It’s no secret that, while the profile of the graphic novel has never been higher, at the other end of comics’ demographic market sequential art for children continues to struggle to maintain a presence. With the sad demise not so long ago of The Dandy, after 75 years of publication, we were left in the UK with just The Beano in newsagents as the last bastion of original weekly comic strips for children not based on licensed properties, and The Phoenix in a more limited selection of outlets or by subscription.

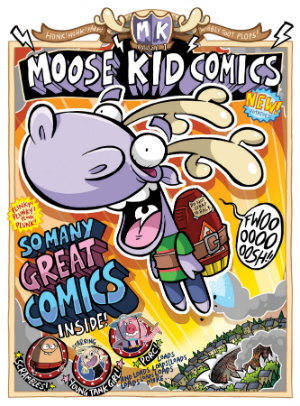

This summer, a bold, brash new project debuted designed to fill this glaring gap and prove that children’s comics are just as feasible a proposition now as they have ever been. Moose Kid Comics is the brainchild of Brit comics creator Jamie Smart whose work on material aimed at the kids’ end of the market including The DFC Library, The Dandy and The Phoenix we have reviewed a number of times at Broken Frontier in the past. Smart acknowledges the poor health of comics aimed at children – despite the quite astonishing level of talent in the UK working in this area – and the self-published Moose Kid Comics is his (for now) online attempt at proactively breathing back some life into what was once a thriving and bustling publishing arena. You can read more about the story behind this venture in my interview with Jamie here last month at Broken Frontier.

This summer, a bold, brash new project debuted designed to fill this glaring gap and prove that children’s comics are just as feasible a proposition now as they have ever been. Moose Kid Comics is the brainchild of Brit comics creator Jamie Smart whose work on material aimed at the kids’ end of the market including The DFC Library, The Dandy and The Phoenix we have reviewed a number of times at Broken Frontier in the past. Smart acknowledges the poor health of comics aimed at children – despite the quite astonishing level of talent in the UK working in this area – and the self-published Moose Kid Comics is his (for now) online attempt at proactively breathing back some life into what was once a thriving and bustling publishing arena. You can read more about the story behind this venture in my interview with Jamie here last month at Broken Frontier.

Smart has certainly built up a formidable line-up of creative talent here. Thirty-odd strips and a range of creators from all walks of UK comicdom are on show in Moose Kid Comics encompassing everyone from indie-style small pressers like Rachael Smith and Joe List to established stars of The DFC Library, The Phoenix and DC Thomson’s output like Sarah McIntyre and Gary Northfield. The comic is free to download or read online here and, to a degree, adopts that traditional style of the British humour weeklies of days gone by in the Whizzer and Chips vein of largely one-page gag-style strips. But Moose Kid Comics is no simple navel-gazing exercise in retro nostalgia. While the format may echo that of long-gone favourites the strips themselves have a contemporary sensibility and energy. This is firmly targeted at its core audience and their tastes in 2014, and is most assuredly not a misguided and anachronistic attempt to recapture the glory days of comics of fifty years ago.

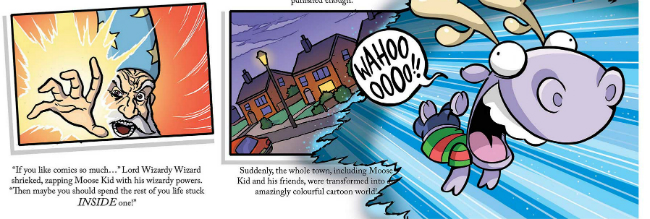

At its core there’s a rather crafty storytelling conceit to Moose Kid Comics that borders on the metafictional in construction. In a wonderfully self-indulgent strip by Smart with art by Neill Cameron and vibrant colouring from Abby Ryder, we learn that Moose Kid was once a normal boy who got on the wrong side of a society of evil wizards after inadvertently playing a part in one of their number being squashed by a runaway steamroller. In retaliation the sorcerous old geezers are not just responsible for transforming his head into that of a moose but also for trapping him within the pages of his favourite comic… a fate which our hero rather embraces!

