In the depression-era prequel to Alan’s War, cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert deftly creates a touching family memoir, an engaging piece of social history and a fitting tribute to a deep friendship.

So you want me to tell you a little about my childhood in southern California?

With this direct, conversational approach on an otherwise blank page, Alan Cope (through his graphic intermediary, the French cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert) taps the reader on the shoulder and draws them in to the intimate story of his early life.

With this direct, conversational approach on an otherwise blank page, Alan Cope (through his graphic intermediary, the French cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert) taps the reader on the shoulder and draws them in to the intimate story of his early life.

This is the second book to have sprung from the seemingly unlikely friendship that developed in the 1990s between Guibert and Cope, an American veteran who subsequently settled in France. The first volume, published in English as Alan’s War, traced the older man’s experiences as a GI in Europe in the latter stages of the Second World War.

Now, in How the World Was: A California Childhood, Guibert returns to document his late friend’s early life in California during the years of the great depression – a time when the Golden State was a very different place to what it is today.

The opening section of the book – the only part that uses colour – depicts that change vividly, as it describes the development of the state’s historic thoroughfare, El Camino Real, from the one-lane road Alan remembers from his childhood to the huge sprawling highway we see depicted before us.

The opening section of the book – the only part that uses colour – depicts that change vividly, as it describes the development of the state’s historic thoroughfare, El Camino Real, from the one-lane road Alan remembers from his childhood to the huge sprawling highway we see depicted before us.

Once we enter the core of the book, we’re taken firmly into the dense history of Alan and his extended family. The book captures perfectly the way in which family history becomes myth. Indeed, it’s arguable that Alan’s generation represents the last hurrah of that ‘oral tradition’, where stories – with their inevitable mutation over time – were transmitted by word of mouth.

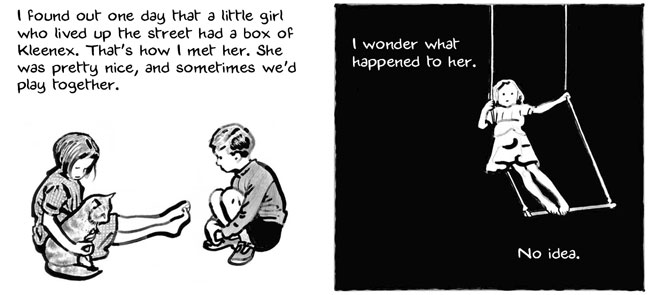

In the most uncertain of economic times, the family’s constant house moves provide an insistent rhythm of Alan landing in a new place with a new set of circumstances. The book depicts the random motion and collisions of life: those fleeting encounters and acquaintances that flare up and then fade into the darkness.

Similarly, Alan’s recollections leap around in what appears to be a fairly haphazard fashion, going from childhood capers to family history to observations of the natural world or the social history going on around him.

Crucial to the success of the book is Emmanuel Guibert’s perfectly suited art style and sense of pacing. The evocative nature of his style – a finely wrought blend of ink and wash – matches the stately narration perfectly; he’s not trying to push you through the book as quickly as possible. (And particular praise should also go to the book’s translator, Kathryn M Pulver, who maintains the wonderfully distinctive voice of Alan’s narration.)

At one point Alan says, “I’m diving down deep to tell you this story, far beneath my conscious memory”, and Guibert varies the detail of the art to match the mysterious workings of our recall. Some sequences, especially from Alan’s very early childhood, use a lot of negative space and isolated images to highlight their sketchy nature.

At one point Alan says, “I’m diving down deep to tell you this story, far beneath my conscious memory”, and Guibert varies the detail of the art to match the mysterious workings of our recall. Some sequences, especially from Alan’s very early childhood, use a lot of negative space and isolated images to highlight their sketchy nature.

There’s a slight vagueness to some of the panels that reflects the degradation of aging memory, while other locations and events that Alan remembers with greater clarity are given a much more detailed treatment.

However, Guibert’s choices step even further away from naturalism on occasion to create a more pleasing artistic effect; for instance, the Civil War experiences of Alan’s grandfather are presented as frames from an aging silent film, complete with caption cards. The image of his elderly grandfather snoozing on the verandah is then transposed onto the front cover of one of the old man’s beloved Western story magazines.

The profoundly affecting climax of How the World Was represents the book in microcosm: form, style and theme mesh perfectly as the older Alan recalls his 11-year-old self coming to a profound realisation about the nature of the world in the wake of personal tragedy (making the English-language title more poignant than the original French title of L’Enfance d’Alan).

The profoundly affecting climax of How the World Was represents the book in microcosm: form, style and theme mesh perfectly as the older Alan recalls his 11-year-old self coming to a profound realisation about the nature of the world in the wake of personal tragedy (making the English-language title more poignant than the original French title of L’Enfance d’Alan).

The heart of the book is suddenly revealed not to have been the minutiae of social history or quirky relatives, but something altogether more universal: a study of the everyday tragedies and regrets with which life weighs us all down.

However, even at this moment of epiphany, Guibert’s presentation matches perfectly Alan’s low-key narration, showing the boy going through the mundane business of getting ready for bed.

If, as William Wordsworth would have had it, “The child is the father to the man”, this simple sequence shows the outlook of the ageing Alan being encoded in his childhood self.

But then Guibert and Alan spring their best trick on us. Concluding his reminiscence, Alan highlights how there’s a strange kind of beauty in the way fate can change a person’s life.

But then Guibert and Alan spring their best trick on us. Concluding his reminiscence, Alan highlights how there’s a strange kind of beauty in the way fate can change a person’s life.

He quotes sculptor Auguste Rodin on the “rapture” that an artist – or, as Alan describes himself, an artistic person – can attain from being able to see and understand the world as it is. There’s something zen-like about Alan’s openness to the universe, shedding a fresh light on the accepting tone of his earlier recollections.

Rodin’s description is worth quoting at length:

For [the artist], everything is beautiful because he walks in the light of spiritual truth… Although at times the artist abandons himself to suffering, he experiences, even more deeply than his pain, the bitter joy of being able to comprehend and express it… When he comes face to face with the will that has decreed all those dark laws, then more than ever he rejoices in his knowledge and, sated with truth, experiences unsurpassable happiness.

It’s an astonishing, almost sublime conclusion to a book that at first glance might have looked like the unwelcome elderly chatterbox who sits next to you on the bus when you just want a snooze. As well as a moving family memoir and an engaging piece of social history, Emmanuel Guibert has delivered a fine and fitting tribute to his remarkable friend.

Emmanuel Guibert (W/A, from the memoir of Alan Cope) • First Second, $19.99, July 2014

Cool review. I would like to share this on Flipboard, but images are not traveling with the link. Are they locked somehow?