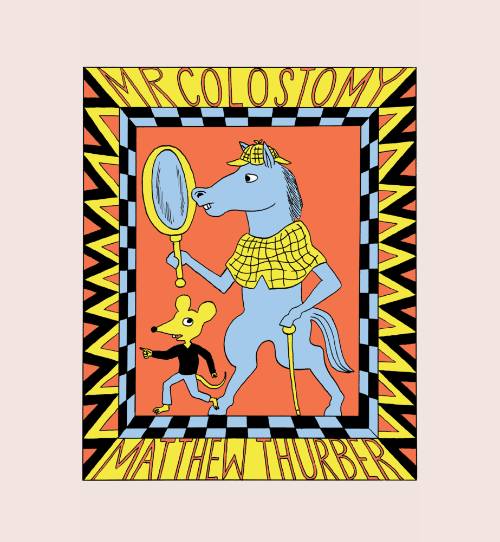

A colostomy involves the creation of an opening for the colon through the abdomen. The cartoonist Matthew Thurber refers to it as something in the body that passes out in a different way. It doesn’t fully explain why the protagonist of his latest book is a talking horse named Mr Colostomy, but creates an interesting context for an animal as the manifestation of something in his unconscious presumably trying to get out.

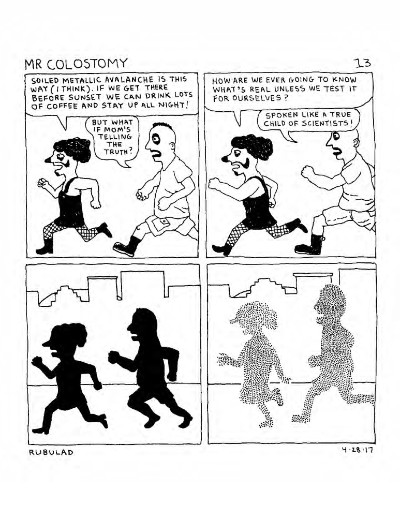

The book first existed as a serialized strip on Instagram and must be read with that in mind as meanings, connections, and narratives slowly accrue over panels and pages.

We wanted to know more about why Thurber chose a horse, what kind of audience he had in mind, and how the Covid-19 pandemic had an impact on his art. Here are his responses to our questions.

BROKEN FRONTIER: One of the interesting things about Mr Colostomy is that it often seems less surreal in a post-pandemic world. Was its somewhat sardonic tone a reaction to what you were experiencing over the past couple of years?

MATTHEW THURBER: I started making the comics in April 2017 as a daily ritual that lasted a couple years, so this book is from “the time before.” However, I think a lot of the concerns that the pandemic revealed or amplified were already apparent and are being talked about by the characters in the strip. I was just making jokes about what I was observing through a kind of journalistic practice. For instance, the alienation that I was struck by upon entering a coffee shop in which no one was talking to each other…didn’t seem normal to me or even human. Or the way that computer addiction encourages a sense of mental restlessness, a sort of insomnia even when you’re awake. Maybe it required funny animals to comment on this. Mr Colostomy and Groomfiend, the homeless anarchist mouse, are my comedians making remarks on a contemporary disintegration of spontaneous and honest civic life.

BF: There is a strong streak of philosophy running through the book, some of it almost deliberately obscure. What sort of audience did you have in mind while working on it?

THURBER: Thank you for perceiving it as philosophy. Jokes are for me a kind of philosophy in action and the goal of the comic strip was to make it funny. There is a philosopher in the book, Ersatz Oldman, who is a child wearing an obvious old man disguise. He is trying to re-write a philosophical treatise at the bar because his original one was destroyed by his roommate’s cat’s pissing on it. This is probably typical of me, to put a kind of philosophy into the mind of a character and to undermine it with humour.

When I was drawing/writing the comics, I felt like my characters were engaging in a form of Socratic dialogue, asking “why this?”, “why that”, over and over. For me that is not obscure but is (or should be!) an essential process and kind of the origin of scientific method as well as the part of Western philosophy I like. I think the book will appeal to anybody who, confronted with the world, can’t stop asking questions. Like “Where did all my money go?” or “What is Time?”

BF: Horses are associated with the sacred in some cultures, or with omens, or fertility. What compelled you to use this animal as your protagonist?

THURBER: My personal worship of the horse began when I first moved to New York and went to the racetrack in Aqueduct. I really like the bizarre names given to horses which are very abstract. I didn’t know what it meant but I started drawing this horse person around 2002. Mr Colostomy’s name is a non sequitur, almost. But a “stoma” also means a kind of opening for something in the body to pass out in a different way. To me this is a kind of metaphor for an alternative way of doing things. Mr Colostomy as a horse is an unnecessary and outmoded figure from an agrarian horse culture that disappeared with the automobile. My dream would be to go on a tour someday on horse. There is something about the horse that is truly mythological. Also, I am an animator and I’m always showing my students the series of Eadweard Muybridge photos of the running horse.

BF: When someone is described as a “multidisciplinary artist”, it’s usually a reference to restlessness with the perceived inadequacies of a fixed medium. What do you prefer working with, if there is a preference at all?

THURBER: Thank you for giving me the opportunity to say something about this. I have a very restless or unstable practice or “career” and I think that is okay and even good, but it has given me so much angst because other people seem so focused.

The most important thing is to love your work and to work (which is also play) daily. I like learning skills and that leads me into the position of the amateur, rather than the “professional artist” which is often a difference of definition, or of perception, fortune, or class. For instance, I just recently started making paintings, and I am disappointed in them. I feel I’m not understanding something, in the way that time-based media are easier for me. To have confidence to try something new is extremely difficult but you must try, and in the process of learning what is specific to a new tool or medium, it starts to affect the way you see other methods, and that is really why I make art, to learn.

My favourite tools include ink and dip pens, paper and books, typewriters and 16mm cameras and projectors, piano, and tape recorders. It all involves a use of imagination and to some extent montage or editing. Performance and filmmaking involve time and space, and so do comics, in a different way. Writing words is probably the practice that I engage in the most and started doing first.

BF: You have, in the past, referred to art as a spiritual process. Was your relationship with it affected by our state of lockdown?

THURBER: Yes, because the chips were really down! What else is going to save you? The Criterion Collection? Art is my meditation and therapy. Perhaps unfortunately, my devotional practice is drawing a comic strip with a talking horse. Making art is how I transcend my Self. I commune with my readers. I guess by art I also mean nature and God. While drawing the Colostomy strips I read a lot of John Ruskin, the art critic and big booster of Turner and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. He talks a lot about observation of nature in a very Christian language. I think he’s kind of a blowhard, but I like that in another way. A more ironic way. You can feel his asexual, nature-obsessed, paternalistic Victorian presence particularly at the end of the book. He just wanted people to look more to nature. And he didn’t like trains and thought the industrial revolution was crap. I will stand up and say I love his book The Elements of Drawing.

BF: The only social media platform you use with some regularity is Instagram. Why do you use it and what do you get out of it?

THURBER: I hope to leave it soon. It was the newspaper in which Mr Colostomy was syndicated.

For more on Mr. Colostomy visit the D+Q website here.

Interview by Lindsay Pereira