It’s a subtly clever strip in that it doesn’t just set up the premise of the comic but also symbolically signals the ripping up of the old and the embracing of the new. It’s laid out in a very old school Rupert the Bear-style combination of images with expository text beneath them until the very last couple of pages where Moose Kid is banished within the comic and tears through the traditional design of the page with a defiant “Wahooooo!!” (above). From thereon both the Kid and the wizards pop up randomly at certain points in the comic as he journeys through its environs; the wizards, of course, playing the to-be-rebelled-against authority role that teachers, parkies, parents and the like have played in Brit humour comics for decades.

And from there we dive headfirst into an anarchic assortment of strips that mix the standard set-ups of the humour comics form with rebelliously in-yer-face irreverence. It’s always the case with anthologies that commentators can only cover a certain proportion of the characters/creators within so – and with apologies to the wealth of talent I won’t have space to mention – I will simply highlight a few of the entries here and the reasons why I particularly enjoyed them.

It’s always pleasing to be able to quickly revisit the work of a recent Broken Frontier reviewee and Tom Plant’s Gurber, featuring a strange stunted monster who lives at the bottom of Tripeton park’s duck pond, has echoes of his excellent self-published Sunshine Bay in its slapstick combination of the pedestrian and the otherworldly. Similarly, Gary Northfield is another creator who is no stranger to this site (read my Terrible Tales of the Teenytinysaurs! review here) and he provides a lively and historically none too common foray into the world of super-heroes in UK comics with the frantically paced adventures of the Pet Crusaders (right). One of this crime-fighting crew is a skateboarding goldfish in its bowl which is possibly the most splendid visual I’ve seen in any comic this year let alone just Moose Kid Comics! And Mark Stafford, that master of the grotesque and the eerie, punctuates the issue with a series of monstrously memorable parody ads that the late, great Ken Reid would have been proud of.

It’s always pleasing to be able to quickly revisit the work of a recent Broken Frontier reviewee and Tom Plant’s Gurber, featuring a strange stunted monster who lives at the bottom of Tripeton park’s duck pond, has echoes of his excellent self-published Sunshine Bay in its slapstick combination of the pedestrian and the otherworldly. Similarly, Gary Northfield is another creator who is no stranger to this site (read my Terrible Tales of the Teenytinysaurs! review here) and he provides a lively and historically none too common foray into the world of super-heroes in UK comics with the frantically paced adventures of the Pet Crusaders (right). One of this crime-fighting crew is a skateboarding goldfish in its bowl which is possibly the most splendid visual I’ve seen in any comic this year let alone just Moose Kid Comics! And Mark Stafford, that master of the grotesque and the eerie, punctuates the issue with a series of monstrously memorable parody ads that the late, great Ken Reid would have been proud of.

Nigel Auchterlounie – he of the unforgettable Spleenal from Blank Slate Books – pokes fond fun at classic characters in Airlock Homeboy and Dr. Whatsup, a science fiction take on Sherlock Holmes, while Roger Langridge is on fine, creepy form pitching his Li’l Dead Kids perfectly at its target audience with its mix of the spooky and the cute. Joe List’s gastropod gumshoe strip Doug Slugman, P.I. proves his particular brand of likeable nonsense can appeal to all ages and Stephen Waller’s Food Fighters, transporting the “War is Hell” motif onto the breakfast table is similarly good value.

