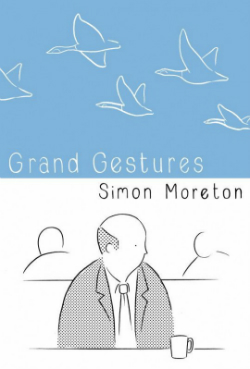

In terms of critical acclaim Simon Moreton’s autobiographical Smoo Comics series has become widely acknowledged as one of the prominent successes of self-publishing on the UK small press scene over the last few years. Since I first reviewed his comics in ‘Small Pressganged’ back in 2012 Moreton’s work has garnered attention from a number of micropublishers with Retrofit Comics publishing Grand Gestures last year and Avery Hill Publishing compiling a number of issues of Smoo in their collection Days this month. Next year his first full-length graphic novel Plans We Made will be published by Grimalkin Press in the U.S.

In terms of critical acclaim Simon Moreton’s autobiographical Smoo Comics series has become widely acknowledged as one of the prominent successes of self-publishing on the UK small press scene over the last few years. Since I first reviewed his comics in ‘Small Pressganged’ back in 2012 Moreton’s work has garnered attention from a number of micropublishers with Retrofit Comics publishing Grand Gestures last year and Avery Hill Publishing compiling a number of issues of Smoo in their collection Days this month. Next year his first full-length graphic novel Plans We Made will be published by Grimalkin Press in the U.S.

Moreton and Smoo Comics have long been a favourite of this column. I reviewed the latest issue of Smoo last summer here and just a couple of weeks back gave Days my attention here. My ‘Small Pressganged’ soundbite “Quite simply, he is one of the most important and intelligent creative voices in current UK small press comics” adorns the back cover of Days, and Moreton remains the only creator to date to feature in every ‘Small Pressganged’ 10 UK Small Press Comics You Need to Own annual round-up.

Moreton and Smoo Comics have long been a favourite of this column. I reviewed the latest issue of Smoo last summer here and just a couple of weeks back gave Days my attention here. My ‘Small Pressganged’ soundbite “Quite simply, he is one of the most important and intelligent creative voices in current UK small press comics” adorns the back cover of Days, and Moreton remains the only creator to date to feature in every ‘Small Pressganged’ 10 UK Small Press Comics You Need to Own annual round-up.

It was a pleasure indeed, then, to have the opportunity in this major interview to chat with Simon in such length about his work (as part of my ongoing ‘Small Press Spotlight on…‘ series). Read on to find out about the evolution of the trademark Smoo minimalist style, Simon’s thoughts on the DIY culture of self-publishing, comics and graphic medicine, and whether or not the current growth of the British small press scene is actually sustainable…

BROKEN FRONTIER: What were your first experiences of comics as a form? Did you discover the medium through the traditional route of “mainstream” comics?

SIMON MORETON: I read comics and cartoons growing up – my family had a collection of the little Coronet paperback editions of Peanuts that I read endlessly, there was Far Side around, and I loved Calvin and Hobbes. When I moved to the suburbs, a new friend introduced me to superhero comics – some Marvel stuff, some Image things. I did have the newsagent pull 2000 AD for me for a while, too, but that fizzled out. To be honest, I couldn’t keep up – nor wanted to – with all the different titles and storylines and the fandom and so on.

When I was 16 or 17 and started buying trade paperbacks from a secondhand bookshop in town. I bought things like a Love and Rockets collection, Sandman, some other Vertigo titles, Ghost World, that sort of thing, but had no idea what tradition they came from. At the same time, I was getting heavily into music and prose and other forms of art. Comics were just a small part of that world – and one I didn’t really mark out as distinct from any other part. In fact, I didn’t actually discover the stuff that I really liked in comics until I started making comics – and that didn’t happen until 2007, when I was about 24, which is quite late I think.

When I was 16 or 17 and started buying trade paperbacks from a secondhand bookshop in town. I bought things like a Love and Rockets collection, Sandman, some other Vertigo titles, Ghost World, that sort of thing, but had no idea what tradition they came from. At the same time, I was getting heavily into music and prose and other forms of art. Comics were just a small part of that world – and one I didn’t really mark out as distinct from any other part. In fact, I didn’t actually discover the stuff that I really liked in comics until I started making comics – and that didn’t happen until 2007, when I was about 24, which is quite late I think.

When I actually found the self-publishing world, it felt like a world I had been looking for forever. I listened to independent music and punk and DIY stuff, so I intuitively knew there was this world where you could make a mess or a noise that resisted conventional aesthetics and tastes, but I just never extended that thinking into other forms of art – I knew what zines were, for example, but not that I could just make one. It was so exciting when I started getting into zines, and that had little to do with them being comics or writing or whatever, but the community of making that went with them.

