BROKEN FRONTIER AWARDS – BREAKOUT TALENT NOMINEE!

A warning to the prurient: there is precious little sex in Sex Fantasy. Instead this collection of Sophia Foster-Dimino’s self-published comics investigates the less-than-erotic little deaths that occur at every tier of intimacy. There are self-contained vignettes about affairs that end before they can begin, long-distance relationships, self-care and self-doubt, but also about individuals attempting to overcome social anxiety, the thin line that separates tenderness and cruelty, and the thoroughly unsexy side of human relationships that’s all about proving your value through being useful.

The earlier issues of Sex Fantasy cover these themes without the need for narrative. Each of the full-panel pages bears an illustration and an “I” statement. “I can carry my best friend up a hill,” “I can make eye contact when we’re speaking,” “I have perfect omelette technique.” There’s a wink at the gender binary via Rumiko Takahashi: a sequence of pages, with respective illustrations, that goes “I am a man,” “I am a woman,” and finally, “I am Ranma,” the last featuring the Ranma ½ star dunking a jug of water on their head which facilitates their swapping between male and female forms. Takahashi’s use of perspective, the roundness of her figurework and expressive eyes, is one of the stylistic touchstones here.

The earlier issues of Sex Fantasy cover these themes without the need for narrative. Each of the full-panel pages bears an illustration and an “I” statement. “I can carry my best friend up a hill,” “I can make eye contact when we’re speaking,” “I have perfect omelette technique.” There’s a wink at the gender binary via Rumiko Takahashi: a sequence of pages, with respective illustrations, that goes “I am a man,” “I am a woman,” and finally, “I am Ranma,” the last featuring the Ranma ½ star dunking a jug of water on their head which facilitates their swapping between male and female forms. Takahashi’s use of perspective, the roundness of her figurework and expressive eyes, is one of the stylistic touchstones here.

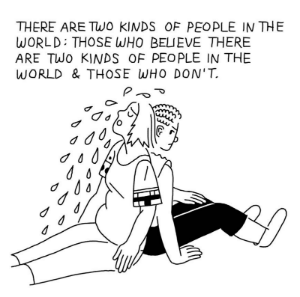

Foster-Dimino’s black-and-white cartooning is clean and semi-formalist. Bodies are constructed out of precise geometric shapes and clear lines, without much in the way of backgrounds, props or solid blacks. The deceptive simplicity of her characters, their movement and gestures, and her skill at getting across a personality, story or feeling in one image, put me in mind of the work of Laura Knetzger.

It also perhaps betrays the San Francisco-based artist’s background as a Google Doodler, contributing illustrations to the search engine’s home page, which had to get across something equally evocative in a short space of time. Some of the longer stories, where the layout barely changes between panels but for the facial expression or pose of a character, can read almost like a flip book or storyboard for animation, a field Foster-Dimino also has form in.

Something else creeps in during these charming, smaller episodes, which belies their picture book simplicity: the idea that all human relationships, whether romantic/sexual or otherwise, have a transactional element. A give-and-take. The first two issues are full of first-person statements where relationships are cemented, begun, or longed for, through the providing of evidence of being of use.

Submissiveness and dominance, the offering up of yourself, in a sexual setting, is also gestured at in these earlier episodes. A woman looks at a crack in the pavement and says “I fix the gap.” On the next page she is laying down in the crack, with people walking over her prone body. A page with the caption “I can give you medicine” has a pair of bare buttocks being injected with a syringe in the bottom right hand corner, but the person administering the injection is wearing a leather bustier and gloves instead of a medical uniform. “I like your socks,” says a smiling figure, lying face down on the ground while a woman in her underwear stands on him.

This comes to the fore in a later story where a man and woman stand in a supermarket aisle, the man encouraging the woman from off-panel to lift up her top for his gratification. She does so but demands a “treat” in recompense. When he doesn’t agree to buying her, amongst other things, champagne and truffles and caviar, she recreates a childhood tantrum, albeit expressing an adult trauma. “This is my body! This is my only body!” she wails, collapsed on her knees, as humiliated as she wants him to be from her public display.

Relationships as double-entry bookkeeping, with debits and credits and accounts that need to be balanced, is explored more starkly in a story where an anxious woman visits a more put-together instructor at a diner, who teaches her the ways of basic social interactions, like a finishing school for the conversationally maladroit. “You have to give compliments to receive compliments,” (and also, more practically, “You have to give nudes to receive nudes”) she tells her pupil.

“Some people live without trying. For others, like us, living is an acquired skill,” the instructor says. But we know that’s not entirely true. Intimacy, affection and love are more than transactional things. Saying the right thing can only get you so far, and sometimes the right thing isn’t clear. And how about when you don’t want the “right” thing?

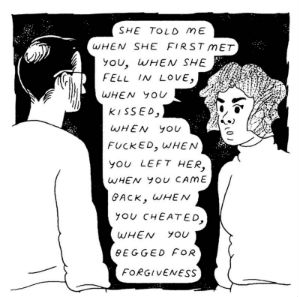

The final story in the collection finds two adults, a man and a friend of his wife, admitting their previously-hidden feelings for each other on a group holiday. Alone in a cave by the beach, they share details of fantasies they’ve had about one another. They agree to not to pursue these feelings any further. There was a transaction — the swapping of each their private fantasies — but no consummation as a result of the exchange, and so the man returns to his partner but each stares at the other from across the table, at what could have been.

Even when it settles into more conventional narratives than the more esoteric first sections, Sex Fantasy still boasts instances of pure fantasy. In one story, a couple’s hike ends with one of them turning into a bird, which looks not unlike Tezuka’s Phoenix, and flying them home. In another, a college student crosses the country to visit her internet boyfriend, the terrifying scale of the big wide world and her inexperience with visually symbolised by her miniscule, Little My-like stature. Even in these instances, the versatility of Foster-Dimino’s art and compositions, and the clarity of the ideas she expresses, makes for a coherent collection of insights.

Sophia Foster-Dimino (W/A) • Koyama Press, $18.00

Review by Tom Baker