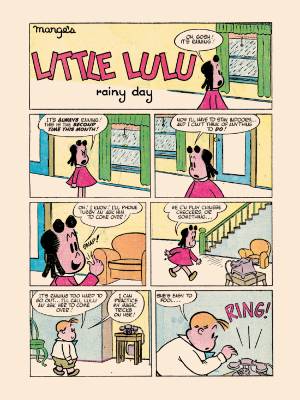

The Lulu Moppet who first appeared in February of 1935 was a far cry from the girl millions of readers have grown familiar with in the decades since. That first strip introduced her as a flower girl at a wedding, strewing banana peels down the aisle. Her famous ringlets were already in place, but she seemed slimmer, somewhat taller, and not as chubby. It makes one question how she evolved into the character we know.

The Lulu Moppet who first appeared in February of 1935 was a far cry from the girl millions of readers have grown familiar with in the decades since. That first strip introduced her as a flower girl at a wedding, strewing banana peels down the aisle. Her famous ringlets were already in place, but she seemed slimmer, somewhat taller, and not as chubby. It makes one question how she evolved into the character we know.

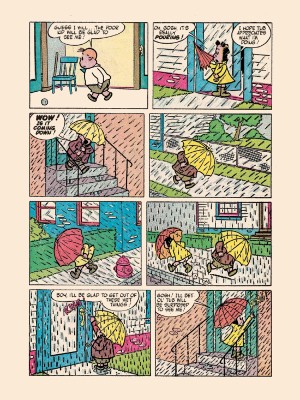

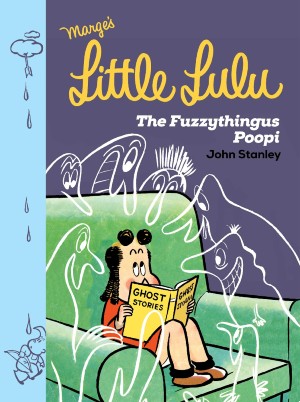

Not all comic strips age well, of course, for all kinds of reasons. This is because humour and how we perceive it tends to change as much as we do, in terms of subject matter, delivery, and obviously form. The best of Little Lulu is being republished in five volumes though — The Fuzzythingus Poopi is the second instalment after Working Girl, which appeared last year — which speaks not just about her continued relevance, but the audiences she continues to find.

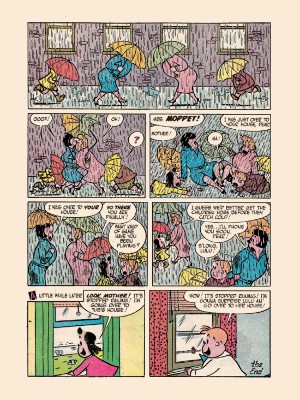

Her creator Marjorie Henderson Buell (Marge) once explained why she chose a small girl for her cartoon strip rather than a boy. She reasoned that the former could get away with stunts that would make a boy seem boorish, which goes some way towards explaining why Lulu continues to delight. She simply doesn’t do any of the things one expects of a cute little girl. She takes on her world one problem at a time and goes about fixing it all. Compared to her contemporaries, she was ahead of the curve, which is probably why icons like Margaret Atwood and Patti Smith call themselves fans.

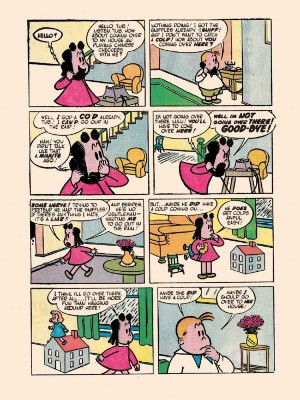

The Fuzzythingus Poopi features the work of John Stanley, who took over after Marge stopped in 1947. The title comes from a story about what is supposedly the rarest flower in existence; one that Lulu happens to find, and a crazed botanist desires at any cost. Stanley brought in more characters, made Lulu’s friend Tubby famous, and carried the series forward for the next 14 years.

There are all kinds of visual gags in these stories, but also a will of steel that flashes behind the silliness. Lulu is empowering because of the way she deals with things on her own terms and, in an introduction to this collection, American poet Eileen Myles says something pertinent: ‘Feelings are always crucial to the story. As is female triumph.

Another fascinating aspect of Little Lulu is how her relationship with Tubby evolves over the years. He starts out as a neighbour, becomes her best friend, then a powerful character in his own right, lifting the two-dimensionality of the early stories into something more profound. It may take all five volumes to depict this arc, but it deserves that treatment.

Eventually, Little Lulu’s enduring appeal can be explained by the simplest of reasons: she is funny. The first few pages of this book (The Snowball War, Little Lulu #7) pit her against a bunch of snowball-wielding boys, prompting her to form her own group. Just when one thinks she’s going to be predictable, Lulu does something out of the ordinary. Her behaviour, undeniably subversive for her time, is still refreshing.

I handed over my copy to a 10-year old and watched. She was chuckling within minutes.

John Stanley (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $34.95 CAD/$29.95 USD

(Published in September)

Review by Lindsay Pereira