After yesterday’s chat about the themes and politics of his hot new series, Undertow writer Steve Orlando tells us about the unpredictability of life, the influence of Russian literature, his journey through the comics industry and Redum Anshargal biggest secret…

Do you like pulling the rug from under readers’ feet? When I read Undertow I get a bit safe and warm and then – bang! We end up somewhere else or my expectations don’t come good. Why do that? Because that’s dangerous in an industry where, apparently, readers don’t like change.

I think that’s how you create drama, and it’s what grounds stories a bit in reality – even this story with fish people. Real life doesn’t have storied endings; it has abrupt, unplanned catastrophes a lot of the time. Sometimes hero astronauts or famous social activists die in car crashes. And I think fiction can reflect that.

And it HAS worked in drama, look at Season 2, Episode 1 of House of Cards (the Netflix Version) for a prime, no-spoilers example. Look at James Robinson’s Starman, where David Knight is simply shot and killed in the first issue.

There’s even the famous Batman Black & White story – by Brian Bolland, I think – which showed that Batman will eventually meet his end not by some diabolical scheme from a supervillain but from some punk kid on the street, with a gun, who just gets lucky and shoots him in the head.

Despite our best hopes and plans, life doesn’t always go the way we want. And real drama and real fiction should be that way too. I think in some ways that’s about the maturity of a genre.

Look at Game of Thrones, a prime example of repeatedly pulling the rug out from under the audience and upending expectations, which has cracked the zeitgeist in a way that Lord of the Rings never did with its cross-media adaptation. LotR won an Oscar, but GoT broke HBO Go. People turn off football to watch it. And that comes from the base nature of the storytelling.

Things DO happen out of nowhere. Heroes die and villains can win (if there ARE just plain villains or heroes at all). This swift rug-pulling makes the story seem more relatable to the audience, no matter how fantastic the characters. Because they’re no longer living in a story, they’re living in something just a bit more like real life.

I’ve seen Dune cited as one of your influences, but I notice that your collaborator is Russian and you tweet in Russian. Does Russian literature have an influence on Undertow?

Russian lit definitely has an influence, mainly because Mikhail Bulgakov is one of my favourite writers in history. The sci-fi influences of the book lean into the 1800s, like with Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac and Jules Verne in general. But of course I am a fan and always thinking of Aleksandr Belayev’s The Amphibious Man (or, in Russian, Chelovek Amphibii).

But I think Bulgakov is the key here. His masterwork The Master and Margarita is in many ways the keystone to all my writing, and my thoughts about art in general. And his incredible way of blending folklore, drama and satire is something I only wish I could hint at achieving.

Those ideas are so infused into Undertow‘s narrative. Is it pulp? Is it adventure? Is it satire? It’s a bit of all of them. Bulgakov gave us satire that was philosophical, horrifying and darkly humorous, without being ironic or self-conscious.

This honest belief in idea is what I hope Artyom and I can achieve. Bulgakov was unafraid to take cutting jabs at his government and his own people, but with an eye on perhaps showing them the way. And he used behemoth cats and satanic carnivals to do it. We don’t have a Walpurgisnacht in Undertow, but when you meet the Amphibian, you may see we do have a bit of a barbarian version of Woland.

How did you come to work with Artyom Trakhanov? What kind of influence does he bring to Undertow?

Artyom’s main influence is his insane creativity. We met during my ongoing search for the Russian comics community, which I did not find while I lived there in Vladimir but did find while trawling the Internet and coming upon an amazing webcomic called Mad Blade by a young Siberian madman – one Mister Artyom Trakhanov.

The webcomic is all in Russian, so apparently I was one of the first comics people over in the States to read through the whole thing and immediately heap large amounts of praise upon Artyom for his unique, inventive style.

Thanks to my middling Russian skills and Artyom’s growing English, we struck up a mad comics partnership. Artyom is wonderfully dedicated to comics and art, and his wife Katya is a fantastic illustrator as well. Collaboration is just fun with this guy, and it aggregates the creativity of any story we work on.

Artyom’s influence is huge; much of the visuals and tone come from him. My design notes are almost always emotional rather than visual, noting how the creations should make other characters in the story or readers feel, the thoughts they should evoke, and then Artyom runs that through his artistic powers and creates something amazing.

We have a similar love of insane action, strange contraptions and bold pulp, and he is constantly questioning the depth of the narrative in a positive way to uncover new details and force me to be better.

What were the first comics you read? And what are your favourites (and why)?

The first comic I ever remember reading was West Coast Avengers #16, the ‘Tale of Two Kitties’ featuring Hellcat (still one of my favourites) and Tigra. It was bought at a flea market at the same time as West Coast Avengers #20, ‘The Sands of Time’. To this day it’s probably why I love Silver Centurion Iron Man the best.

My favourite comics also include The Homeless Channel by Matt Silady, just for the raw creative drive behind the art style, combining necessity with passion, and for its human, personal story. Flex Mentallo, for its dense, layered narrative and unabashed, confident strangeness and love of comics as a cultural force.

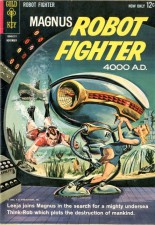

Magnus, Robot Fighter, for its ahead-of-its-time look at technology’s effect on society and classic Russ Manning art. Big Numbers, for the surprisingly grounded, human drama from an author known for anything but, and for its status as one of the great unfinished epics of comics.

Magnus, Robot Fighter, for its ahead-of-its-time look at technology’s effect on society and classic Russ Manning art. Big Numbers, for the surprisingly grounded, human drama from an author known for anything but, and for its status as one of the great unfinished epics of comics.

And Starman and The Specter, two 1990s DC releases that shaped my view of comics as a whole, with their fearless takes on comic book tropes that didn’t require a branding initiative to be bold, mature, well-researched and thought-provoking.

The Specter has especially driven me. It’s fascinating in how John Ostrander and Tom Mandrake approach a lot of the same themes, and even the same settings, as Neil Gaiman’s Sandman but from a different point of view with a different character. The way the book blends religious theory with fantasy and some good old-fashioned comics punching is just plain great.

How did you enter the comics industry?

Through an editorial! The year was 199- and I was reading a bullpen piece about Electric Blue Superman and realising slowly that my dream to be a comics artist would be stifled by my complete lack of visual artistic ability.

Flash-forward to Wizard World ’00 and I’m showing script samples at the Crossgen booth as a 14-year-old cherub and getting gleeful smirks from the other writers. But that show is where I met some of my best and most supportive peers in the industry, people like Steven T Seagle, Joe Kelly and Tony Bedard, who took the time and had the patience to help mould me over the years from a nubile yet admittedly pretty rough writer into something rounded, grounded and employable.

A special mention also has to go to Will Dennis, who I also met at Ithacon in 2000 and who has stuck with me through hackneyed pitch after absurd comics masterplan. All these guys took the time to listen and work with me to help me come into my own, which led to the ten complete pages of Undertow, plus cover, getting into the hands of the wonderful Image Comics team at NYCC 2012.

Why write a comic and not a novel? What is your favourite thing – and your least favourite thing – about comic writing?

The greatest thing about comics is the unique combination of words and pictures that fires up both sides of your brain at the same time. It’s totally unique and totally wonderful.

Comics is a tough format. You cannot always do it alone, but when you find the right collaborators you truly create something wonderful. And that’s also my favourite thing about comics. Just like when you add Byrhh to a good Mezcal (wine and spirits nerd reference!), when you find someone that really clicks with you creatively, you make each other better.

The creative team coming together, the necessary busting of balls and chops that leads to great work, is one of the best things about comics. Of course the least favourite thing is when it doesn’t work out, which isn’t always a bad thing. Sometimes people’s styles just don’t line up, and it’s not a pejorative, just a fact. That, and the wait for the next issue of Nonplayer may be the worst thing (that was the best single-issue debut in a long time).

And finally: tell me one thing about Redum Anshargal that he wouldn’t like anyone to know.

This is my favourite question! The funny thing is that there are a ton of things he wouldn’t want you to know, since his entire persona is something he constructed for the people of the Deliverer, and the only one that gets inside him is Bau Zikia. BUT, I can see you’d want more of an answer than that, and am happy to oblige!

Anshargal has always wanted a son, and he’s always wanted to take him fishing!

Huge thanks to Steve for taking the time to answer our questions, and good luck to him (and Artyom) for Undertow and their other projects. Our review of Undertow #3 is here.