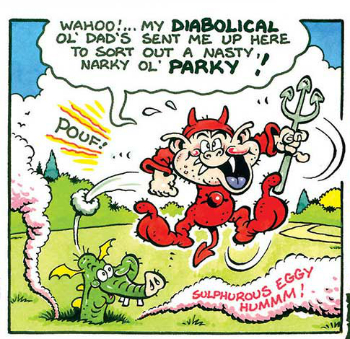

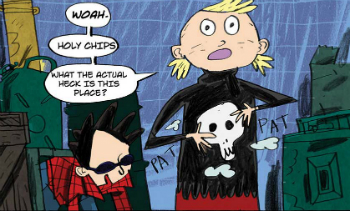

Elsewhere Chris Garbutt displays a playful humour in his one-pager starring ovoid character Scrambles and Alan Ryan gives a textbook example of how to construct a silent comic with robotic protagonists Gimbal and Chug. The legendary Tom Paterson’s demonic toddler Beelzababy will delight older readers familiar with his expansive body of IPC/DC Thomson work while up-and-coming creator Rachael Smith (House Party) provides The Amazing Seymore – seal pup magician extraordinaire – in a fleeting yet memorable example of (literally) sledgehammer wit. Perhaps the big surprise in Moose Kid Comics #1 is Young Tank Girl (below right) from the team of Alan C. Martin and Warwick Johnson Cadwell. It will certainly have a curiosity value that should drive in this cult character’s cult audience but, vitally, the strip is carefully directed at a younger readership and provides a “secret origin” of sorts for TG.

Elsewhere Chris Garbutt displays a playful humour in his one-pager starring ovoid character Scrambles and Alan Ryan gives a textbook example of how to construct a silent comic with robotic protagonists Gimbal and Chug. The legendary Tom Paterson’s demonic toddler Beelzababy will delight older readers familiar with his expansive body of IPC/DC Thomson work while up-and-coming creator Rachael Smith (House Party) provides The Amazing Seymore – seal pup magician extraordinaire – in a fleeting yet memorable example of (literally) sledgehammer wit. Perhaps the big surprise in Moose Kid Comics #1 is Young Tank Girl (below right) from the team of Alan C. Martin and Warwick Johnson Cadwell. It will certainly have a curiosity value that should drive in this cult character’s cult audience but, vitally, the strip is carefully directed at a younger readership and provides a “secret origin” of sorts for TG.

There are a few occasions where our introduction to certain otherwise intriguing features is too fleeting to really get more than a flavour of the concepts behind them at this point. Viviane Schwarz’s nonetheless fun Beasticles with its energetic evocation of childhood friendship still needs further re-enforcement of the running gag surrounding the characters’ relationship before readers can invest fully in the strip, and I loved Dan Gaynor’s Crunchwood but there’s little indication of its premise so far beyond this edition’s observations of the flawed logic of children. Controlled repetition of situations, character traits and scenarios is often the key ingredient in work of this kind so we can only hope that Moose Kid Comics has a long and healthy life because both of these strips are extremely promising in execution.

Unlike The Phoenix, Moose Kid Comics is a rapid fire volley of gags and crazy concepts rather than serial-based adventures. In that respect both publications complement each other splendidly by representing the dual roles of children’s comics of yesteryear. What Jamie Smart has achieved here is twofold: on the one hand MKC is a stunning showcase for the potential revival of the kids’ comics scene that is at the project’s heart, and on the other it also signifies a true sense of community within UK comics – of an entire group of creators pulling together to celebrate both the depth of talent we have here and the validity of the form for a specific demographic. A worthy exercise, and one that deserves both our respect and our support.

Unlike The Phoenix, Moose Kid Comics is a rapid fire volley of gags and crazy concepts rather than serial-based adventures. In that respect both publications complement each other splendidly by representing the dual roles of children’s comics of yesteryear. What Jamie Smart has achieved here is twofold: on the one hand MKC is a stunning showcase for the potential revival of the kids’ comics scene that is at the project’s heart, and on the other it also signifies a true sense of community within UK comics – of an entire group of creators pulling together to celebrate both the depth of talent we have here and the validity of the form for a specific demographic. A worthy exercise, and one that deserves both our respect and our support.

Moose Kid Comics #1 is available to read for free online here. Read our BF Moose Kid Comics interview with Jamie Smart here.

For regular updates on all things small press follow Andy Oliver on Twitter here.