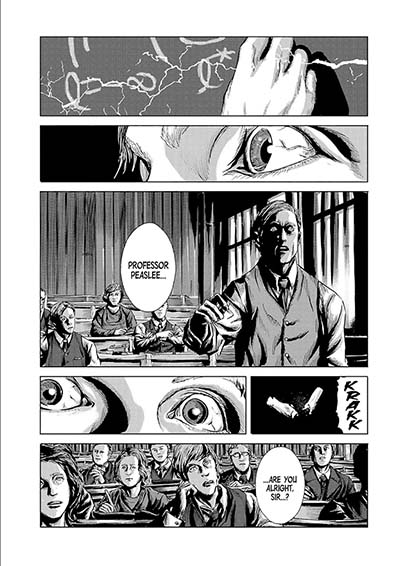

In the year 1908, Dr Nathaniel Peaslee is delivering a lecture in politics and economics at Miskatonic University, when he suddenly has an attack of some kind, and loses consciousness. He wakes up at home with his son Wingate – but the year is now 1913.

At first he can remember nothing of the intervening five years. He learns that after his attack he had a personality change, which caused his wife and other children to leave him. Immediately after the attack he struggled to speak English or control his limbs, but then a new personality took over – super-intelligent, multilingual, unsympathetic to other humans, and given to bizarre remarks and behaviour. This new version of Peaslee embarked on a series of expeditions and explorations, and also on deep research into arcane subjects, often touching on the occult.

Restored to himself, Peaslee starts to experience flashbacks. When he looks in the mirror, or down at his own body, he finds himself expecting to see something other than his own human form. He has dreams about living in this other form, in a vast city and another time, long before the emergence of man. He gradually starts to suspect – although he tries to repress the idea – that what actually happened during his five years of “absence” was a mind-swap: something else came and took control of his body, and his own personality was displaced, into the non-human form and prehistoric time he has been dreaming about.

He researches other cases of amnesia involving personality change, and he writes and publishes details of his own experiences, including his visions of the prehistoric city. As a result of these publications, he is contacted by a miner, who has found traces of an ancient city resembling Peaslee’s descriptions in the Australian outback. Peaslee sets up an expedition and travels to Australia to investigate. In the middle of the night, wandering in the desert, he comes across fragments of alien-seeming masonry. He uncovers the entrance to a tunnel, ventures inside, and finds himself back in the city of his dreams.

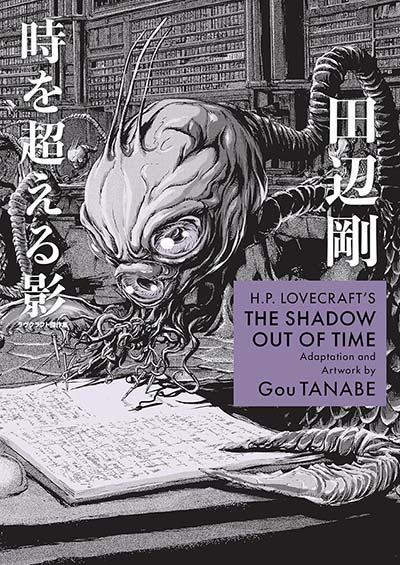

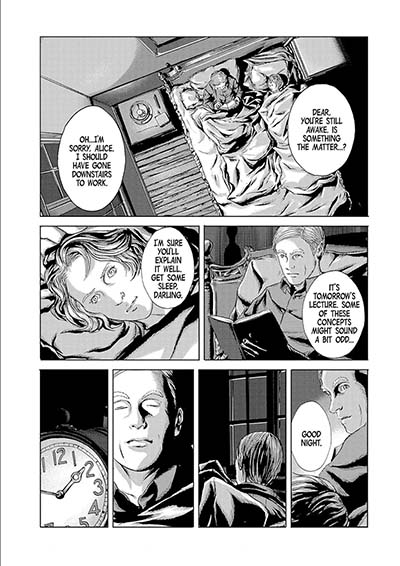

The plot summary above holds good for both H.P. Lovecraft’s original story, and Gou Tanabe’s brilliant adaptation. There are certain noteworthy differences between the two versions, however. The first of these is that Lovecraft’s original contains no dialogue. It’s almost entirely a first-person monologue, except that he does interrupt himself to transcribe the letter he received from the Australian miner. In Tanabe’s adaptation, much of the first-person narration is retained, but there is also a lot more dialogue between the characters.

This has the knock-on effect of giving secondary characters more prominence in the story. The most obvious example is Peaslee’s son Wingate. In Lovecraft’s version of the story, Peaslee tries to repress his out-of-body experiences, and to persuade himself that his visions and flashbacks can all be explained by the psychological disturbance of his amnesia, and by half-memories of the ideas he may have picked up during the bizarre researches of his “other personality”. In Tanabe’s version, on the other hand, Peaslee himself is ready to accept that a mind swap must have taken place, and it’s Wingate who tries to convince him that there must be a more rational explanation.

