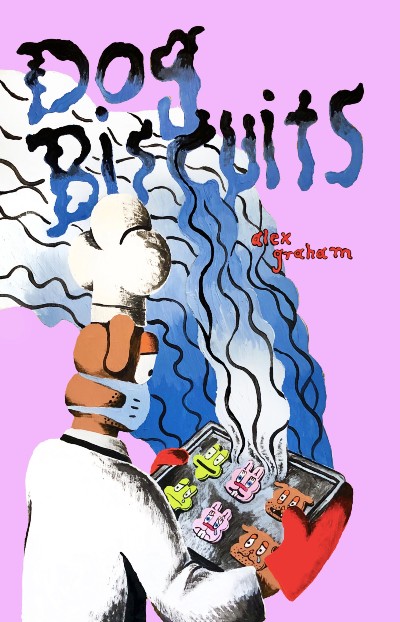

As Rosie (the Rabbit) puts it part-way through Alex Graham’s Dog Biscuits, “there are certain aspects of being alive that are impossible to control.” This is true of her hormonal lust and personal hang-ups pushing Rosie towards relationships she knows are destructive. Or on a larger scale, a global pandemic that make such relationships all the more delicate. Rosie’s complicated crush on her boss Gussy – not least because he’s a dog – is exacerbated both because of the difficulty of finding new work amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and the slower-than-usual artisanal dog biscuits store leaves the two plenty of time alone to fixate on each other. Plus, there’s the fact Gussy is twice Rosie’s age, inviting critiques from everyone who catches wind of their love-affair, including the two’s own persistent inner-thoughts. Both Rosie and Gussy consider how simpler things would be if their feelings did not exist, but some things are impossible to control.

Dog Biscuits came about when Graham “worked” at (and was later furloughed from) an empty bar, kept on due to a COVID loan while there were no customers, doodling a few pages a day and throwing them up on Instagram. Several comics have now been made “about” the pandemic, but Dog Biscuits was born from it in a unique way, and tackles the crisis through not making it the main focus. It’s an important aspect of these characters’ lives, but only one sliver as everything else continues. Dog Biscuits is packed with psychological truth and observations, imbued with a rich authenticity which is rare for any chronicle, let alone one apparently made on the fly.

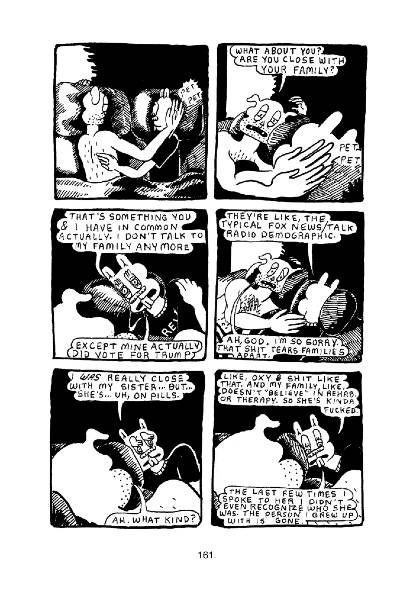

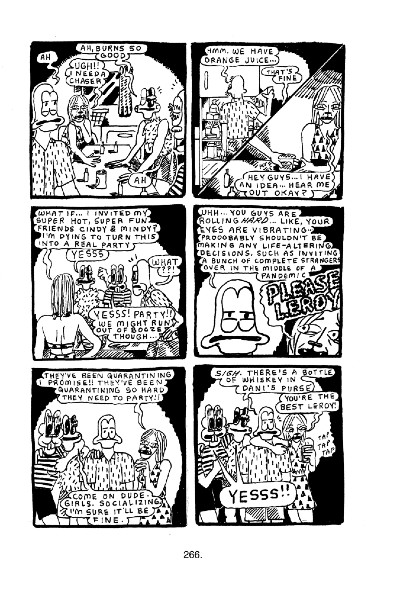

Indeed, it was odd learning of Dog Biscuits’ origins considering how seamless it reads, seldom leaning on webcomic cliff-hangers and instead organically expanding to tackle the complexities of modern life. Gussy and Rosie’s age-difference is shown through how he is primarily backwards-looking and she is mainly forwards-looking; while she delights in the retweets her viral video of a rude customer is getting, Gussy is concerned how it will impact his fledgling business. Other relevant topics like protests, police brutality, depression all naturally arise too. The improvisational development of Dog Biscuits may mean not everything comes full-circle, but this actually seems more honest to the slice-of-life focus that nevertheless keeps a core undercurrent on juggling complex commitments and the frustrating difficultly of expression

Dog Biscuits’ anthropomorphism is less coherent. Art Spiegelman’s Maus used animals as metaphors for ethnic nationalities (even if the metaphor purposefully broke down), and Dog Biscuits appears to aim at something similar in how most (but not all) of the “human” characters are female white “Karens” who complain to management or refuse to wear masks. Given the backdrop of “Black Lives Matter” protests, race is an important factor, but our main free animals seemingly identify as “white” leaving Dog Biscuits with barely any black people. Still it’s a minor complaint on a system likely made for the absurd image of Gussy (a dog) selling biscuits to humans with regular dogs as pets. Dog Biscuits is also a comic where Hissy (a frog) is randomly the son of actress Jennifer Love-Hewitt, often bending regular rules of reality even as it comments on relevant social issues.

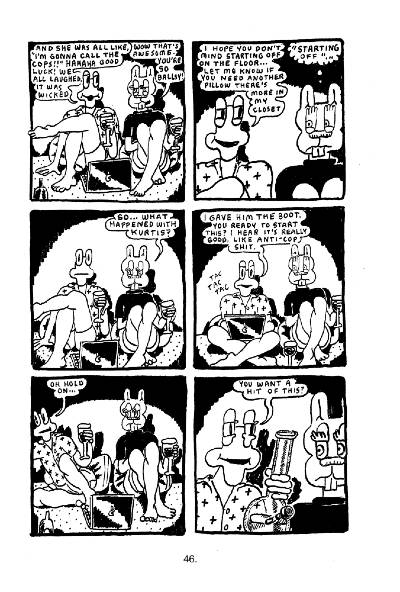

The casualness of humanoid animals, alongside its satirical commentary on modern life and self-destructive relationships, may call to mind Bojack Horseman. But Graham’s book recalls work like Fritz the Cat and the 1970s Underground Comix scene, with its self-published release, broad social satire (especially concerning police brutality) and graphic sexuality. Graham’s art is simple and boxed in regular 6-panel pages, but the explicit and manic moments of sex have the characters of Dog Biscuits become more expressive as their primal urges rise to the surface.

Dog Biscuits’ biggest strength comes from its refusal to moralise, not condemning or caricaturising the main characters and allowing the audience to consider their own responses. Are relationships with large age-gaps inherently exploitative, or is it more insulting to insinuate a grown woman like Rosie can’t make up her own mind? Does Gussy recognising his own insecure jealousy absolve its manifestations? Should Hissy have a going-away party or are lockdown measures mandatory for everyone? Dog Biscuits lets the readers ponder and live through these often self-destructive choices, the actions an authentic and frequently funny expression of how people clumsily navigate the world and each other.

A core theme of Dog Biscuits is searching for forgiveness, which is different from finding it. Often characters will explode or insult one another, only to coyly return and admit what they said was tied to their own mental state. What they do next is up to them. Dog Biscuits deftly shows the complexity and dynamics of the current moment, but with enough substance that it should prove a timeless testament to the complexity of living in uncontrollable times. As if there’s any other kind.

Alex Graham (W/A) • Self-published, $30.00 + shipping

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong