Georgia Webber wields the full power of the comics medium to address the life-changing catastrophe of being forced into silence.

Canadian artist Georgia Webber didn’t think much of it when she started to get a sore throat in the summer of 2012. However, when the deterioration of her condition prompted her to see a doctor later in the year, she received a devastating diagnosis: she had sustained a vocal injury that would require her to stay as silent as possible for at least six months.

While that represented a shattering blow for her, it also provided the impetus for Dumb – a series of autobiographical comics that inventively address the personal and social issues raised by the sudden loss of one’s voice.

Webber has a confident, matter-of-fact cartooning style reminiscent of the late and much-missed British artist Andy Roberts. However, while her figurework is strong and appealing, she also has an imaginative, fluid approach to the form that she uses to match perfectly the tone and technical challenges of the story she wants to tell.

For all the infinite stylistic potential of comics, Webber takes on the creative constraint of using a ‘silent’ medium to describe a world defined by noise.

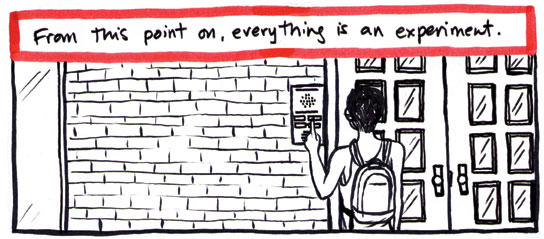

We’ve all seen attempts to depict music and song fall a bit flat on the pages of comics (although Hunt Emerson deserves a nod for the frenzied evocation of jazz in his Max Zillion strips). However, Webber succeeds by adopting a simple but effective technique; in the strictly black-and-world of her comics, she uses the colour red to represent noise.

This elegant device stretches from the simple highlighting of speech bubbles to a much more expressionistic use, as the backgrounds of noisy bars and parties become an emphatically marked ‘wall of sound’.

Webber then takes the device a step further by depicting herself branching into two Georgias: the physical, vocally impaired Georgia, in black, and her imprisoned vocal self, in red.

In a deft use of the form, #2 shows the two Georgias locked in an initially balletic conflict with each other, as along the bottom of the page, in more conventional panels, the ‘real world’ Georgia goes about trying to bend her full and active life into the new status quo that has been forced upon her.

The two avatars end up in a brutal fight as Georgia finds herself categorised as ‘disabled’ and facing financial uncertainty and a growing threat of isolation. However, reflecting a process akin to the oft-cited Kübler-Ross stages of grief, the two psychological aspects eventually reconcile and reintegrate, and Georgia, with a growing sense of determination, sticks a note on the fridge: “It’s going to be OK”.

As alluded to above, Dumb also goes beyond the practical consequences Webber faces in her daily life. Her sudden enforced silence alerts her to the wider issues of how people – women in particular – are defined by their vocality. Does silence in a woman indicate compliance and docility? Later, she’d like to enter a relationship, but is worried about ending up with someone who fetishes her quietness.

She subsequently develops a code whereby if she wears lipstick, she’s indicating to her friends that she won’t be attempting to talk. But that raises the problems of what ‘message’ she’s inadvertently sending out by wearing make-up, and what lipstick represents in the objectification of women.

(Webber addresses this in a collaged tribute to the Québécoise artist Julie Doucet, whose occasional Dirty Plotte was one of my most eagerly anticipated comic buys during the 1990s, but who tragically left comics due to an ‘overwhelming and uninviting male presence’ that left her feeling unwelcome and uncomfortable).

For all the strength of the core comics, Georgia Webber is also expanding Dumb into a much more ambitious project: “a multidisciplinary examination of voice, with many authors and subjects”.

For example, the revised print editions of the Dumb comics include prose introductions from practitioners in a number of disciplines to which the voice is central: a music writer heralds the power of a vocalist’s scream; a language-learner explores new vocal personalities; and an opera singer and vocal coach describes voice in terms of an instrument that needs to be maintained.

The Dumb series is scheduled to run to 10 issues, with #4 and #5 making their debut next month at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF) and #6 and #7 appearing later in the year (although pages from earlier issues are being posted regularly at Webber’s site).

If you’d despaired of ever finding a new autobiographical comic that had more insight and direction than the average Facebook feed, discovering the work of Georgia Webber will be like stumbling across an oasis in the desert.

Issues of Dumb, in both print and digital formats, are available from Georgia Webber’s online shop.

(Phew. I got all the way through without describing her as “an exciting voice in comics”.)

[…] I want you to check out Georgia’s work at GeorgiasDumbProject.com online. Read a great article about it on Broken Frontier online. […]