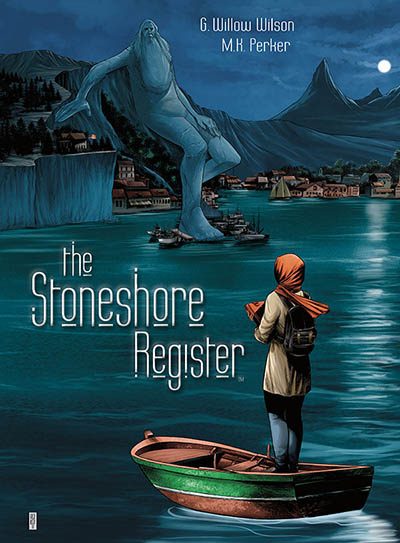

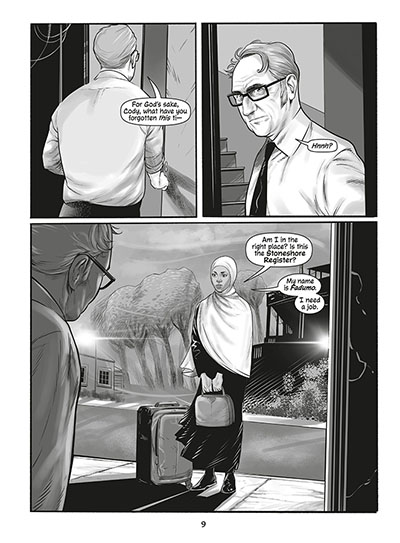

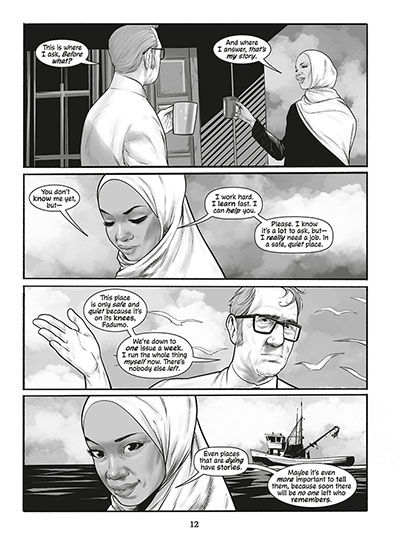

The plot of The Stoneshore Register is both simple and elusive. A refugee called Fadumo turns up looking for a job in a fishing town called Stoneshore, on the north east coast of America. “I looked for the furthest place I could find on the map”, she explains. The town is not only remote but dying – “Every year it gets a little harder for this town to keep its head above water”. Nevertheless, the proprietor of the local paper, the Stoneshore Register, offers Fadumo a job working as a journalist, in return for a stipend, and free use of an empty flat above the office.

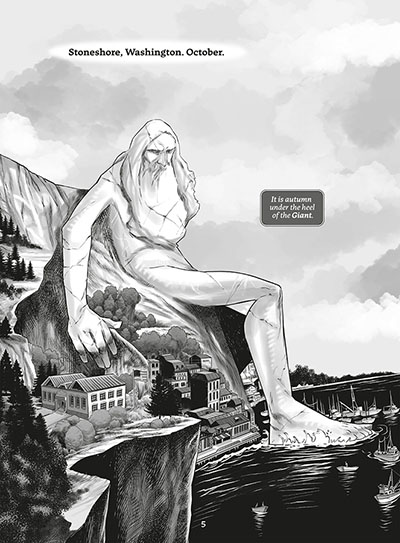

Stoneshore is overshadowed by the figure of a huge bearded giant, which has evidently been carved out of the mountain. Nobody seems to know how or when the giant was made – and even more curiously, nobody seems to be curious. When Fadumo sets out to investigate, as the basis for her first story, she is met with friendly indifference. “There’s only so many times you can wonder about something before you need to get on with your life,” a local fisherman tells her. Jonathan, the editor of the Stoneshore Register, is equally philosophical: “You still have a story… It’s just not the one you set out to tell.”

Fadumo then tries to investigate a number of secondary mysteries – did one of the local fishermen really marry a seal-woman? – do people who climb the mountain-giant in winter sometimes lose themselves in nature? – are some of the children in Stoneshore changelings, inhabited by spirits from the wilderness?

She never gets a clear-cut answer to any of these questions. Instead, as the book progresses, she builds up a picture of a town which is dying, because the environment it depends on is being depleted; but which nevertheless sustains a very close relationship with nature and its myths; and which has found a way of surviving from one year to the next by tolerating uncertainties and unanswered questions.

The Stoneshore Register deals with themes of environmentalism and man’s relationship with the natural world. In the person of Fadumo, who has fled to America from Mogadishu in Somalia, it also touches on the refugee crisis. The outlook it takes towards these questions is left-leaning, anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist – “Too may greedy wallets, not enough fish” is the way the depletion of fish stocks is summed up. It’s also tinged with hippyish mysticism about nature, and with the philosophy that we might need to let go of our intellects, and trust our feelings instead, in order to find our way to some of life’s deeper truths.

The narration can be a bit wordy at times. The style of drawing is black-and-white, and generally near-photographic in its realism. The houses, the boats, the printing machinery at the Register, the rows of bottles in the Stone Toe bar, and the faces and figures of the main characters all look as if they might be closely based on photographs. The two things which seem less photographically real are the sea, which always looks sluggish and oily, never choppy or stormy, and the stone giant itself, a massive pallid bearded figure, which apart from a few cracks is oddly devoid of detail.

This lack of detail in the stone giant may be deliberate, however, as it reflects the outlook of the book as a whole. We’re all living lives which are overshadowed by gigantic forces, and most of us can’t see those forces in any detail. We spend our time trying to get from one day to the next without thinking too much about the bigger issues.

In several obvious ways The Stoneshore Register resembles E Annie Proulx’s book The Fishing News – it’s set in an obscure town on the north-east coast of America, and it tells the story of someone who manages to land a job as a reporter, in a place where there doesn’t seem to be very much to report. But perhaps a better parallel is with Yann Martel’s book Life of Pi. Like Richard Parker, the Bengal tiger in Martel’s book, the giant in The Stoneshore Register is a figure which deliberately rebuffs our attempts to understand it. If we’re not getting the right answers, it tells us, then we might be asking the wrong questions. In the end, like Fadumo’s investigations, our intellectual inquiries can only take us so far – and then we have to make up our own minds what we want to believe.

G. Willow Wilson (W), M.K. Perker (A), Richard Bruning (L/D) • Dark Horse Comics, $24.99

Review by Edward Picot