Julia Gfrörer’s Too Dark to See is a brief supernatural story that poses questions about our cosmic insignificance. In the face of creatures beyond our understanding what are the lives of humans? What are human emotions like love to creatures that do not experience them in the way we do… if at all? Usually the domain of pulpier fare, Gfrörer explores these concepts within the petty meager domesticity of a young couple. Rendered with a mix of thin controlled linework and violent cross-hatching, Gfrörer’s strong grasp of anatomy and excellent sense of staging pull us deeper and deeper into the darkness infesting the lives of Jaime and Lauren.

Julia Gfrörer’s Too Dark to See is a brief supernatural story that poses questions about our cosmic insignificance. In the face of creatures beyond our understanding what are the lives of humans? What are human emotions like love to creatures that do not experience them in the way we do… if at all? Usually the domain of pulpier fare, Gfrörer explores these concepts within the petty meager domesticity of a young couple. Rendered with a mix of thin controlled linework and violent cross-hatching, Gfrörer’s strong grasp of anatomy and excellent sense of staging pull us deeper and deeper into the darkness infesting the lives of Jaime and Lauren.

We begin with the couple together in their frameless bed, a single word balloon hovers high above them with the tail perfectly placed so as to cast ambiguity as to who is confessing their immeasurable love to whom. This moment of intimacy’s meaning immediately begins to erode as, while the couple sleep, a shadowy figure seeps in from the opposite corner of the room. This feminine silhouette silences Jaime and demands he have sex with her. He graphically complies and then resumes his slumber. The next morning Lauren comments on Jaime’s strange behavior during the night, but he claims to have no memory of anything that happened.

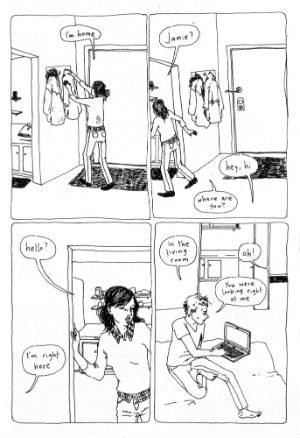

We then casually follow Lauren as she goes to work at a coffee shop until she returns home to find Jaime typing on their shared computer. The couple begin to fight over Lauren’s discovery of a black growth that she believes to be an STD; one that she is convinced she has contracted from an unfaithful Jaime. After he storms off, Lauren begins cutting at her wrists with a safety pin. She then lies down in bed, at which point a masculine silhouette emerges from the wall. We see Jaime return and call out for Lauren, but otherwise the story is unresolved; the final pages only hinting at the couple’s future as considered by the two silhouettes. The mocking way in which the silhouettes discuss the couple on the final pages a contrasting mirror to their declaration of love on the first.

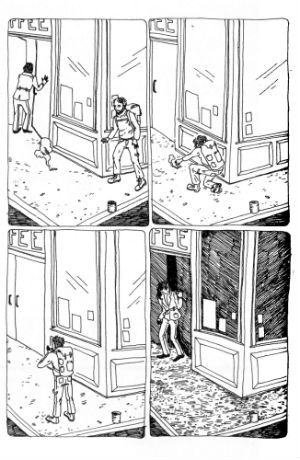

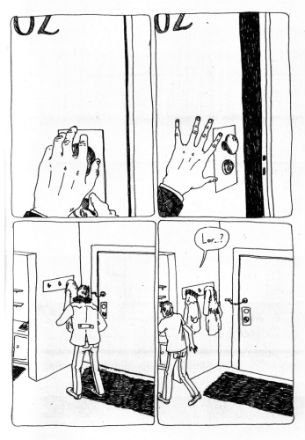

That so many things are left opaque is integral to what Gfrörer seems to be trying to do here thematically. The story is less about what happens and more about how we observe what happens. To the supernatural silhouettes human love and human lives are pathetic and this detached and alien way of viewing the couple is a major aesthetic within the storytelling. The camera is frequently placed observationally within the scene, holding its position to document the body language and movement of the characters. It lingers on the outside of the coffee shop to capture a backpacker coming around the corner and picking up Lauren’s discarded cigarette; zooming in on hands to observe actions such as cleaning a cappuccino machine, making a peanut butter sandwich, or Lauren mutilating her wrists, but it avoids faces.

In the sequence in which Lauren and Jaime fight over the unseen STD the camera is dispassionately set behind Lauren so that we never see her face as she cries. It records events in real time during the fight as Jaime goes to wash the dishes, an act which only heightens tensions. While the camera is slightly more dynamic in the way it records the sexual congress between the silhouette and Jaime, the event is depicted without emotion, focusing more on the mechanics of their intercourse. It is as if the story is being recounted to us by the silhouettes and is thus seen from their vantage point.

If events are indeed being told from the silhouettes’ point of view there are still deeper suggestions to decode from their final conversation. The silhouettes discuss potential baby names yet it is unclear whose baby is being discussed. In one panel the female silhouette asks, “what should we call it?” While in another the male silhouette jokes, “they’ll probably give it some grandpa hipster name.” Has Jaime impregnated the female silhouette? Has the male silhouette impregnated Lauren? Another question that goes unanswered is why does Lauren momentarily fail to see Jaime when she returns home? A phenomenon that is repeated when Jaime returns home after their fight and is unable to locate Lauren.

This intangibility and the potential shared pregnancy draw a parallel between the silhouettes and the couple. One couple is contrasted against the other in a way that seems to favor the silhouettes. The silhouettes are not locked in petty domestic squabbles over who does the dishes or who is interrupting the other’s work. They are not filled with jealousy and suspicions of infidelity, nor with insecurity about the other’s exes. They knowingly sleep with the human couple for their own amusement and laugh about it afterwards. This then becomes a story about humans interacting with the supernatural forces told with as little empathy for the humans as such otherworldly creatures would actually have for lesser beings.

This is not to say that Gfrörer is being nihilistic. While Jaime and Lauren’s lives may mean nothing to the silhouettes, we as fellow humans can sympathize with their situation. Jaime suggests that Lauren’s malady is showing up because her immune system is down from smoking. But his weakness and engagement in vice with the female silhouette has already brought darkness into their lives. It seems no accident that Lauren’s self-destructiveness conjures the male silhouette. The darkness waits for them to let their guards down before appearing. All of us have our own personal darkness lying in wait at the corner of the room for us to let down ours.

Julia Gfrörer (W/A) • Self-Published, $5.00

Available at https://www.etsy.com/shop/thorazos

Review by Robin Enrico