We are plunged into the world of Brigitte Archambault’s unnamed protagonist in The Shiatsung Project without a preamble. We aren’t given any information about who she is, why she lives in the house she is trapped in, and what the purpose of her presence within its walls is. These questions remain unanswered. What we get instead is a series of illuminating insights into the nature of reality, how we can sometimes define ourselves only by relating to others, and whether technology really is the benevolent force it is often made out to be.

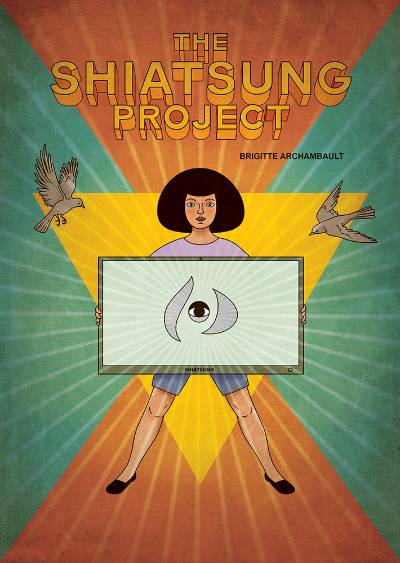

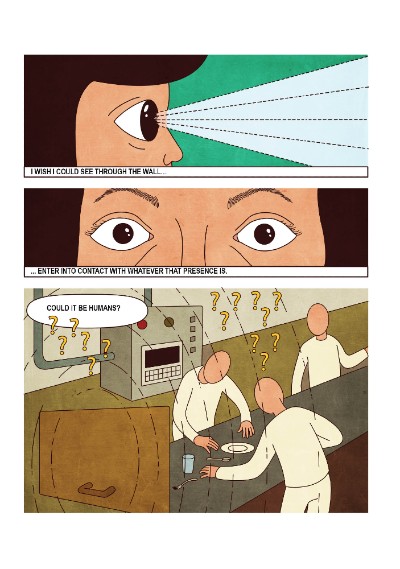

Archambault’s heroine—because there is ultimately something heroic about anyone trying to make sense of any challenging situation they find themselves in—has nothing but a television monitor for company. It is called Shiatsung, and we aren’t told if that is the name of a brand, software, or company controlling the monitor. It’s what she has always called it because she has known nothing else. At some point, she recalls stumbling upon a booklet that gives her a sense of larger forces manipulating her, but that discovery is as vague as everything else she has managed to learn. All she knows and has ever known is this house and this monitor that masquerades as a surrogate parent.

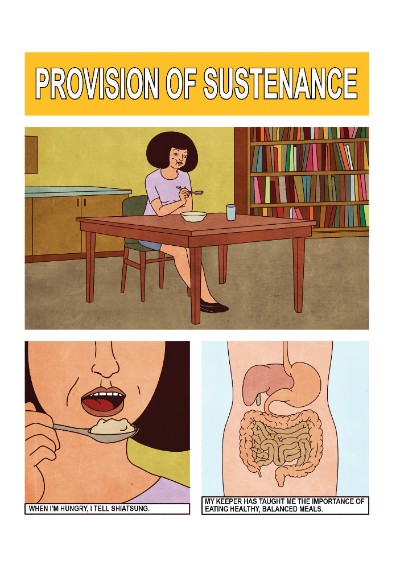

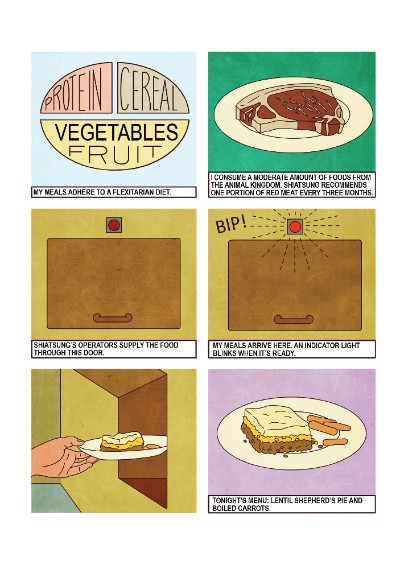

Shiatsung controls everything to do with this woman’s life, from feeding her and getting rid of her garbage to making sure she has enough toilet paper and shampoo. It asks her to choose between education and distraction, then answers her questions about the world or shows her cartoons depending upon what she chooses. When she demands pizza, there is an illusion of control because it seems as if she is deciding what she wants to consume, but it is always Shiatsung that prepares and offers her the meal. A loss of electricity quickly shows her why she is completely at the mercy of this mysterious lord and master.

There are several things Archambault does to give the reader a sense of her protagonist’s claustrophobic existence. The colour palate is small, and everything within the panels is neatly, even boringly designated, with little to break the monotony. The only things that do seem at odds are panels focusing on nature, in the form of a bird’s nest or horses copulating in the wild. There is a marked difference between her monitored life and those of the animals outside.

Eventually, it is a primal urge that allows the woman at the centre of this dystopia to change her circumstances. And yet, when one considers that this change doesn’t necessarily free her, it makes her story seem even more disturbing than it already is.

This isn’t a flawless debut. The heroine’s only human interaction is moving, but also clumsy because it seems as if Archambault wants the narrative to shift in a particular way without a plausible explanation or means for it to do so. Does her wilful act of desperate sexuality really manage to subvert the project she plays a role in? One isn’t sure. That said, this is still an extremely intriguing look at what isn’t so far from our own realities in surveillance states. We have unnamed people watching over our every move too, and what we think of as freedom of choice is often a carefully manufactured façade.

The nicest thing about Archambault’s story is how it ultimately emphasises the importance of a human connection. It is an important comment to make in a world where that seems harder to establish than at any other time in our history.

Brigitte Archambault (W/A) • Conundrum Press/BDANG, $20.00

Review by Lindsay Pereira