BF: How steep a learning curve was your early foray into self-publishing?

MORETON: Starting to self-publish is a mixed bag. One the one hand, you don’t know what you’re doing and that’s quiet liberating. I drew the first issue of Smoo on recycled paper that the ink bled into, at a weird size, on the kitchen table, but managed with some help from my friends to make something that looked like a zine and give it to people.

On the other hand, making something and putting it out there, especially if you’ve never done that sort of thing before, can be tough because you’re exposing yourself in a number of ways. Also, if you spend too much time agonising over the thing you are making, you never finish it, and never share it, and never improve. I think that’s a really common problem. But with self-publishing you can just put something out, and then quietly start the next thing.

Self-publishing taught me to finish things, put them out in the world, move on, start on the next thing and basically it taught me to get better.

‘Chris and Me’ from Smoo #6

BF: You’re a committed advocate of the DIY culture of self-publishing and physically your zines do have a very old school small press feel to them. Is that sense of control over product and presentation embodied in the DIY culture an integral part of your publishing philosophy?

MORETON: Well, the whole approach I take is derived from that DIY and punk culture, but I don’t think the presentation of my zines is a conscious attempt to cultivate that aesthetic – I feel it’s just the sort of work I’m making at the moment, and it’ll always bear the mark of its means of reproduction. I mean, some stuff I print off and fold and staple myself, and some things I send to a printers, and some stuff I’ve had published. That said, I don’t mind if things come out a bit scruffy or wonky, and I like people to see how things were made so they might be inspired to give it a go themselves. So maybe that aesthetic is important, after all.

In terms of how I approach making things, I see punk not necessarily as a resistance or rejection of mainstream culture, but about taking control of your own voice and connecting to people and building opportunities for change for yourself and others, even if those changes are small or quotidian. It’s not about being validated necessarily by an ‘establishment’ but imagining a different ‘establishment’. I don’t, for example, think it makes for good art to imagine your future only ever determined by traditional models of artistic success. This is why I get frustrated about the fallacy of ‘do work, be published, be a success’ that is all around us in the comic world. I see a lot of people assuming there is ‘one route to market’ and that is bullshit – graphic novel master-classes, that kind of thing. It feels like smoke and mirrors, or a PR exercise. To be clear, I’m not against publishing – that’d make me a hypocrite of the highest order – but I do think that you need to be reflexive about your own motivations, take your own path and remember that the world doesn’t owe you a living or an audience.

‘Beachcasters’ from Smoo #5

I should also point out this isn’t a ‘do what you love’ thing: I think that’s a dangerous position to adopt – I make no money from comics and I have a day job. We live in a world beset by deep inequality, precarity and austerity, and to tell people to just ‘do what they love’ would pay no heed to those challenges of gender, class, ethnicity, sexuality and so on that intersect our lives and present barriers to doing what you love. Rather, finding a form of grassroots creativity potentially offers a rejection and resistance of those social barriers, a chance to experiment with imagining things differently, and trying to effect change, however piecemeal. The challenge, the struggle, the value, is finding a way to pull those things into your life and grow from them. That might be with a publisher. That might not.

BF: Between the third and fourth issues of Smoo Comics the change in the visual presentation of your work is dramatic even if, thematically, it’s travelling similar roads. Was your move towards the minimalism we now associate with Smoo Comics a gradual one or was there some form of creative epiphany that triggered it?

MORETON: I basically burned out after Smoo #3. I was totally dissatisfied with what I was drawing, the stories I was telling. I tried something a little different with a zine called The Escapologist, but it didn’t really help – I was just fed up. In fact starting on Smoo #4 didn’t really help, either. It was originally going to be prose, and I wrote and illustrated over forty pages before I realised it was dead and lifeless.

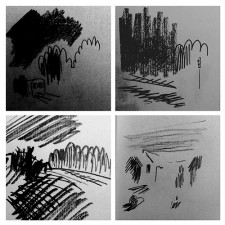

Some of Simon’s perspective changing #30DaysComics work

Out of frustration, I picked up a pencil and just scribbled, pared down the words from hundreds to a handful, and that’s what you see on the page now. The other thing that happened around this time – November 2011 – I took part in #30DaysComics, a sort-of spin-off of NaNoWriMo that Derik Badman, an American artist and critic, organised. The aim is simple: draw a comic a day for the thirty days of November. It introduced me properly to the work Oliver East and Warren Craghead and Derik and a bunch of others, got me drawing fast and differently, stopped me being so precious about what a comic was, or wasn’t, taught me that a drawing could communicate by just being a scribble, and just started to change my perspective on what I was doing more broadly.

So I went on to do Smoo #5 and Smoo #6 in 2012 with that experimentation in mind, and it was one story in Smoo #6, ‘Routines’, that marked the next turning point. I had drawn that story and was trying to fill up the white space somehow, but it just wouldn’t work. So I just left it as it was, and it was like a mini epiphany. I was pretty nervous about putting that out in the world, though.

That was the genesis of the minimalism that I put into Grand Gestures, which I think is probably the first piece of work I did that I really started to feel like I was making the kind of work I wanted to be making. That one was also my first piece of fiction – Box Brown, Retrofit head honcho who published the comic, basically said it shouldn’t be part of an ongoing series and that I should try fiction. It originally had words, but once I finished all the drawing, the words were just superfluous. Hats off to Box for being totally cool with putting out a 44-page silent comic. Weirdly, it’s also possibly the most honest and autobiographical piece of work I’ve ever done.

That was the genesis of the minimalism that I put into Grand Gestures, which I think is probably the first piece of work I did that I really started to feel like I was making the kind of work I wanted to be making. That one was also my first piece of fiction – Box Brown, Retrofit head honcho who published the comic, basically said it shouldn’t be part of an ongoing series and that I should try fiction. It originally had words, but once I finished all the drawing, the words were just superfluous. Hats off to Box for being totally cool with putting out a 44-page silent comic. Weirdly, it’s also possibly the most honest and autobiographical piece of work I’ve ever done.

Nowadays, I feel pretty confident in the voice I’m developing now; not that I feel the work is without fault – far from it – but that at least it’s honest to myself, so I can keep working at it, refining and exploring it, knowing I’m saying what I want to say, and getting better at doing so.

BF: Your minimalist layouts build a relationship between creator and audience in a way that I think is quite unique in contemporary comics; making the reader feel invested in the narrative by evoking familiar emotional sensations in them and inviting them to project their own similar experiences onto the page. As a graphic memoirist how important is it to you to not just recount personal remembrance but also to elicit comparable emotional reactions from your audience?

MORETON: Well, here’s the thing. I’m not really that interested in telling straightforward autobiographical stories because I just can’t do them. I tried for a bit, and just couldn’t make it work for me. I think I just realised that I’m more interested is trying to have a dialogue with the reader. I think that’s at the heart of zines and DIY- connecting and communicating. I think my zines reflect that – a desire to connect, to ask ‘hey, have you ever felt like this? I did too!’. The minimal style is just something that has evolved to help me be clear and immediate with that question, while still letting the reader find their own voice and place in the stories.

Pages from Grand Gestures published by Retrofit Comics

I think if boils down to the fact that I grew up quiet and shy and thoughtful, and then at some point I got more confident and, although I have my moments now, I’m pretty outgoing. But underneath my gregarious side, I do get sad, I do find it hard to communicate. So zines are a way of communicating when my silly mouth can’t do it. I guess the compulsion to entertain and make a fool of myself is the same as the compulsion I have to try and make quiet connections through my zines.

BF: Given that so much of your material is about giving an impression of a place or time rather than an exact replication of it can I ask about the way in which you recreate specific geographical locations on the page. Do you draw from reference, from life, or from memory?

MORETON: I draw entirely with soft, dark pencils these days, no ink. I tend to draw straight onto the page. For some pieces, I’ll do roughs and maybe iterate to get a panel right, and then use a light box for the final version: sometimes I just use the first take.

I almost always draw from life or from imagination. For Smoo #7, for example, I went back to the place I grew up and knew I was going to try and make a zine about it, so I drew lots of the scenes from life. As the stories took form, I then used those drawings or filled in the other bits from memory. Same with Grand Gestures – I went to lots of service stations for that.

Pages from ‘Caynham Court’ in Smoo Comics #7

I did used to draw from photo reference, but for me, that was awful. The drawing stopped being a drawing, started being a poor representation of a photo. Terrible. I do use the odd photo to jolt my memory, but I never, ever draw straight from it anymore – that made me come unstuck so many times while I was first making zines. Horrible feeling, knowing it would never be as good as the thing you are copying. Plus the thing you are doing will only ever be a drawing – it doesn’t get ‘better’ because it is more like a photo. It’s still a drawing.

I think that if people can parse stick figures, they can cope with something that doesn’t look like a photo.

BF: It’s something that is reflected more obviously in some of your shorter zines but pure drawing seems an integral part of your work. By that I mean that the emphasis on sequential art seems less important than capturing the moment in individual illustrations. Is that a fair assessment?

MORETON: My work is sequential, even if the timings or framings seem abstracted or transitions seem to take place over a long period of time, or over different spaces. They flow to create the sequence, even when they are deliberately interrupted or disjointed – that disjuncture is part of the sequence.

As for drawing, I love drawing. I’m sure I could draw things ‘better’, but why? A scribble can be as legible as a super-rendered drawing, if not more so. I reckon it’s more fun. And – to channel James Kochalka – who wants to get hung up on the ‘craft’ when you’ve got something to say? Or who wants to get hung up on ‘craft’ when a smudgy pencil line IS what you want to say?

BF: This month saw Days (reviewed here at BF), a major retrospective compilation of your work published by Avery Hill. What work can readers expect to see collected in the book?

MORETON: Days collects together Smoos 4, 5 and 6 (below), which are now out of print, and some other hard-to-find anthology work. There are also notes on all the stories contained in the book, and a short essay on me about making zines.

It documents that bit of my zine making when I stopped making the comics I thought I should make, and tried to work out how to make the ones I wanted to make. It’s definitely a document of a particular time in my life creatively, even though the stories in it cover a good 20 years of my life.

It’s come out really beautifully and I’m very grateful to Avery Hill for taking a punt on me.

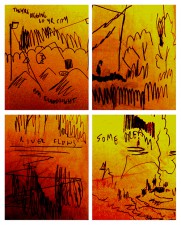

BF: Later in 2014 we will also be treated to your first full-length graphic novel from Grimalkin Press. What is the focus of this project? And did you find there were any particular challenges to creating a longer form narrative?

MORETON: The book is called Plans We Made, and should be out Spring 2015. Thematically, it revisits some of the concerns of Smoo #4, which is the place I lived before I left home for university. Essentially, it’s a teenage memoir, gathering snippets of memories and events in a roughly chronological fashion. It’s still a collection of shorter pieces and reflections, but they do have an overarching thread. Again, though, very few words, very few lines. It should be around 200 pages when done, and I think I’ve done about 60 so far.

I think keeping it interested and tonally varied is the biggest challenge: how do you sustain a reader’s interest in something silent and simple but quite long? What kind of reading experience can you create?

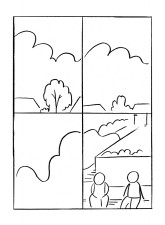

Sample pages from Moreton’s in-progress graphic novel Plans We Made from Grimalkin Press

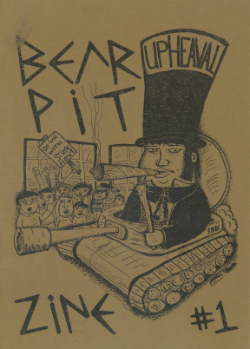

BF: Outside of your personal self-publishing endeavours you’re also involved with other small press projects. One of those is the Bear Pit anthology for Bristol-based creators. What was the genesis of that publication and what were you hoping to achieve with it?

MORETON: Bear Pit started when Nick Soucek (MisComp) and I went to Thought Bubble in 2010, and we were sat opposite Lando of Decadence Comics. Lando was living in Bristol, same as us, but none of us really knew one another. We figured we should do something about that, so we went home with the idea of starting an anthology zine that would connect together artists in Bristol and give us a collective voice. So we went home, met up, and started putting the zine together. Me and Lando really wanted to call it Trucker’s Arsehole. Or maybe it was just me who wanted to called it that. Either way, we were thankfully dissuaded from that.

The first issue (right) came out in early 2011 and when Lando moved away from Bristol, Esme Barnaville stepped in, and Es, Nick and I have been putting the zine out ever since. In fact, we’re about to launch #9, with a special perfect-bound anniversary issue 10 due out in October.

The first issue (right) came out in early 2011 and when Lando moved away from Bristol, Esme Barnaville stepped in, and Es, Nick and I have been putting the zine out ever since. In fact, we’re about to launch #9, with a special perfect-bound anniversary issue 10 due out in October.

As for the aim of Bear Pit, it was to connect together artists, of any ability, and create a network of makers – illustrators, writers, cartoonists. We also wanted to get people self-publishing – to show people how easy it could be and give people a bit of support in that first step. So we’ve had established artists and first-timers in Bear Pit, and our network is pretty expansive now. I have no idea how many people we’ve had in Bear Pit now. I should probably look it up.

The same network also gave birth to the Bristol Comic and Zine Fair which Es, Nick and I started in 2011. That’s an extension of the zine insofar as it’s about connecting artists with one another, but it’s also about growing audiences – a free event for people to come and browse and see what is being made, outside of the usual comics conventions.

BF: Your own personal struggles with mental health issues are a recurring theme in your work. Could you give us some background on the Better, Drawn website that you set up as a platform for anyone to submit comics detailing their experiences dealing with long-term illness, whether mental or physical?

MORETON: Better, Drawn started out of an idea I had in the shower one day – just give people the chance to share their stories, if they feel they can or want to. I mean, I don’t have a fixed opinion on how the relationship between mental health and making art works. I know I’ve made myself ill making comics, just as I know I’ve made myself better making them. I certainly don’t think they’re always cathartic. But I think exploring that relationship, personally or collectively, can be fruitful, and Better, Drawn is a platform for that – for people to learn, share or explore creative voices.

As for me, I’ve suffered from depression since I was a teenager, and anxiety since I was 21. I’ve had difficult times and very difficult times and totally normally times. It’s part of who I am these days, but certainly isn’t all that I am.

BF: You’re also a co-organiser of the Bristol Comic and Zine Fair. From your perspective as both a creator and an event organiser how has the small press and zine scene evolved in the years you have been involved with it? And what do you feel are the greatest challenges it faces in maintaining the growth it has seen in recent years?

MORETON: Well. I can see that the community has swelled, the diversity of work greatly improved, and people’s understanding of what can constitute ‘comics’ broadened. That’s great. At the same time, I am frustrated by how that growth has been understood and framed within ‘comics’. We say comics are for everyone, but we still charge people to come and see artists at our biggest events, or advertise comics exhibitions with the most cliché comics-as-aesthetic imagery and expect it to speak to people who don’t already self-identify as comics fans. So while I think people are putting a lot of valid effort into say saying ‘comics are culturally important’, it can still often feel like a fan culture legitimising itself, rather than genuinely engaging with the world and trying to learn and grow its artform with a new audience.

MORETON: Well. I can see that the community has swelled, the diversity of work greatly improved, and people’s understanding of what can constitute ‘comics’ broadened. That’s great. At the same time, I am frustrated by how that growth has been understood and framed within ‘comics’. We say comics are for everyone, but we still charge people to come and see artists at our biggest events, or advertise comics exhibitions with the most cliché comics-as-aesthetic imagery and expect it to speak to people who don’t already self-identify as comics fans. So while I think people are putting a lot of valid effort into say saying ‘comics are culturally important’, it can still often feel like a fan culture legitimising itself, rather than genuinely engaging with the world and trying to learn and grow its artform with a new audience.

The other thing that is happening is that the audience behind the tables at many conventions is growing faster than the audience in front of the tables, which has certainly been the experience of the organisers of Thought Bubble, and SPX in the USA over the last couple of years. The problem with that is that if half of your audience is makers, and the other half self-selecting fans, fairs will never grow fast enough to sustain that growth. And when your audience is other creators and makers, well – you’re just shifting goods and money around a closed system.

I am optimistic, though. I do think that this is already starting to change, though – Breakdown Press’ new show Safari Festival, and ELCAF, are all shows that are trying to imagine the art and its audience differently, and we hope that Bristol Comic and Zine Fair tries to be one of them, too. We’ll just have to see what happens over the next couple of years.

BF: And, finally, there’s obviously a lot of Simon Moreton work coming to us in the very near future but have you already got plans in mind post-Avery Hill and Grimalkin Press releases?

MORETON: Other than working on the big book, I’m doing a split zine with Jason Martin, a zine maker from California whose work I love. That should be out in the Autumn. I’ve got a bit of anthology work in the pipeline. I’m hoping to have Smoo #8 done this winter, and then Plans We Made ready for release next Spring.

As for 2015, I’m increasingly interested in what else I might do – prose? Collage? Poetry? Something colourful? I’ve got no idea. I think, however, it might be time for a change.

For more on the work of Simon Moreton check out his website here where you can also buy his self-published work here. Days can be purchased from the Avery Hill Publishing store here, Grand Gestures from the Retrofit Comics store here and Plans We Made will be released by Grimalkin Press in 2015.

For regular updates on all things small press follow Andy Oliver on Twitter here.

What a fascinating small press spotlight, from one of my all time favourite creators. Big thanks to you both for such an in-depth interview!

What a fascinating small press spotlight from one of my all time favourite creators. Big thanks to you both for such an in-depth interview!

Thanks Keara! Simon’s work is always worth covering!