-too human depiction of aliens in other works of fiction, and his goal for ‘Colour’ was to create an entity that was truly alien.” The same source also suggests that the story may have been influenced by “coverage of the Radium Girls scandal in The New York Times, with the symptoms… matching the newspaper’s description of radium necrosis”. You can certainly read it as an early warning about the dangers of radiation, or as a tale of environmental collapse.

Another obvious point of reference is H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897), which also begins with the arrival of something thought to be a meteorite, which subsequently turns out to be carrying alien life. But The War of the Worlds is mainly based on the personal experiences of the narrator, who sees the aliens and the destruction they bring first hand, whereas Lovecraft’s story, characteristically, is presented to us by the surveyor, who retells a story he heard from the old farmer Ammi, and Ammi’s tale is mainly about what happened to his neighbour Nahum. In this way we are placed, as readers, at several removes from the main action. And whereas Wells’ aliens soon reveal themselves as unmistakeably warlike and merciless, destroying swathes of human life and property with their heat-rays, the effect of Lovecraft’s visitors is much more insidious, and it still isn’t plain at the end of the story whether they are deliberately harming the life around them, or whether they are simply poisonous by nature.

Some of Lovecraft’s deliberate vagueness and mysteriousness – his preference for hints and clues rather than explicit details – is lost when his story is translated into the graphic novel format. The characters are more individuated, if only because they’ve been drawn to look different to each other; and they’re given more dialogue, which in turn plays a more prominent part in the development of the plot. The friendship between Ammi and Nahum also seems more real in the graphic novel than in the story.

Another difference is that the story (about 12,000 words) is one undivided strip of prose, written in long paragraphs and only occasionally broken up by dialogue, whereas the comic book (nearly 200 pages) is divided into a prelude and six chapters. The effect of this is both to lay bare the structure of the tale – making it clear how the situation at Nahum’s farm goes step-by-step from bad to worse – and to make it seem crisper, less heavy going.

One interesting moment comes right at the end of the tale, when Ammi and a number of other investigators are fleeing from Nahum’s farm. Ammi is the only one to look back. “As the rest of the watchers on that tempestuous hill had stolidly set their faces toward the road, Ammi had looked back an instant”, writes Lovecraft. There is a reference here to the Biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah: Lot’s wife looks back as she and her husband are fleeing the destruction, and she is immediately turned into a pillar of salt. Lovecraft only suggests this reference, but Tanabe makes it explicit: “It was his soul, not his body, that turned to salt that night”. This exemplifies the way in which Tanabe is prepared to spell out some of the things Lovecraft prefers only to suggest.

It’s never possible to transpose a work of art from one medium into another without changing it, and the best adaptations are fully aware of these changes, but also of the qualities they wish to preserve from the original. Tanabe knows exactly what he’s doing in his adaptation of The Colour from Space, and the end result is a graphic novel version which does full justice to Lovecraft’s original, without leaving it entirely unchanged.

Gou Tanabe (W/A) • Dark Horse Comics, $14.99

Review by Edward Picot

[…] The Colour Out of Space (Edward Picot, Broken Frontier) […]

[…] Broken Frontier reviews Gou Tanabe’s “The Colour Out of Space” graphic-novel in its just-released English translation. Spoilers-alert (for those who haven’t […]