Another character who takes a stronger role in Tanabe’s adaptation is Professor Dyer. Dyer is a member of the expedition to Australia. However, readers familiar with Lovecraft’s other writing will know that he is also the main protagonist from At the Mountains of Madness. Lovecraft merely mentions his name in The Shadow Out of Time, but in Tanabe’s version Dyer is with Peaslee when he first stumbles across an entry to the buried city, and warns him not to investigate further: “I believe in the existence of these prehistoric civilizations you wrote about – but I also believe these things should not be disturbed!”

In At the Mountains of Madness, Dyer makes an expedition to the Antarctic, and reaches the same conclusion – that the earth still contains remnants of species which predate human beings, but that they should be left alone. The effect of bringing Dyer more to the foreground in The Shadow Out of Time is thus to link the story more closely with Lovecraft’s other writing, and with what Lovecraft aficionados call the “Cthulhu mythos”.

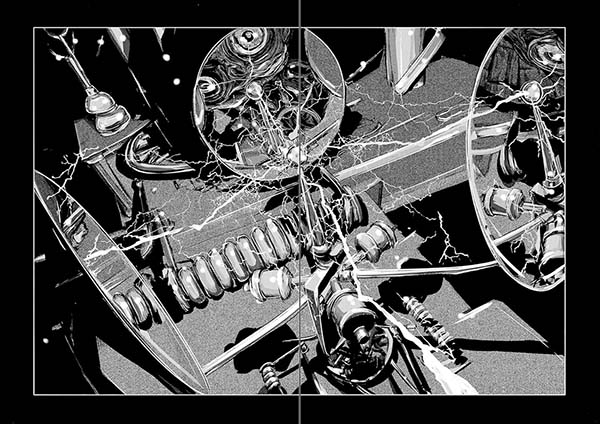

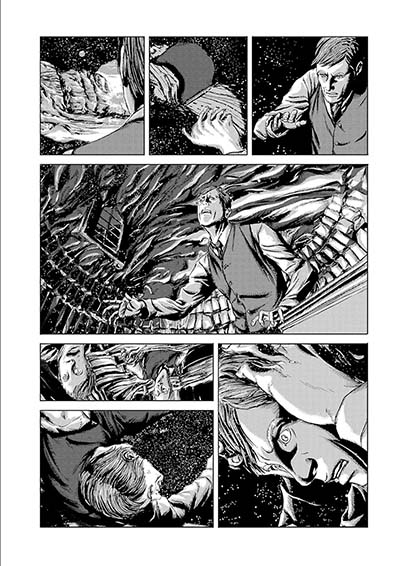

Tanabe also restructures the narrative sequence itself to some extent. In Lovecraft’s story, Peaslee describes how he either dreams or has waking visions, which take him back to the five-year period when his consciousness was transplanted into an alien body. In Tanabe’s version, these dreams and waking visions actually erupt into the story, in the form of lengthy wordless sequences. We see the conical three-eyed aliens amongst which Peaslee has been sent to dwell, and we are shown the city where they live. These wordless sequences contain some of the most striking graphics in the novel – the architecture of the alien city is especially impressive – and they pave the way for the even longer wordless sequence at the end, where we follow Peaslee into his subterranean exploration of the lost city.

Lovecraft is a particularly tricky writer to adapt into the graphic novel form, because his stories derive so many of their effects from the power of suggestion. The Shadow Out of Time is no exception. The conical three-eyed aliens who abducted Peaslee and took control of his body turn out to be only the tip of the horror iceberg – beneath their city they have imprisoned something darker and more frightening, which is never fully described. The story as a whole presents us with a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, and this layering effect, this feeling that every time we unearth one secret there is another yet more sinister secret hiding somewhere beneath, is essential to its meaning, and to Lovecraft’s artistic vision.

In the end Lovecraft doesn’t actually want to fully unwrap and explain all the secrets of his story, because part of what he wants to say is that some things are beyond human comprehension, and some things are too horrible for us to contemplate. What is left unsaid is just as important as what is fully spelt out. In the language of the graphic novel, this means is that the not-shown is just as important as the shown, and although Tanabe actually goes further than Lovecraft in his depiction of the monsters in the story, he also makes great use of obscurity and suggestion – images of black holes surrounded by stars, especially towards the end – to convey the unexplored darkness which is so important to Lovecraft and his mythos.

Gou Tanabe (W/A), Zack Davisson (T) • Dark Horse Comics, $21.99

Review by Edward Picot

Your headline has the author’s name incorrect, it is Gou, you’ve got Gau in there